Teaching By Example

Embracing less in a culture founded on the precept of more is counter-cultural, but it need not be self-consciously so. To do what we know to be right takes effort enough. There is no need to waste our much-needed energy on actively trying to change this spendthrift society. The tangible happiness of a life well lived is worth a thousand vehement protests.

Magazines, television and billboards incessantly insist that the cure for what ails us will be revealed by earning and spending more and increasing square footage. But the security and connectedness we seek are unobtainable so long as we continue to surround ourselves with these symbols of security and connectedness. Our desire for that which pretends to be success and our fear of not having it bar us from feeling genuinely fulfilled. Happiness lies in understanding what is truly necessary to our happiness and getting the rest out of the way.

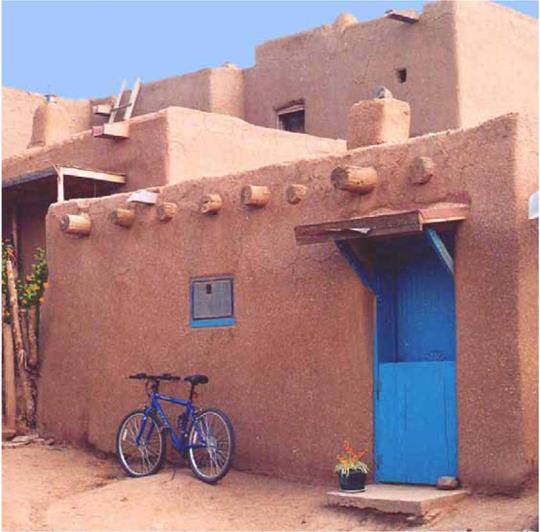

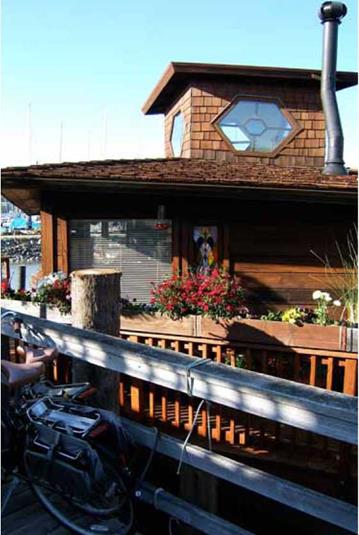

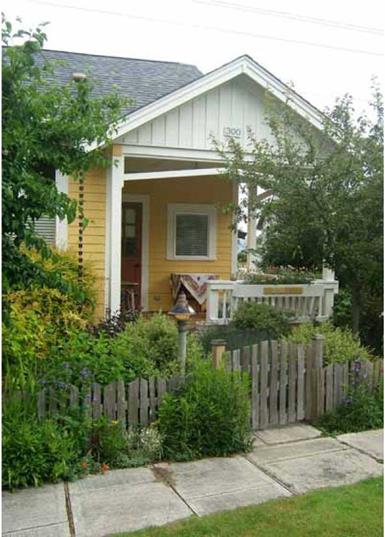

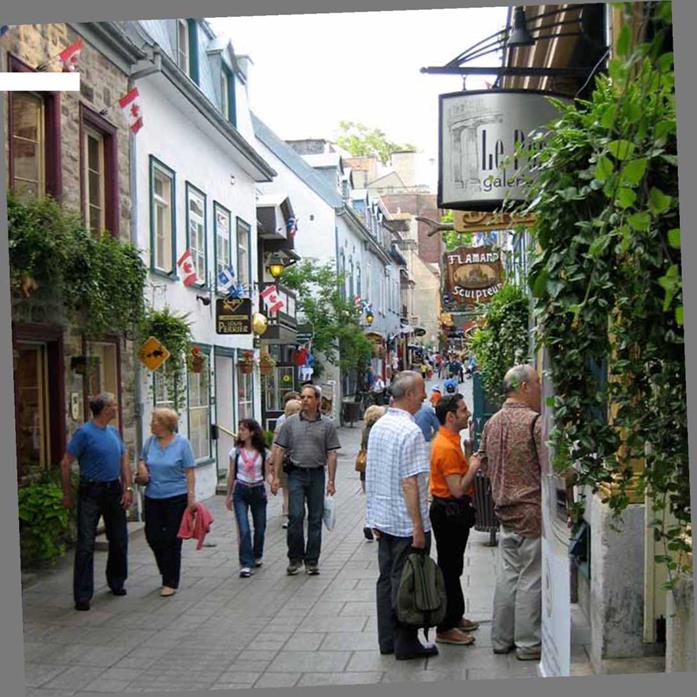

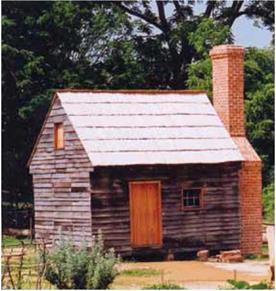

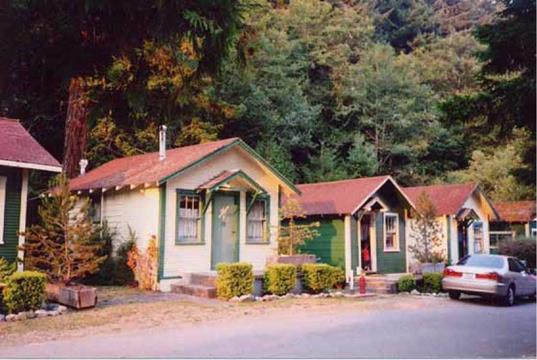

Simplicity is the means to understanding our world and ourselves more clearly. We are reminded of this every time we pass by a modest little home. Occasionally, between the billboards, a tiny structure reveals a life that is unfettered by all of the excesses. Such uncomplicated dwellings serve to remind us of what we can be when our striving and fear are abandoned. Each person who chooses to live so simply inadvertently teaches the virtue of simplicity.

In a society as deeply mired in over-consumption as our own, embracing simplicity is more than merely countercultural; it can, at times, be downright scary. We are in many ways a herd animal, and to take the path less traveled requires courage. We are living in a system that, if left to its own devices, would have us in debt up to our eyeballs and still clamoring to purchase more things than we could use in a thousand lifetimes. Simplification requires that we consciously resist this system and replace it with a more viable one of our own making. For some of us, it requires that we either break laws or expend the time and money required to change those laws that currently prohibit an uncomplicated life.

In any case, anyone who sets out to create such a life should know that he or she is not alone. Though our current system discourages (even prohibits) such freedom, we are all, on some deeper level, familiar with our own need for simplicity. Order is a human concept that expresses an inherent human need. On at least the most intuitive level, we all see the beauty in a well-made, small dwelling because the necessity such a structure expresses resonates with the necessity within each of us. The fear that these little places sometimes inspire is not really so much one of lower property values; it is the fear that these simple dwellings may inadvertently tell us something important about ourselves that we are not ready to face.

