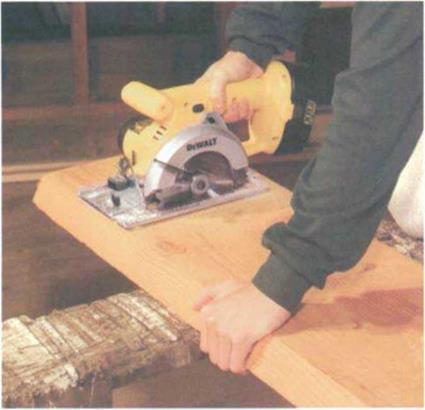

A cut across the grain is called a crosscut. To make one, first scribe a cut line on the stock using a square to draw the line straight. Make sure that the stock is adequately supported either by sawhorses or by 2x blocks placed on the floor so that the cutoff can fall free. Then place the saw base on the stock with the blade about 1 in. from the edge of the wood and align the blade with the cut line. Hold the saw with both hands, pull the switch, and slowly push the blade into the wood, following the cut line. Going slowly and cutting straight helps prevent kickback (for more on preventing kickbacks, see the sidebar on p. 43).

To make a square cut without scribing a cut line in 2x4s and other narrow stock, align the front edge of the saw base parallel to the edge of the stock and make the cut. Try this a few times on scrap, checking each cut with a square to see how you’re doing.

|

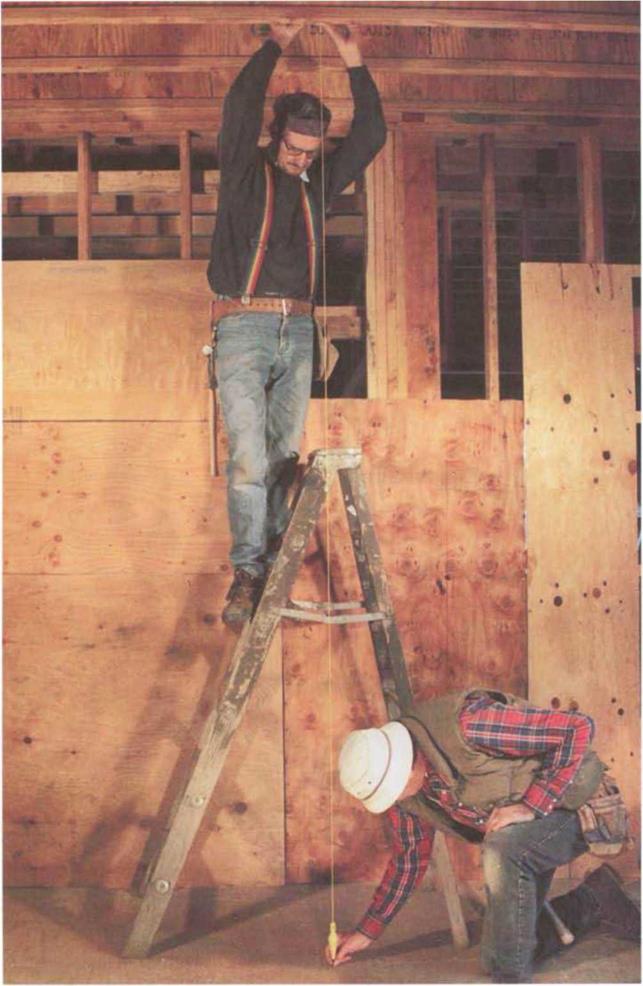

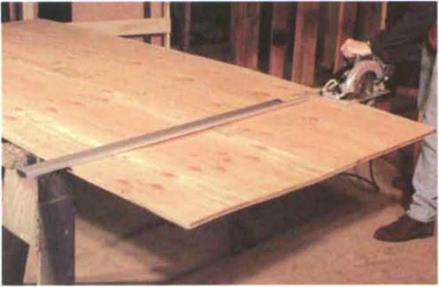

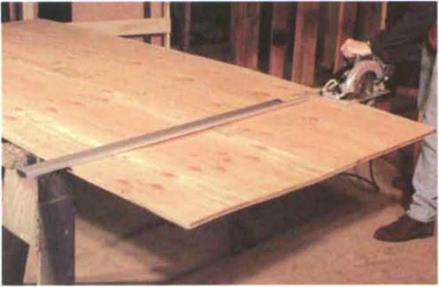

A straightedge ensures a straight crosscut.

|

To make a long, straight crosscut, say on finish – grade plywood or across a door, clamp a good straightedge to the workpiece and slide the saw base along it as you cut (see the photo above). You can make your own straightedge, but I use a commercial one from Griset Industries (see Sources on p. 198) that is arrow-straight and easy to clamp to the workpiece.

