Streets Too Wide

One of the most readily-apparent products of zoning is the wide, suburban street. Roadways built before zoning emerged typically have 9-foot wide travel lanes. Now, most are required to have lanes no less than 12 feet wide. This allows for what traffic engineers call "unimpeded flow,” a term some critics have aptly interpreted as "speeding”.

Safety concerns have played a no less significant role in the widening of America’s streets. During the Cold War, AASHTO (the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials), pushed hard for streets that would be big enough to facilitate evacuation and cleanup during and after a nuclear crisis. Fire departments, too, continue to demand broader streets to accommodate their increasingly large trucks. Streets today are often fifty feet across because standard code after the 1940s has required them to allow for two fire trucks passing in opposite directions at 50 miles per hour.

Sometimes it is not a street’s width but its foliage that presents the problem. Departments of transportation routinely protest that trees [also referred to as FHOs (Fixed and Hazardous Objects)] should not line state roads. Now, certainly safety is important, but the high costs of wide, treeless roads (financial and otherwise) might warrant some kind of cost/benefit analysis. Fortunately, we have several. The most widely published is that of Peter Swift, whose eight-year study in Longmont, Colorado, compared traffic and fire injuries in areas served by narrow and wide streets. He found that, during this period, there were no deaths or injuries caused by fire, while there were 227 injuries and ten deaths resulting from car accidents. A significant number of these were related to street width. The study goes on to show that thirty-six footwide streets are about four times as dangerous as those that are twenty-four

|

|

feet across. According to Swift’s abstract, "current street design standards are directly contributing to automobile accidents.”

This study and others like it suggest that we should begin to consider the issue of public safety in a broader context. Fire hazards are only part of a much larger picture. The biggest threat to human life is not fire but the countless accidents caused by America’s enormous roadways.

Suburbs did not grow out of any particular human need or evolve by trial and error as an improvement to preexisting types of urbanism. The ‘burbs, as we know them, were invented shortly after World War Two as a means of dispersing urban population densities. This invention precluded virtually all lessons learned from the urban design of years past. Even the most universal principles of good planning, used successfully from 5000 B. C. Mesopotamia to 2005 A. D. Seaside, Florida, were ignored. Perhaps the most startling departure from tradition was the omission of contained outdoor space. Human beings have a predilection towards enclosure. We like places with discernible boundaries. To achieve this desired sense of enclosure, a street cannot be too wide. More specifically, its breadth should not far exceed the height of the buildings that flank it. A street that is more than twice as wide as its buildings are tall is unlikely to satisfy our inherent desire for orientation and shelter. Rows of trees can sometimes help to delineate a space and therebyincrease the recommended street-to-building ratio, but generally, anything wider than a proportion of 2:1 will compromise the quality of an urban environment.

America’s suburbs incessantly ignore the 2:1 rule. The distance from a house to the one directly across the street is rarely less than five times the height of either structure, and there are seldom enough well-placed trees around

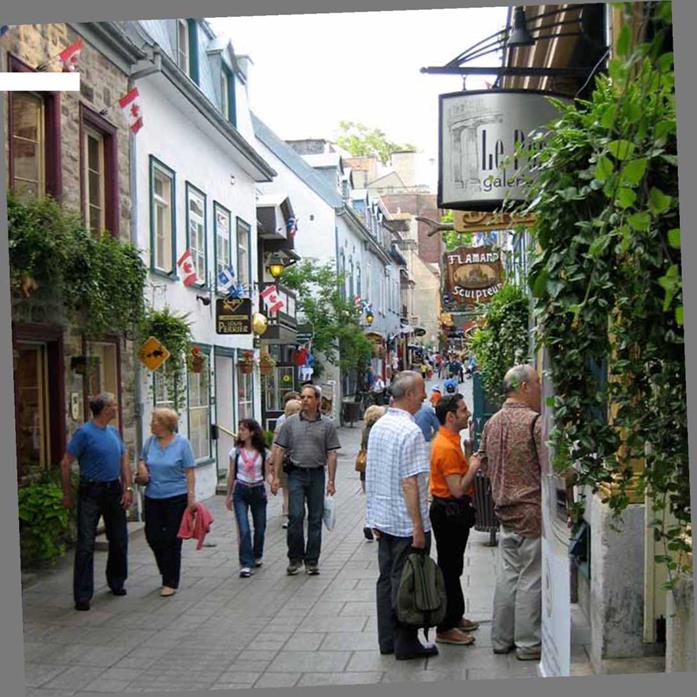

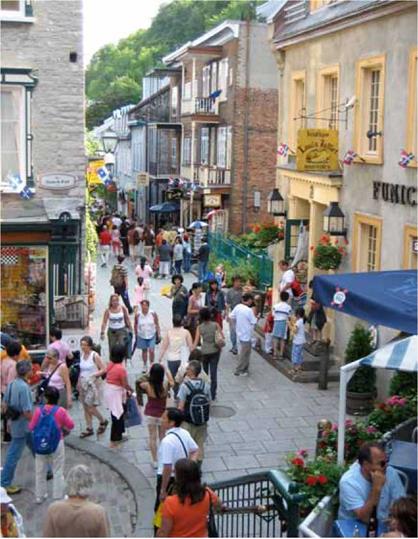

![]() Sprawl, U. S.A. (pages 48 & 49). Quebec City (opposite)

Sprawl, U. S.A. (pages 48 & 49). