The first step to determining your upgrade options is to learn the type and amount of insulation, if any, in your walls. Houses built before 1930 often were left uninsulated, so you will find either empty stud bays or insulation that was added later. Houses built in the ’40s, ’50s, and beyond typically were insulated, but often with thin batts that didn’t fill the wall cavity.

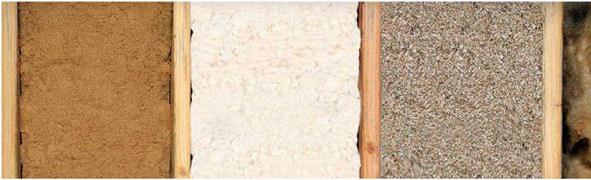

The possibilities shown here represent the most common types of early insulation, but it’s not a comprehensive list. Many of the earliest forms of insulation were driven by the local industry. If the town was home to sawmills, the surrounding houses could be insulated with sawdust. If the town was an agricultural hub, rice hulls were fairly common. What you find in your walls is limited only by the whim of the builder and the previous homeowners.

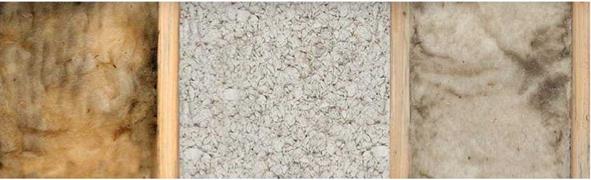

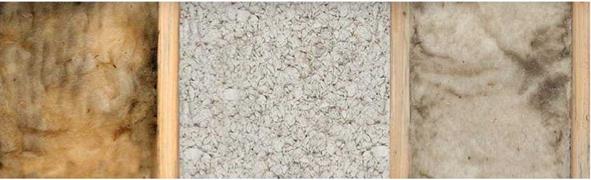

BALSAM WOOL, 1940s

What is it? "Wool" is a bit misleading because this insulation is essentially chopped balsam wood fibers.

Positive ID Although some installations may have been loose fill, this tan/brown insulation was most often packaged and installed in black-paper-faced batts. The tan fibers look similar to sawdust.

Health note Balsam wool is not a health hazard, but take care when investigating this insulation; wear a dust mask. Because the paper batts are likely to be brittle to the touch, disturbing them too much may leave holes that will decrease thermal performance.

Upgrade outlook This insulation was typically fastened to wall studs similar to fiberglass batts. Balsam wool should still yield an R-value of between R-2 and R-3 per in. if installed correctly, but the batts are likely only a couple of inches thick. Consider filling the remaining empty space in the stud cavities with blown cellulose or fiberglass. Some manufacturers of pour foam also recommend their product for this type of installation.

UREA-FORMALDEHYDE FOAM, 1950 TO 1982 (MOSTLY IN THE LATE 1970s)

What is it? Also known as UFFI, this once – popular retrofit option is a mixture of urea, formaldehyde, and a foaming agent that were combined on site and sprayed into wall cavities.

Positive ID Lightweight with brownish-gold coloring, this foam is fragile у and likely to crumble if touched (hence the smooth chunks shown at left).

Health note Because this open-cell foam was banned in 1982 and most of the off-gassing happened in the hours and days following installation, chances of elevated levels of formaldehyde are slim.

Upgrade outlook Although it’s rated at R-4.5 per in., UFFI rarely performs at this level. This foam is well known for its high rate of shrinkage and tendency to deteriorate if in contact with water, and it also crumbles if disturbed during remodeling. The result is walls that likely have large voids, but this insulation isn’t a good candidate for discreet removal. The best option here is to add rigid foam to the exterior to help to make up for the large air voids that are likely hidden in the wall.

VERMICULITE, 1925 TO 1950

What is it? This naturally occurring mineral was heated to make it expand into a lightweight, fire-retardant insulating material.

Positive ID

Brownish-pink or brownish-silver in color, these lightweight pellets were typically poured into closed wall cavities and into the voids in masonry blocks.

Health note Seventy to eighty percent of vermiculite came from a mine in Libby, Mont., that was later found to contain asbestos. The mine has been closed since 1990, but the EPA suggests treating previously installed vermiculite as if it is contaminated. If undisturbed, it’s not a health risk, but if you want to upgrade to a different type of insulation, call an asbestos-removal professional.