Another way to make a straight crosscut is to use a shootboard, which is simply a straightedge with a fence (saw guide) screwed to it. You can buy a shootboard (Olive Knot Products makes an adjustable one—see Sources on p. 198), but it’s pretty easy to make one.

Just cut two pieces of 1/2-in. plywood—one 8 in. wide and one 1V2 in. wide—as long as the material you wish to cut. Glue or screw the 11/г-іп. piece to one edge of the 8-in. piece. The wider piece will be the base, and the thinner piece will serve as the fence. Place the circular saw on the base against the fence and cut off any excess material.

To use a shootboard, clamp it to the workpiece with the front edge of the base right on the cut line.

Place the saw on the shootboard against the fence, reset the blade so that it extends 1/e in. below the stock, and cut. The base will also keep the wood fibers from tearing out at the end grain (for more on preventing tearout, see the sidebar on p. 47).

RIPPING

A cut along the length of a board is called a rip cut, and it can be done in several ways. Most ripping is done simply by cutting freehand along a pencil mark or chalkline that has been laid out on a board. Again, make sure the stock is adequately supported and that the saw isn’t forced or twisted during the cut.

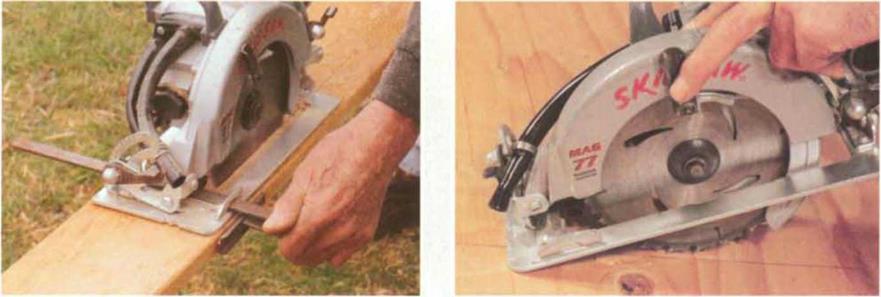

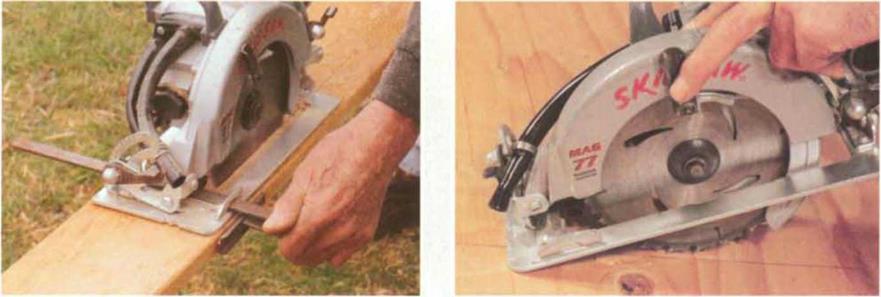

When you need an accurate rip cut, use a ripping – guide attachment. A good one is available from Prazi-USA (see Sources on p. 198). Another type of guide fits into the slots on the front of the saw base. Both guides work like a table-saw fence and can be adjusted to various widths (see the photo below). Both have a flange on one end that you hold against the edge of a board as you make the cut. If you have a flat saw base, you can attach a stair gauge to the front edge and use it as a ripping guide (see the photo at right).

PLUNGE CUTTING

A plunge cut is made in the middle of a board and is used, for instance, to cut a window opening in the center of a piece of plywood sheathing.

To make a plunge cut, lean the saw forward over the cut line so that it is resting on the front edge of the saw base with the blade about 1 in. from the wood (see the bottom right photo). Use the lever to raise

the guard and expose the blade, then start the saw and, using the front edge as the hinge point, slowly lower the blade into the wood. Hold the saw with both hands and continue the cut, following the cut line. When you get to the end of the cut, turn the saw off and let the blade stop spinning before pulling it out.

