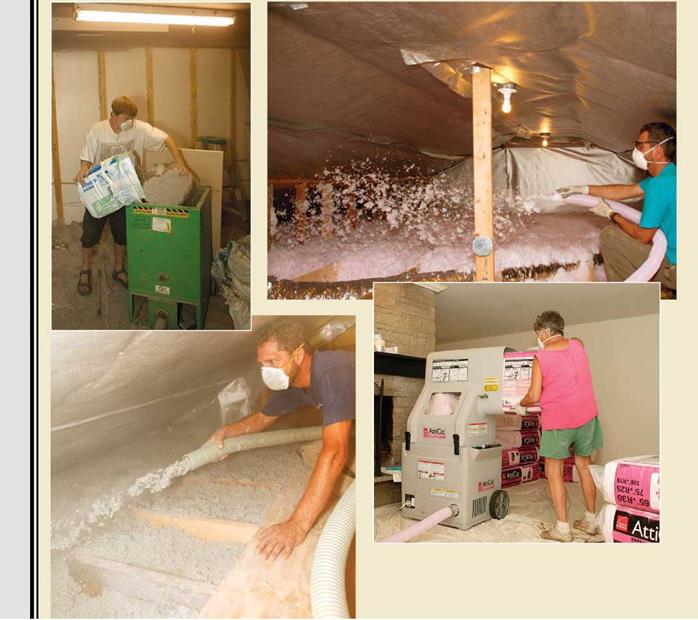

Blowing Insulation Is a Team Effort

|

A |

division of labor keeps insulation flowing. One person handles the hose, and the other feeds the blowing machine. The most critical job is at the machine (see the top left photo below and the bottom right photo), where the steady rate of insulation flow is controlled by the operator. At the other end of the hose, it’s best to start at the farthest point and work back to the attic access. A slight upward hose angle helps to spread the insulation more evenly.

Fiberglass made easier

Owens Corning® (www. owenscorning. com) has introduced AttiCat®, a rental system that processes and distributes bales of fiberglass. The packaging is stripped as the bale is pushed into the hopper. Then the machine agitates the fiberglass and blows it out through the hose. The blowing fiberglass (top right photo below) is not as dusty as cellulose.

settle more than fiberglass. Of the two materials, cellulose is generally more available to homeowners; both can be installed with the same basic techniques. A two-person crew is the absolute minimum. The machines used to blow in insulation vary in power and features, but rental machines are typically the most basic.

Pick a blower location as close to the attic access as possible. Cellulose and blowing fiberglass are messy to handle, so the loading area will be covered quickly. I prefer to set up outside, but a garage is an ideal place to stage the bales and blower when the weather doesn’t cooperate. I lay down a large, clean tarp and place the machine in the middle with the bales close by. Insulation that falls onto the tarp is easy to gather up and reload. Don’t let any debris get mixed into fallen insulation. Nails and sticks can jam the blower or plug the hose.

Route the delivery hose through the shortest, straightest distance to the attic.

Runs of 50 ft. or less are ideal. Runs longer than 100 ft. or runs with a lot of bends reduce airflow and can lead to a plugged hose.

All blowing machines have an agitator that breaks up the insulation bales and a blower that drives air and insulation through a hose. The person feeding the machine breaks up the bales and drops them through a protective grate on top of a hopper. It takes a little practice to know how fast and how full to feed the machine, especially when using a basic blower. Fill too fast, and you run the risk of slowing the flow through the delivery hose. After a little practice, the loader understands the sounds the blower makes and can adjust loading speed for optimal delivery.

The insulation dispenser handles the hose and works from the far ends of the attic toward the access hole. Good lighting is a must. If hard-wired attic lighting isn’t enough, run a string of work lights or wear a high-powered headlamp. Discharge the hose at a slight angle upward, and let the insulation fall into place. This helps it to spread more evenly. Shooting the hose directly at

the ceiling causes the insulation to mound up. If high spots occur, use a long stick or broom to even them off. Although high spots aren’t really a problem, low spots don’t perform as well.

Once insulation covers the ceiling joists, there’s little way to know the depth of the insulation. Insulation distributors sell paper gauges marked in inches that you staple to rafters or ceiling joists. I make gauges by cutting 11/2-in.-wide cardboard strips about 1 in. to 2 in. longer than the target depth; I draw a line across each strip at the final insulation grade. Expecting the insulation to settle 1 in. or 2 in. over time, I mark the strips at 14 in. and staple them to the sides of the ceiling joists every 6 ft.

Mike Guertin (www. mikeguertin. com) is a builder, remodeling contractor, and writer in East Greenwich, R. I.

Leave a reply