Upgrade outlook Vermiculite doesn’t typically settle and should still offer its original R-value of between R-2 and R-2.5 per in. This low thermal performance makes it an attractive candidate for upgrade, especially because it’s a cinch to remove: Cut a hole, and it pours right out. But the potential for asbestos contamination makes the prep work and personal protection more of a hassle, and the job more costly as a result.

If cavities are not filled to the top, consider topping them off; fiberglass, cellulose, or pour foam will work if there is access from the attic.

If cavities are not filled to the top, consider topping them off; fiberglass, cellulose, or pour foam will work if there is access from the attic.

FIBERGLASS, LATE 1930s TO PRESENT

What is it? This manmade product consists of fine strands of glass grouped together in a thick blanket.

Positive ID Most often yellow, though pink, white, blue, and green types are used. Older products were typically paper-faced batts.

Health note Official health information on fiberglass is ambiguous; the argument over whether it’s a carcinogen continues. Even if it’s not a cancer-causing material, it will make you itchy and irritate your lungs if disturbed. Be on the safe side if you plan to remove this insulation; wear gloves, long sleeves, goggles, and a respirator.

Upgrade outlook Fiberglass has a decent thermal performance of between R-3 and R-4.5 per in., but early products were typically only about 2 in. thick. Consider filling the remaining empty space in the stud cavities with blown cellulose or blown fiberglass. Some manufacturers of pour foam also recommend their product for this type of installation.

ROCK WOOL (MOSTLY IN THE 1950s)

What is it? Rock wool is a specific type of mineral wool, a by-product of the ore – smelting process.

Positive ID This fluffy, cottonlike material was typically installed as loose fill or batts.

It usually started out white or gray, but even the white version will likely be blackened or brown from decades of filtering dirt out of air flowing through the cavity.

Health note Research indicates that this is a safe material. It’s still in use today, and it’s gaining popularity among green builders.

Upgrade outlook Rock wool is fairly dense, so it’s less likely than other materials to have settled over time. If installed correctly, it should still yield a value of R-3 to R-4 per in., about the same as blown fiberglass or cellulose insulation. If anything, consider adding housewrap or a thin layer of rigid foam to the outside of the wall to air-seal the structure. If more insulation is desired, go with rigid foam.

Upgrade outlook Rock wool is fairly dense, so it’s less likely than other materials to have settled over time. If installed correctly, it should still yield a value of R-3 to R-4 per in., about the same as blown fiberglass or cellulose insulation. If anything, consider adding housewrap or a thin layer of rigid foam to the outside of the wall to air-seal the structure. If more insulation is desired, go with rigid foam.

COTTON BATTS, 1935 TO 1950

COTTON BATTS, 1935 TO 1950

What is it? Made of a naturally grown material, cotton batts are treated to be flame resistant.

Positive ID This white insulation is dense, but still fluffy.

It’s not as refined as cotton balls; instead, it’s likely to have more of a pilly, fuzzy appearance.

Although several companies manufactured cotton batts, one of the most popular seems to have been Lockport Cotton Batting. Look for a product name (Lo-K) and company logo on the batts’ paper facing.

Health note Cotton is all natural and is perfectly safe to touch, but don’t remove the batts or otherwise disturb the insulation without wearing at least a nuisance dust mask or respirator to protect your lungs. Also, cotton by nature is absorbent, so if it gets wet, it will take time to dry.

Upgrade outlook The growing popularity of green-building materials has sparked renewed interest in cotton batts. Although these modern versions of cotton batting, often referred to as "blue-jean insulation," have an R-value of R-3.5 to R-4 per in., there is some controversy over the R-value of the old versions. Some sources claim the old products perform similarly to the modern versions, and others estimate the R-value to be as low as R-0.5 per in. Considering the density of the old cotton batts, such a low R-value seems unlikely.

Upgrade outlook The growing popularity of green-building materials has sparked renewed interest in cotton batts. Although these modern versions of cotton batting, often referred to as "blue-jean insulation," have an R-value of R-3.5 to R-4 per in., there is some controversy over the R-value of the old versions. Some sources claim the old products perform similarly to the modern versions, and others estimate the R-value to be as low as R-0.5 per in. Considering the density of the old cotton batts, such a low R-value seems unlikely.

