AN OVERVIEW OF BATHROOM FIXTURES

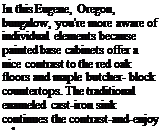

This short section provides an overview of what’s available and a few buzzwords to use when you visit a fixture showroom. Start your search on the Internet, where most major fixture and faucet makers show their wares and offer design and installation downloads. One of the most elegant and informative sites is www. kohler. com.

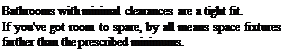

Lavatories (bathroom sinks) are available in a blizzard of colors, materials, and styles. Styles include pedestal sinks, wall-hung units (including corner sinks), and cabinet-mountedbcvaiories. Wall-hung lavs use space and budgets economically, but their pipes are exposed, and there’s no place to store supplies underneath. Pedestal sinks are typically screwed to wall framing and supported by a pedestal that hides the drainpipes. Counter-mounted lavatories are the most diverse, and they use many of mounting devices discussed earlier in this chapter for kitchen sinks. Less common are vanity top (vessel) basins, which sit wholly on top of the counter, as shown in the photo at right.

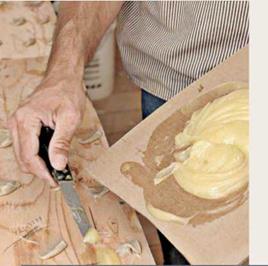

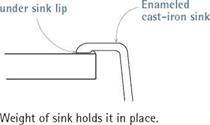

Lavatory materials should be easy to clean, stain resistant, and tough enough to withstand daily use and the occasional dropped brash or blow-dryer. The most durable lavs are enameled cast iron. Although lighter stainless-steel lavs are tough and stain resistant; their sleek, polished look is distinctively modern, so they may not look good when matched with traditional porcelain fixtures. Vitreous china (porcelain) lavs have a hard, glossy finish that’s easy to clean and durable, but it’s not as durable as enameled cast iron. Hard use can chip and crack vitreous fixtures. Spun-glass lavatories are made from soda lime glass, often vividly colored and irregularly textured. Finally, solid-surface lavatories are typically bonded to the underside of a countertop of a similar material (see "Countertops for Kitchens and Baths,” earlier in this chapter).

Important: Make sure lavs and lav faucets are compatible. Most lavatories are predrilled, with faucet holes spaced 4 in. (centerset) apart, or 8 in. to 12 in. (widespread). There are single lavs for single-hole faucets. And undermounted lavs may have no faucet holes at all; you need to drill the holes in the counter itself.

Toilets and bidets are almost always vitreous china and are distinguished primarily by their types and their flushing mechanisms. Close to 99 percent of toilets sold are of these three types: traditional two-piece units, with a separate tank and bowl; one-piece toilets; and wall-hung toilets. The other 1 percent includes composting toilets, reproductions of Victorian-era toilets with pull – chain flushing mechanisms, and so on. As noted in Chapter 12, toilet-base lengths vary from 10 in. to 14 in. (12 in. is standard), which can come in handy in a renovation when the wall behind the toilet is too close or too far.

Choosing a toilet is a tradeoff among factors such as water consumption, loudness, resistance to clogging, ease of cleaning, and cost. Washdown toilets are cheap, inclined to clog, and

banned by some codes. Reverse-trap toilets are quieter and less likely to clog than wash-downs. The quietest and most expensive models are typically siphon-jet or siphon-vortex (rim jet) toilets. Siphon toilets shoot jets of water from beneath the rim to accelerate water flow. Kohler® also offers a PowerLite™ model with an integral pump that accelerates wastes to save water and a Peacekeeper™ toilet that "solves the age-old dispute over leaving the seat up or down. . . .

To flush the toilet, the user simply closes the lid.” A Nobel Prize for that one!

