Retrofits

■ BY DANIEL S. MORRISON

![]()

|

F |

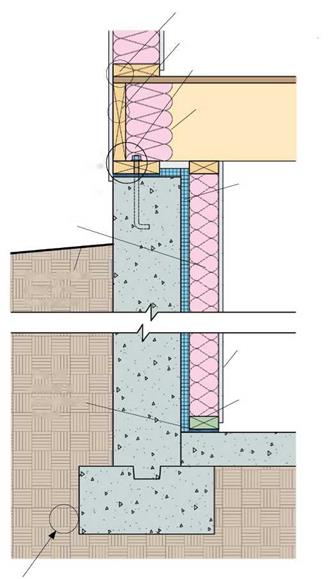

inished basements are a great way to add living space to a house without adding on. You often can add almost as much living space as the main floor offers. Before thinking about flooring choices and paint colors, though, think about the basics. Moisture, insulation, and air infiltration must be tackled before any finish materials are installed. In new construction, these issues are addressed from the outside before the basement is backfilled. Retrofits mean that you have to work from the inside. In either case, it is important to consider the climate before work begins.

Because basements are mostly buried in the ground, they are sometimes wet, are usually damp, and are seldom dry. Rarely do old houses have perimeter-drainage systems, insulation, or capillary breaks. When converting a basement to living space, the basement must manage moisture better than it did before the insulating and air-sealing, because

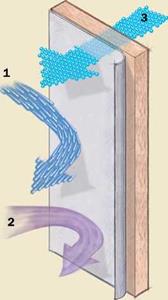

a tighter basement is less able 2 3: R-5 to dry out when it becomes wet.

You can use grading to manage bulk groundwater on the outside, but foundations also have to disrupt capillarity. Water in the soil can and will wick up to the roof framing if you let it. Capillary breaks such as brush-on damp-proofing, sill sealer, and rigid insulation block this process.

Air-Sealing Saves Energy and Stops Moisture

The connection between concrete foundations and wood framing is almost always

Insulation Amount Depends on Location

Insulation Amount Depends on Location

The International Residential Code (IRC) specifies particular R-values for each climate zone; how you get there is up to you.

|

|

|

For very cold climates, you may need to add extra thick rigid insulation or fill the stud cavities. Don’t, however, treat a below-grade wall like a regular wall. Expect bulk-water problems, and choose insulation that can handle it. Never include a plastic vapor barrier when insulating a basement wall, because it will trap moisture.

You can’t count on a footing drain to exist (or work properly) in an old house, so use grading to push away bulk water.

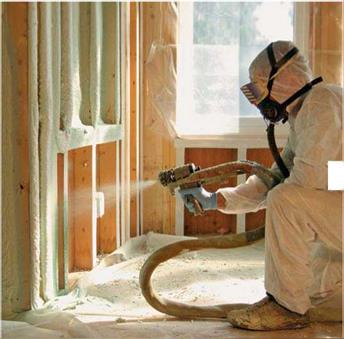

leaky because wood is often warped and concrete is rarely flat. Air leaks waste energy and cause moisture problems. Most basement air leaks occur between the top of the concrete wall and the bottom of the subfloor, where there are many joints and con

nections. The easiest way to seal and insulate the rim-joist area is with spray foam, but blocks of rigid foam sealed in place can work well, too.

Which Rigid Insulation Should I Use?

Expanded polystyrene

The least-expensive choice,

EPS is manufactured in different densities. EPS (typically white in color) is not as strong as XPS, and it’s susceptible to crumbling at the edges. EPS is the most vapor-permeable type of rigid foam.

R-value: About 4 per in.

Perm rating: 2.0 to 5.8 for 1 in., depending on density

Extruded polystyrene

Because of its high strength and low permeance, XPS (often blue or pink in color) is the most commonly used type of rigid foam for basement walls R-value: About 5.0 per in.