Justin Fink is a senior editor of Fine Homebuilding.

Rigid Foam Always Works

It doesn’t matter how the walls were built, what type of insulation they have now, or how many obstructions are hidden in the wall cavities: Rigid – foam panels installed over the exterior side of the walls are always an option. However, installation is not as easy as cutting the lightweight panels with a utility knife and nailing them to the framing, though that’s part of it.

Rigid foam must be applied directly to the framing or sheathing, or on top of the existing siding, then covered with new siding. In any case, you are faced with a full re-siding job and maybe a siding tearoff. Also, depending on the added thickness of the panels, windows and doors might need to be furred out, and roof rakes and eaves extended. As long as the installation is detailed carefully, though, the result is wall cavities that stay warm and dry, allowing your existing insulation to perform its best.

Panels are available in 2-ft. by 8-ft. or 4-ft. by 8-ft. sheets, and range from У2 in. to 2 in. in thickness. Vapor permeability is determined by the type of foam and the presence of a facing. Panels faced with foil or plastic are class-I vapor retarders (also called vapor barriers) and should not be used if the house has poly sheeting or an equivalent vapor retarder under the drywall. Unfaced or fiberglass-faced panels allow water vapor to pass and won’t be problematic in combination with a class-1 retarder.

EPS is unfaced, which makes it more fragile to handle but also allows the passage of water vapor. Unfaced EPS should be installed in combination with #15 felt paper or housewrap.

EXTRUDED POLYSTYRENE (XPS)

XPS falls in the middle of the three types of rigid-foam insulation in terms of cost and performance. Easy to spot by its blue, pink, or green color, XPS is slightly more expensive than EPS (50Ф per sq. ft. for 1-in. thickness) and also offers better performance (about R-5 per in.). Panels are commonly unfaced, and though water-vapor transmission slows on thicker panels, all XPS panels greater than 1 in. thick are considered class-ll vapor retarders, which allow water vapor to pass.

EXPANDED POLYSTYRENE (EPS)

These white, closed-cell panels are made from the same polystyrene beads used in disposable coffee cups. EPS is the least expensive option (45Ф per sq. ft. for 1-in. thickness) and has the lowest R-value of the group (about R-4 per in.). Some

SOURCES

www. owenscorning. com

www. polarcentral. com

www. styrofoam. com

Pour Foam Is the Most Thorough

Pour Foam Is the Most Thorough

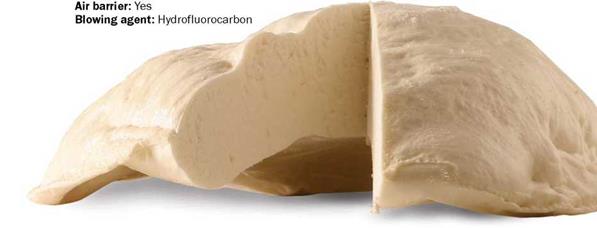

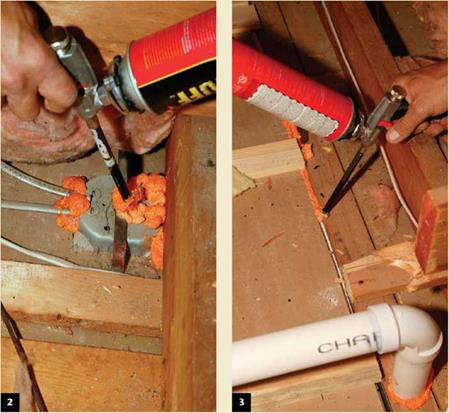

his water – or HFC – (hydrofluorocarbon) blown mixture is injected into the wall cavity from either the interior or the exterior through two or more 3/4-in.- to l-in.-dia. holes. The foam flows to the bottom of the stud cavity, where it slowly expands upward, surrounding even the most complicated plumbing and electrical obstructions, and filling every gap to create an airtight wall assembly.

Pour foam follows the path of least resistance as it expands, so the bottoms of stud cavities (in the basement or crawlspace) need to be sealed in balloon-framed houses. Old houses with siding installed directly over the studs will likely have foam squeeze-out between siding courses, which must be removed with a paint scraper once cured.