|

Trinity Park, MA |

|

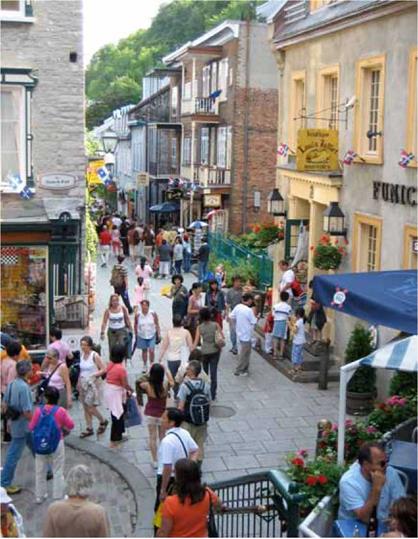

Trinity Park, MA (top) & a San Francisco Bungalow Court (above) |

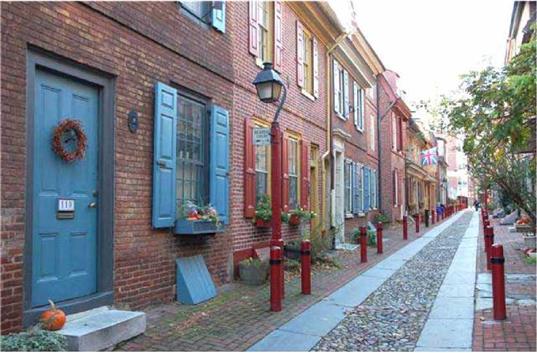

We are in the midst of a housing crisis. The Bureau of the Census has determined that more than forty percent of this country’s families cannot afford to buy a house in the U. S. Over 1,500 square miles of rural land are lost to compulsory new housing each year. An immense portion of this will be used for nothing more than misguided exhibitionism. We clearly need to change our codes and financing structure and, most importantly, our current attitudes about house size.

We are in the midst of a housing crisis. The Bureau of the Census has determined that more than forty percent of this country’s families cannot afford to buy a house in the U. S. Over 1,500 square miles of rural land are lost to compulsory new housing each year. An immense portion of this will be used for nothing more than misguided exhibitionism. We clearly need to change our codes and financing structure and, most importantly, our current attitudes about house size.

It is illegal to inhabit a tiny home in most populated areas of the U. S. The housing industry and the banks sustaining it spent much of the 1970s and 1980s pushing for larger houses to produce more profit per structure, and housing authorities all cross the country adopted this bias in the form of minimum-size standards. The stated purpose of these codes is to preserve the high quality of living enjoyed in our urban and suburban areas by defining how small a house can be. They govern the size of every habitable room and details therein. By aiming to eliminate all but the most extravagant housing, size standards have effectively eliminated housing for everyone but the most affluent Americans.

It is illegal to inhabit a tiny home in most populated areas of the U. S. The housing industry and the banks sustaining it spent much of the 1970s and 1980s pushing for larger houses to produce more profit per structure, and housing authorities all cross the country adopted this bias in the form of minimum-size standards. The stated purpose of these codes is to preserve the high quality of living enjoyed in our urban and suburban areas by defining how small a house can be. They govern the size of every habitable room and details therein. By aiming to eliminate all but the most extravagant housing, size standards have effectively eliminated housing for everyone but the most affluent Americans.