Perm rating: 0.4 to 1.6 for 1 in., depending on density

Polyisocyanurate

Polyiso has a higher R-value per inch than EPS or XPS. Many building officials allow foil-faced polyiso to be installed in basements without any protective drywall, making polyiso the preferred foam for basements without stud walls.

R-value: Up to 6.5 per in.

Perm rating: 0.03 for 1 in.

(with foil facing)

Mineral wool

Although many energy experts advise against using fibrous materials to insulate basement walls, some builders may want to consider using mineral-wool batts because they are less susceptible to water damage. Manufacturers include Thermafiber® and Roxul®. r-value: 3.7 per in.

Perm rating: Hasn’t been tested, but highly permeable

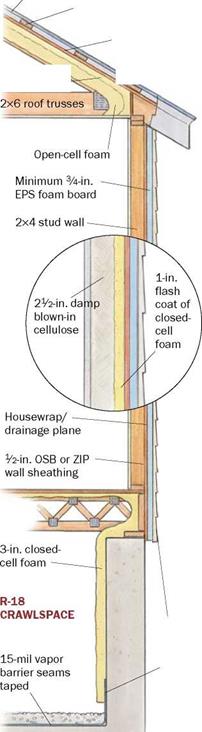

The benefits of adding a layer of rigid-foam insulation to the exterior of walls and roofs are twofold. First, the foam will increase thermal performance by adding R-value and minimizing thermal bridging. Second, the foam will keep the sheathing warm, so moisture passing through the wall or roof will find no cold surfaces for condensation to occur. For this reason, the roof does not need to be vented. That’s why exterior roof foam makes a lot of sense on difficult-to-vent hipped roofs or on roofs with multiple dormers.

The benefits of adding a layer of rigid-foam insulation to the exterior of walls and roofs are twofold. First, the foam will increase thermal performance by adding R-value and minimizing thermal bridging. Second, the foam will keep the sheathing warm, so moisture passing through the wall or roof will find no cold surfaces for condensation to occur. For this reason, the roof does not need to be vented. That’s why exterior roof foam makes a lot of sense on difficult-to-vent hipped roofs or on roofs with multiple dormers.

It never ceases to amaze me how many builders omit seam tape from housewrap installations. Although proper lapping is enough to create a watershed, all seams must be sealed to stop air infiltration. Taping the seams also helps to preserve the housewrap’s integrity throughout construction and makes the membrane less likely to catch the wind and tear.

It never ceases to amaze me how many builders omit seam tape from housewrap installations. Although proper lapping is enough to create a watershed, all seams must be sealed to stop air infiltration. Taping the seams also helps to preserve the housewrap’s integrity throughout construction and makes the membrane less likely to catch the wind and tear.

Seam tape also provides a means to repair cuts, but every cut or penetration should always be treated like a horizontal or vertical seam. Seam tape is never used to make up for improper lapping. In fact, assume that the tape adhesive will fail eventually, allowing water to penetrate the drainage plane and wet the framing. In contrast, a proper lap can last forever.

Seam tape also provides a means to repair cuts, but every cut or penetration should always be treated like a horizontal or vertical seam. Seam tape is never used to make up for improper lapping. In fact, assume that the tape adhesive will fail eventually, allowing water to penetrate the drainage plane and wet the framing. In contrast, a proper lap can last forever. Several manufacturers have started combining the water-shedding benefits of rain-screen-wall construction with the ease of installation and the added benefits found in typical housewrap, creating a separate category sometimes referred to as “drainscreen.”

Several manufacturers have started combining the water-shedding benefits of rain-screen-wall construction with the ease of installation and the added benefits found in typical housewrap, creating a separate category sometimes referred to as “drainscreen.”

Also, the compatible sealing tapes and accessories make housewrap a superior air barrier compared to felt paper.

Also, the compatible sealing tapes and accessories make housewrap a superior air barrier compared to felt paper.

increase comfort by reducing air infiltration and potential drafts.

increase comfort by reducing air infiltration and potential drafts.