If you need to finish a cut near where you started, don’t try to back the saw into the cut. Instead, turn the saw around and finish from the opposite direction.

|

A stair gauge attached to a saw base makes a simple but effective ripping guide.

|

|

A ripping-guide attachment makes it easy to cut on a straight line, even on long stock. (Photo by Roe A. Osborn.)

|

|

|

To start a plunge cut, lean the front edge of the saw base over the cut line, and start the saw with the blade about 1 in. from the wood.

|

|

|

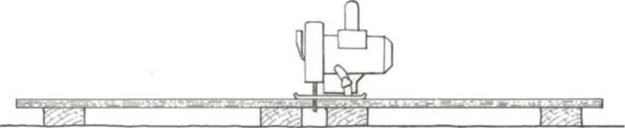

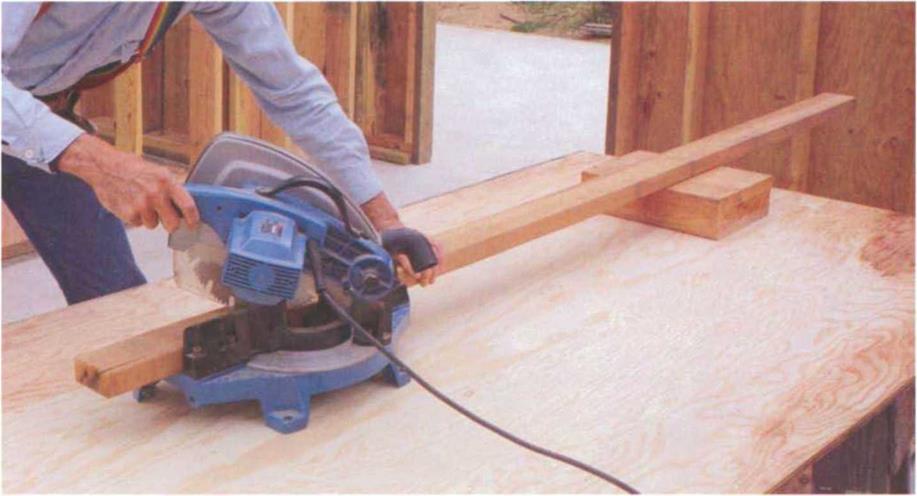

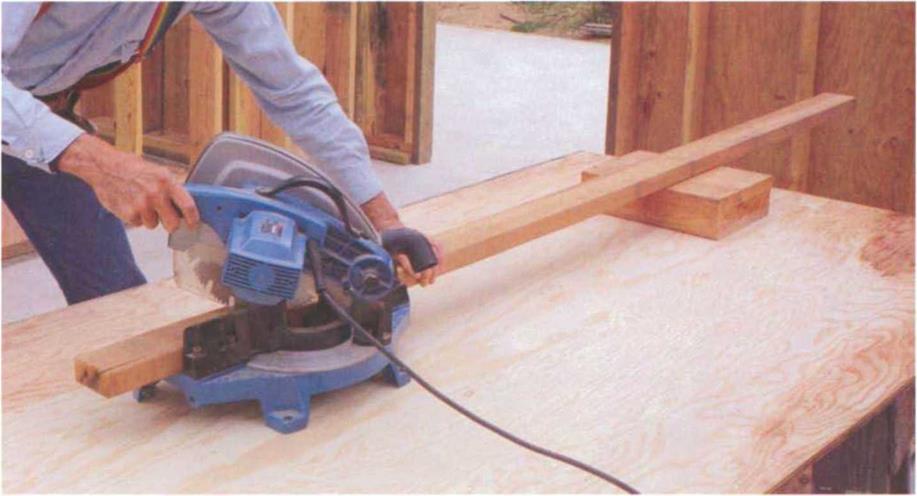

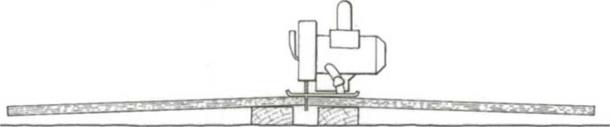

When cutting long stock with a miter saw (also called a chopsaw), support one end on an extension table, on a sawhorse, or on blocking, as shown here.

|

|

which can crosscut a 2×6, because of its versatility. Smaller models work well for cutting trim, while larger ones can cut through 4x stock.

There are now a variety of power miter saws that offer even greater capacity and versatility than the simple version just described. Some of the newest sliding compound miter saws have the capacity to crosscut up to a 4×12. They also tilt from side to side to allow you to make a compound (double-angle) miter cut. These saws are rugged enough for daily use by framers, yet are plenty accurate for finish work.

Some power miter saws come equipped with extension wings for the table, which can be useful for cutting relatively short stock. For longer stock, you may need extra support so that the stock

doesn’t lift and pinch the blade. Extension tables for miter saws are available, but I usually support long stock with a block set to the side of a job – made table (see the photo above).