Blowouts or distortions in drywall, plaster, or siding are also possible, although this is typically not a concern if the foam is installed by trained professionals. Still, this is the reason why most pour-foam companies don’t sell directly to the public, instead relying on a network of trained installers. Tiger Foam®, on the other hand, sells disposable do-it – yourself kits to homeowners.

Rigid foam

Although there are videos on the Internet showing pour foam being injected into wall cavities that have fiberglass insulation-compressing the batts against the wallboard or sheathing-most manufacturers do not recommend this practice. The pour foam could bond to individual strands of fiberglass and tear it apart as it expands, creating voids. Tiger Foam is the exception, but the company recommends the use of a long fill tube to control the injection.

Installation from the exterior requires removal of some clapboards or shingles. Installation from the inside is easier, but requires more prep work (moving furniture, wall art, drapes, etc.). Homeowners can expect a slight odor after installation and for the day following; proper ventilation is a must.

Homeowners can plan to spend from $2 to $6 per sq. ft. of wall area for a professional installation, depending on job specifics and foam choice. Tiger Foam’s do-it-yourself kits sell for about $4 to $7 per sq. ft., depending on quantity. Open-cell foams-which are more permeable to water-vapor transmission-are about R-4 per in.; closed-cell, around R-6 per in.

SOURCES

www. demilecusa. com

www. fomo. com

www. icynene. com

www. polymaster. com

www. tigerfoam. com

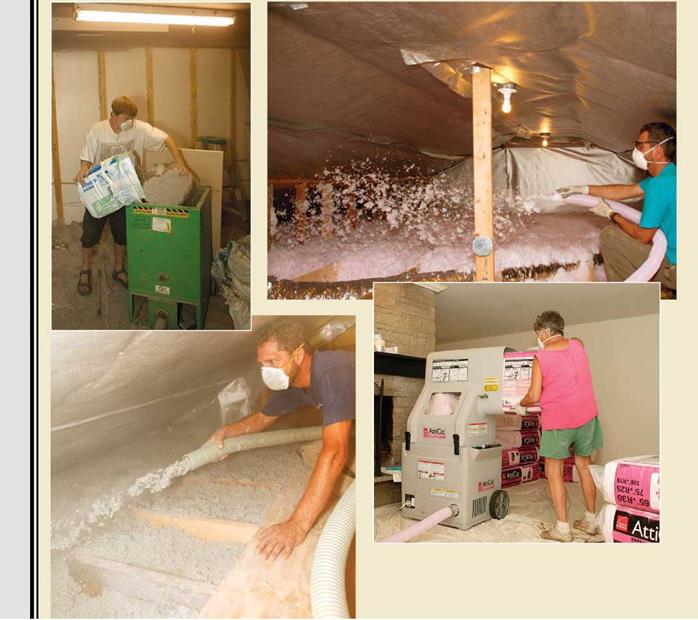

The Most Common Approach

his method begins with compressed packs of dry cellulose or fiberglass, which are dumped into the hopper of a blowing machine, where they are agitated and loosened. A 1-in.- to 2-in.-dia. hose runs from the blowing machine through a hole in the interior or exterior side of the wall and is lowered to the bottom of the stud cavity. The installation process usually involves either one hole at the top of each cavity and a long fill tube that is withdrawn as the insulation fills the space, or a “double-blow” method, where two holes are used-one about 4 ft. from the floor and a second near the top of the wall.

Both cellulose and fiberglass do a good job of surrounding typical plumbing and electrical utilities routed through the wall, but the finished density of the insulation is crucial. Cellulose that’s installed too loosely will settle and create voids in the wall, and fiberglass that’s packed too densely will not offer the performance you paid for.

Cellulose

This insulation is made from 80% post-consumer recycled newspaper and is treated with nontoxic borates to resist fire and mold. It’s a good choice because of its balance among cost, thermal performance, and environmentally friendly characteristics. Also, unlike fiberglass insulation, cellulose doesn’t rely only on its ability to trap air to stop heat flow. Cellulose can be packed tightly into a wall cavity to resist airflow-a practice called “dense-packing”- yielding an R-value of R-3 to R-4 per in.