Bathtubs and shower units are manufactured from a number of durable materials. And site – built tub/shower walls can be assembled from just about any water-resistant material. Bathtubs are typically enameled steel, enameled cast iron, acrylic, or fiberglass; preformed shower units are most often acrylic or fiberglass. Steel tubs are economical and fairly lightweight; set in a mortar bed, they retain heat better and aren’t as noisy if you knock against them. Cast iron has a satisfying heft, retains heat, and is intermediate in price; but it’s brutally heavy to move. For that reason, many remodelers choose enameled steel, acrylic, or fiberglass to replace an old cast-iron tub. Acrylic and fiberglass are relatively lightweight and are available in the greatest range of shapes and colors; their prices range widely, from moderate to expensive.

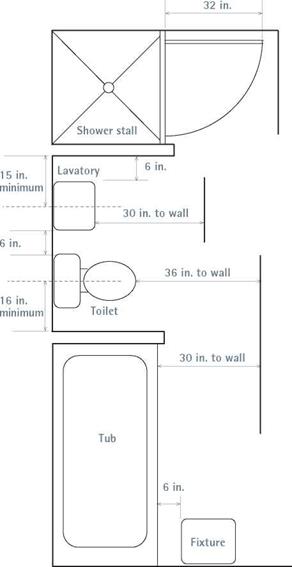

Standard tub sizes are 2 ft. 6 in. to 3 ft. wide; lengths are 4 ft. 6 in. to 5 ft. However, if space is tight, you can opt for a compact tub or replace a tub with a shower stall. Shower stalls come as compact as 32 in. sq., but that’s a real elbow knocker. Stalls 36 in. sq. or 36 in. by 42 in. are more realistic. One-piece molded tub/shower units don’t win beauty prizes, but if properly detailed and supported, they are virtually leakproof.

If you’re buying a new lav and new faucets, make sure they’re compatible. As noted earlier, lavatories often have predrilled faucet holes spaced

4 in., 8 in., or 12 in. apart. Most inexpensive to moderately priced faucets with two handles have valve stems 4 in. on center. Beyond that, the biggest considerations are faucet bodies, finishes, handle configurations, and spout lengths.

Faucet bodies will last longest if they’re brass, rather than zinc, steel, or plastic. Brass is less likely to leak because it resists corrosion and can be machined to close tolerances. Forged brass parts are smoother and less likely to leak than cast brass, which is more porous. If you spend

5 minutes operating an nonbrass faucet, it will likely feel looser than it did when you started.

|

This Moorish-inspired bath alcove has iridescent glass tiles. |

Faucet finishes are applied over faucet bodies to make them harder, more attractive, and easier to clean. The most popular finish by far is polished chrome, which is electrochemically bonded to a nickel substrate; it doesn’t corrode and won’t scratch when you scrub it with cleanser. Manufacturers can apply chrome plating to brass, zinc, steel, and even plastic. But although chrome plating protects faucet surfaces, their inner workings will still corrode and leak, if they’re inclined to.

By the way, brass-finish faucets consist of brass plating over chrome (over a solid-brass base). Brass finishes oxidize, so they should be protected with a clear epoxy coating. Alternatively, faucets finished with physical vapor deposition (PVD) coatings gleam like brass, but won’t dull or corrode.

Faucet handles are an easy choice: one handle or two. Hot on the left, cold on the right—who’d have thought you could improve on that? But there’s no denying that single-lever faucets are much easier to use. Also consider the valves inside the faucets. Ceramic-disk and brass ball – valves will outlast plastic and steel.

Spouts should have a little flare and be long and high enough to get your hands under them to lather up properly. If you’re a hand scrubber, look for a spout at least 6 in. to 8 in. long that rises a similar amount above the sink.

their own doors also makes it possible to share a bathroom during morning rush hours, yet still have privacy.