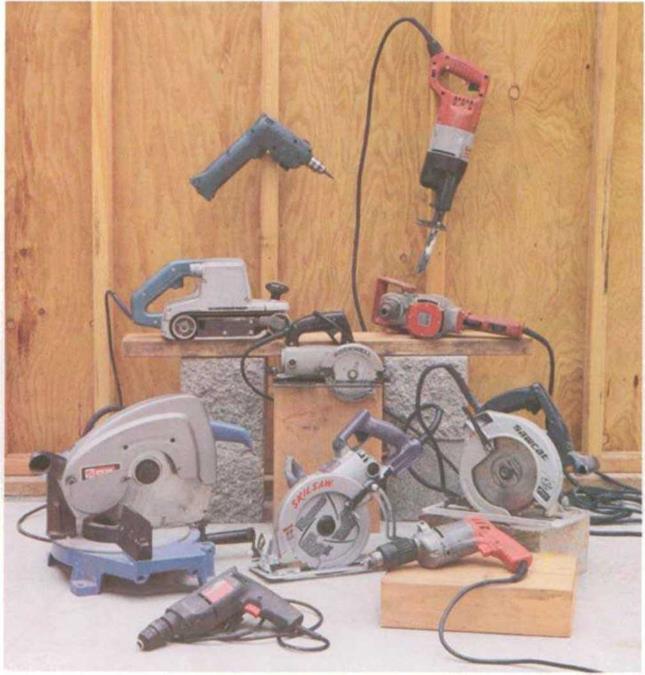

Reciprocating saw

Years ago, every carpenter had a keyhole saw for cutting in tight places. Nowadays carpenters use a reciprocating saw, which is basically a keyhole saw with a motor. It’s the tool of choice for remodeling work, such as tearing out walls, replacing doors and windows, or removing old cabinets, because it cuts through wood, metal (including nails and pipes), plaster, and plastic. It can also get into places you can’t reach with a circular saw: for instance, when you need to cut a hole in a subfloor right against a wall.

Preventing tearout

Tearout of wood fibers is a common occurrence when cutting wood, especially during crosscutting. This is okay for framing but not for finish work.

One way to prevent tearout is to lay a straightedge directly on the cut line and run a utility knife or a pocketknife along the line to score the wood fibers on the cutoff side of the line. This will prevent them from lifting up as the saw makes the cut.

Another way to prevent tearout is to lay a strip of masking tape over the area to be cut. The tape will hold the wood fibers in place during the cut. To prevent the tape from lifting any loose fibers from the wood when removing it, pull it toward the edge of the board.

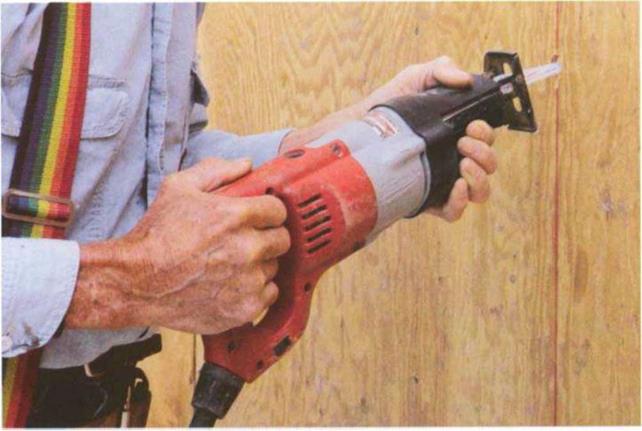

The first reciprocating saws had only one speed, but most of them now have either a two-speed or a variable-speed switch. While wood can be cut at high speed, hard materials—such as metal pipe—need a lower speed to minimize the heat generated by friction. The variable-speed mechanism also makes it easier to do plunge cuts and precision work. When using a reciprocating saw (say, for cutting into an existing wall), be careful not to cut through plumbing or wires. It’s a good idea to shut off power to any nearby electrical circuits when making blind cuts, but it’s an even better idea to avoid making blind cuts whenever you can. Use both hands when using this saw, and hold the shoe

against the material being cut to make the cut faster and safer (see the top photo on p. 49).

Reciprocating saw blades are available in lengths from Vh in. to 12 in. A good all-purpose size is 6 in., which is large enough for most jobs and easier to control than longer blades. In general, use the shortest blade that will do the job. I prefer to use bimetal blades, which are more expensive than standard blades but can cut both wood and metal. If you bend a blade while cutting, don’t worry. Blades can usually be straightened and reused, and you usually don’t even have to take them out of the saw to do it.

Power-saw safety

• Stay alert at all times. Accidents happen not so much when we are still learning but when we think we have mastered a tool. As a beginner, your mind is focused and you are careful. But once you gain experience, you may feel so confident that you pay less attention to what you are doing.