Although blowing loose-fill cellulose into attics is a pretty straightforward process (and is touted as a good do-it-yourself project), dense-packing is more complicated. As the material is blown into the cavity, the blowing machine bogs down, letting the installer know to pull back the hose a bit. This process repeats until the wall is packed full of cellulose. Although it is possible to pack cellulose too densely, the more common problem is not packing it densely enough. Most blowing machines that are available as rentals are designed for blowing loose cellulose in an open attic. These machines aren’t powerful enough to pack cellulose into a wall cavity, and unpacked cellulose can settle and leave voids. The Cellulose Insulation Manufacturers Association (www. cellulose. org) recommends that dense-pack cellulose be installed only by trained professionals with more powerful blowing machines. Material prices are about 25Ф per sq. ft. of wall space.

Finally, if soaked with water, cellulose is likely to settle, leaving voids. Then again, if there’s liquid water in the wall cavity, voids in the insulation will be the least of your worries, and the least of your expenses.

Fiberglass

Fiberglass

Fiberglass

This loose-fill insulation is made from molten glass that is spun into loose fibers. The material is available in two forms, either as a by-product of manufacturing traditional fiberglass batts and rolls, or from “prime” fibers produced especially for blowing applications. In either case, the material is noncombustible, will not absorb water, and is inorganic, so it will not support mold growth.

Fiberglass resists heat flow by trapping pockets of air between fibers, so the insulation must be left fluffy to take advantage of the air-trapping nature of the material. The R-value (typically between R-2.5 and R-4) is dependent not only on the thickness of the wall cavity but also on the density at which the insulation is installed. For information on ensuring that the fiberglass is installed to provide the stated R-value, visit the North American Insulation Manufacturer’s Association (www. naima. org) for a free overview.

Because fiberglass doesn’t need to be blown to such high densities, it’s a more user-friendly installation for nonprofessionals. On the other hand, loose fiberglass is not as readily available as cellulose, which is often a stock item at home-improvement centers. Finally, fiberglass advocates contend that their product won’t absorb water and that cellulose will—^though fiberglass will still sag if it becomes wet. Material prices are about 45Ф per sq. ft. of wall space.

SOURCES

www. certainteed. com

www. greenfiber. com

www. johnsmanvllle. com

www. knaufusa. com

www. owenscorning. com

If cavities are not filled to the top, consider topping them off; fiberglass, cellulose, or pour foam will work if there is access from the attic.

If cavities are not filled to the top, consider topping them off; fiberglass, cellulose, or pour foam will work if there is access from the attic.

Upgrade outlook Rock wool is fairly dense, so it’s less likely than other materials to have settled over time. If installed correctly, it should still yield a value of R-3 to R-4 per in., about the same as blown fiberglass or cellulose insulation. If anything, consider adding housewrap or a thin layer of rigid foam to the outside of the wall to air-seal the structure. If more insulation is desired, go with rigid foam.

Upgrade outlook Rock wool is fairly dense, so it’s less likely than other materials to have settled over time. If installed correctly, it should still yield a value of R-3 to R-4 per in., about the same as blown fiberglass or cellulose insulation. If anything, consider adding housewrap or a thin layer of rigid foam to the outside of the wall to air-seal the structure. If more insulation is desired, go with rigid foam.