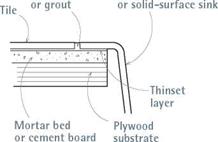

their own doors also makes it possible to share a bathroom during morning rush hours, yet still have privacy. preferable to sink rims or mounting clips that sit atop the counter. Nonporous baseboards or backsplashes allow you to swab comers with a mop or sponge without worrying about dousing walls or wood trim. Finally, you can mop bathroom floors in a flash if you have wall-hung toilets.

preferable to sink rims or mounting clips that sit atop the counter. Nonporous baseboards or backsplashes allow you to swab comers with a mop or sponge without worrying about dousing walls or wood trim. Finally, you can mop bathroom floors in a flash if you have wall-hung toilets.

In general, be skeptical of range hoods that recirculate air through a series of filters rather than venting it outside.

In general, be skeptical of range hoods that recirculate air through a series of filters rather than venting it outside.

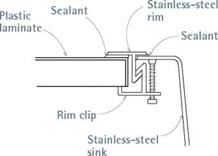

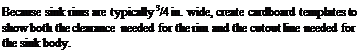

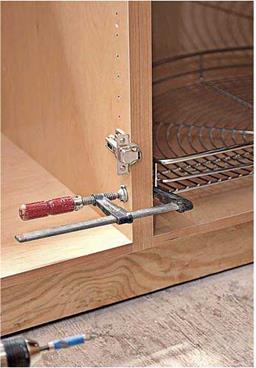

Typically, clips attach the rim to the underside of the counter; many contractors also add framing inside the sink cabinet to support the sink when it’s filled with water.

Typically, clips attach the rim to the underside of the counter; many contractors also add framing inside the sink cabinet to support the sink when it’s filled with water.

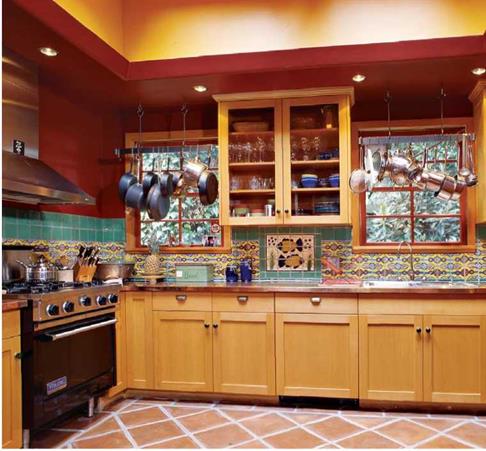

because water spots don’t show as conspicuously. A sink’s gauge (thickness) is the real differentiator. Thicker gauges (16 gauge to 18 gauge) are harder to flex and dent and are quieter to use; whereas thinner gauges (20 gauge to 22 gauge) are less expensive, less durable, and more inclined to stain. Cost: This can range widely, from $40 for a 22-gauge single-bowl

because water spots don’t show as conspicuously. A sink’s gauge (thickness) is the real differentiator. Thicker gauges (16 gauge to 18 gauge) are harder to flex and dent and are quieter to use; whereas thinner gauges (20 gauge to 22 gauge) are less expensive, less durable, and more inclined to stain. Cost: This can range widely, from $40 for a 22-gauge single-bowl