• Keep small children away from power saws (and other tools).

• Use sharp blades. Dull blades don’t cut well and can cause accidents.

• When changing blades, unplug the saw.

• If the saw has a blade guard, make sure it’s working properly, and use it. Cut scrap wood to practice working with the guard in place so you can get used to it.

• Don’t force a saw. Let it work at its own pace. Forcing a saw can overload the motor, causing it to overheat.

• When you feel the blade bind in the kerf, stop and start over.

• Wear safety glasses or goggles.

• Wear a mask if you are sensitive to sawdust.

• Use hearing protection.

• Don’t use a power saw—or any power tool—when you are fatigued.

• Remove anything that might distract you, such as a loud radio.

• Keep your fingers away from the blade! Blow— don’t brush—sawdust away from the cut line to clear the line as you cut.

However, the blade can get quite hot when cutting, so be sure to use pliers, not your fingers, to straighten it.

figsaw

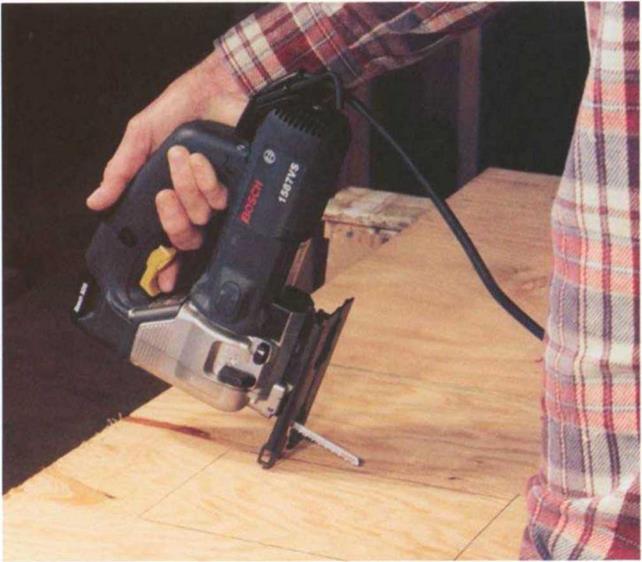

The first carpenter I learned from was a master with a coping saw, which he used to cut intricate patterns. I think he would have loved a power jigsaw (also called a sabersaw), which can literally cut circles around a coping saw. It’s a versatile tool used for cutting circles, curves, and irregular patterns, as well as for making sink cutouts in countertops.

Most jigsaws have an adjustable base plate that allows you to make angled cuts. And I recommend getting a jigsaw with a variable-speed control, which gives more control over the cut through various types of materials. Like its cousin the reciprocating saw, a jigsaw can cut through wood, ceramic tile, plastic, fiberglass, and metal—when equipped with the proper blade.

Jigsaw blades are designed to cut either on the upstroke or on the downstroke, depending on the blade. To avoid tearout on the finish side of a work – piece, keep the finish side down if your

When using a reciprocating saw, place one hand on the handle to control the switch and the other on the rubber boot at the front end of the tool.

To start a plunge cut with a jigsaw, rest the front edge of the base plate on the workpiece with the blade clear of the wood. Start the saw and ease the blade into the wood.

blade cuts on the upstroke. Keep the finish side up if your blade cuts on the down stroke. To reduce vibration and chipping, hold the base plate firmly against the surface of the material when making your cut, letting the saw work at its own pace. If you push it too hard, especially through a knot, the blade could break. On a tight curve, cut very slowly so as not to bind or break the blade. And don’t brush sawdust away from the cut line with your hand; instead, blow the dust away and save your fingers.

Both jigsaws and reciprocating saws can cut an opening in thinner material, such as plywood paneling, without drilling an initial pilot hole. To make a plunge cut with a jigsaw, tilt the saw forward and rest the front edge of the base plate on the workpiece with the blade clear of the wood (see the bottom photo on

p. 49). Then start the saw and ease the blade slowly into the wood. Once the blade penetrates all the way through, the saw can be placed in its normal vertical position and the cut completed.

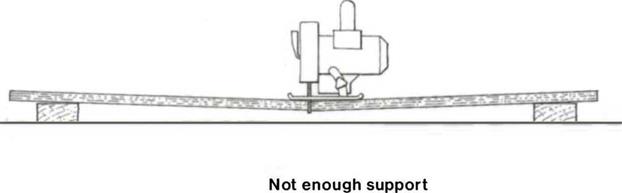

The stock sags on the end, pinching the blade.

The stock sags on the end, pinching the blade.