COTTON BATTS, 1935 TO 1950

COTTON BATTS, 1935 TO 1950

Pour Foam Is the Most Thorough

Pour Foam Is the Most Thorough

Fiberglass

Fiberglass

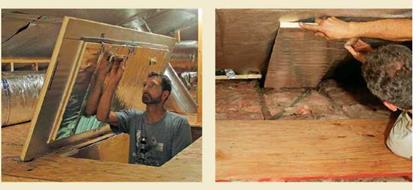

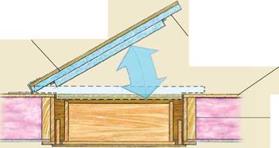

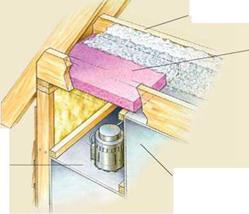

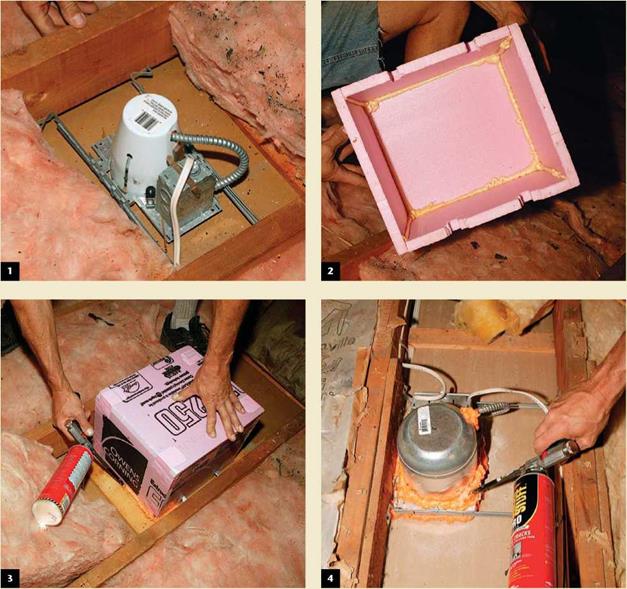

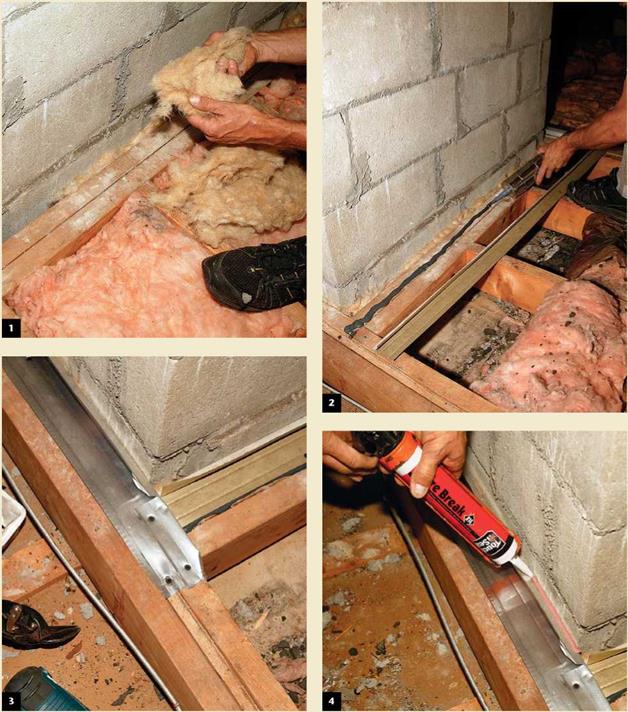

The attic access is a big leak that can be fixed quickly: Build or buy an insulated cover for the access bulkhead. The key is to provide a rim to connect to the sealing cover. The rim can be made from strips of sheathing, framing lumber, or rigid foam; then the cover sits on top or fits around the rim. On this job, I added a deck of leftover 1/2-in. plywood and OSB after the insulation was added.

The attic access is a big leak that can be fixed quickly: Build or buy an insulated cover for the access bulkhead. The key is to provide a rim to connect to the sealing cover. The rim can be made from strips of sheathing, framing lumber, or rigid foam; then the cover sits on top or fits around the rim. On this job, I added a deck of leftover 1/2-in. plywood and OSB after the insulation was added.

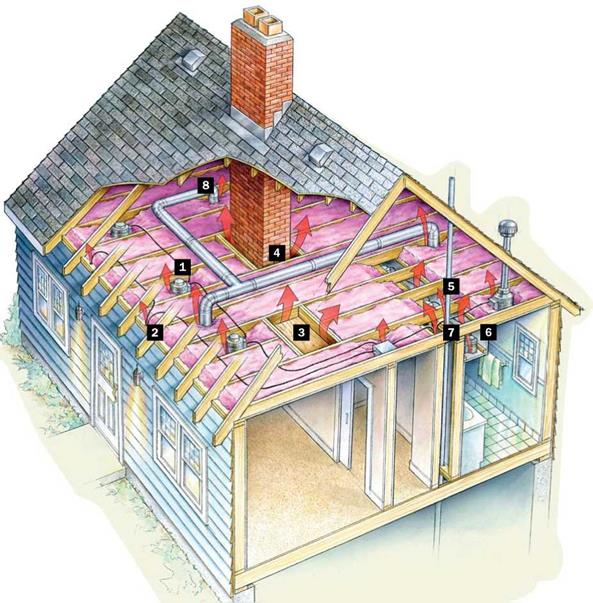

Potential Air Leaks in the Attic

Potential Air Leaks in the Attic