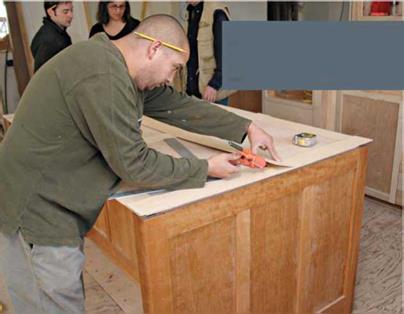

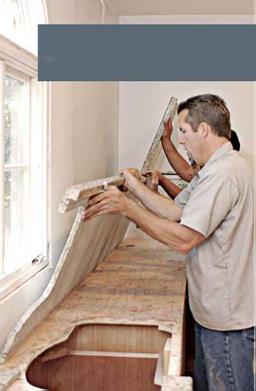

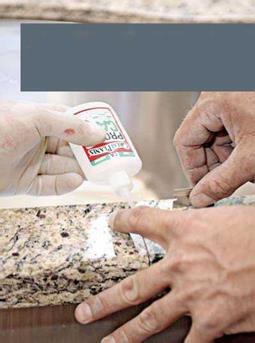

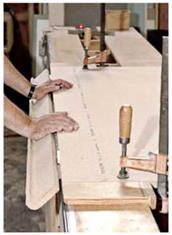

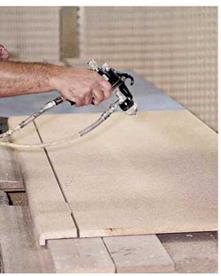

Although the photos in "Adhering Laminate Yourself,” on p. 314, were shot entirely in a custom counter shop, they depict the most critical steps for doing the job yourself. The photos in "Post-Forming a Countertop,” on p. 315, show tasks that require specialized equipment and can be done only in a shop. A custom counter shop will also trim the counter to length, trim excess laminate, and cut miter joints if the counter is L – or U-shaped.

Although the photos in "Adhering Laminate Yourself,” on p. 314, were shot entirely in a custom counter shop, they depict the most critical steps for doing the job yourself. The photos in "Post-Forming a Countertop,” on p. 315, show tasks that require specialized equipment and can be done only in a shop. A custom counter shop will also trim the counter to length, trim excess laminate, and cut miter joints if the counter is L – or U-shaped.

1111

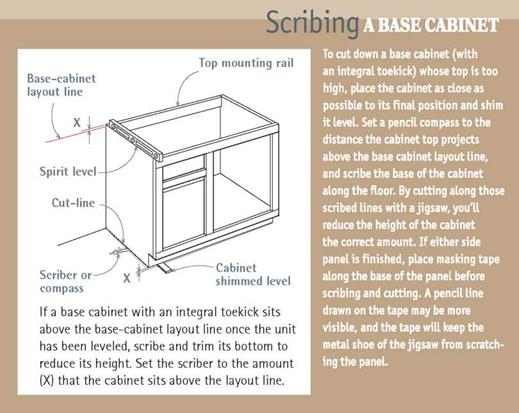

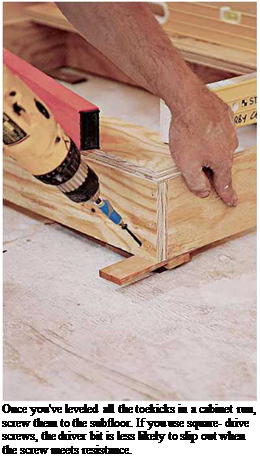

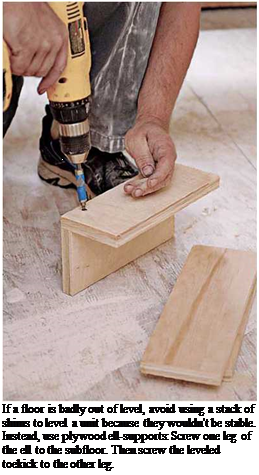

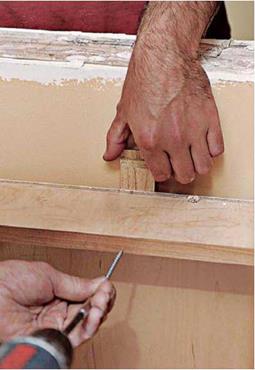

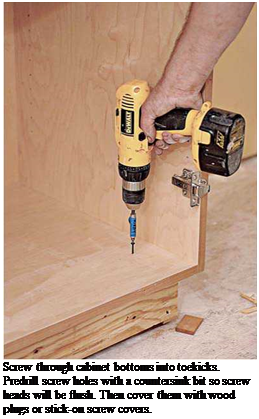

1111 Setting cabinets with integral toekicks. If

Setting cabinets with integral toekicks. If

you have a good shot at extending that level outward as you add cabinets.

you have a good shot at extending that level outward as you add cabinets.