All You Need to Know about Spray Foam

■ BY ROB YAGID

|

I |

recently spent a day pulling wire with a friend who’s an electrician in New York. Late in the afternoon, our conversation turned to a client and friend of his who was seeking advice about insulating her new home. The topic caught the interest of some other guys on site, most from different trades, who gathered around and offered their opinions on which material she should use. After a brief debate, everyone seemed confident that spray foam would yield the best performance. That was until I threw out the question, "Which type?" Sure, they all knew there were two types of spray polyurethane foam, open cell and closed cell, but no one knew enough about them to step up and defend the use of one over the other. The truth is, neither did I.

Spray polyurethane-foam manufacturers have a relatively easy job when it comes to marketing their products because of one key statistic. According to the U. S. Department of Energy, 30% or more of a home’s heating and cooling costs are attributed to air leakage. Spray polyurethane foam, or spray foam as it’s most often called, is an effective air

barrier and significantly reduces energy loss. Combined with a higher R-value than most other forms of insulation, it’s no wonder spray foam is often relied on to help make houses ultraefficient. Choosing to insulate your home with spray foam doesn’t guarantee that it’ll perform to its full potential. Different climates, construction practices, and wall and roof assemblies benefit from different types of foam. The installation of foam at specific thicknesses is critical when you’re trying to get the most performance for the money.

It Won’t Settle, and It Doesn’t OffGas Toxic Chemicals

Because of the urea-formaldehyde foam used to insulate homes in the 1970s, which could degrade and off-gas unsafe formaldehyde, spray foam is often perceived as being unhealthful and poorly performing. Installers that look as if they’re outfitted to survive a

|

|

nuclear catastrophe perpetuate the misconception that spray foam is toxic.

The fact is that when it’s installed properly, spray foam is more physically stable than the studs and sheathing it’s adhered to. The oxygen-supplied respirators and head – to-toe protective suits installers wear are necessary only to keep the chemicals that make up spray foam out of their lungs and off their skin during installation.

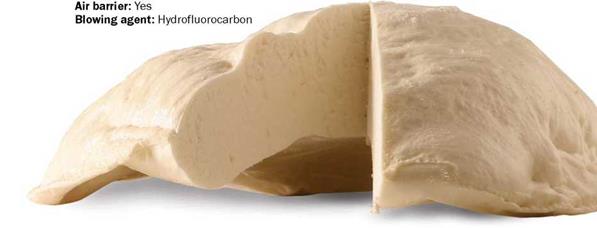

The blowing agent, a gas that expands the foam’s cells to give it volume, receives a lot of scrutiny. Over time, from three months to a year, a portion of the blowing agent in closed-cell foam evaporates into the air. Prior to 2003, chlorofluorocarbon and hydrochlorofluorocarbon blowing agents were in widespread use. These gases are damaging to the atmosphere. The U. S. Environmental Protection Agency has banned the use of those chemicals and recognized the current hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) blowing agent as a safe alternative.

Open-cell foam, which uses water as its blowing agent, emits carbon dioxide as it expands. But manufacturers claim that the amount of carbon dioxide released from the foam has a limited impact on the environment. The Spray Polyurethane Foam Alliance is currently testing this issue.

Leave a reply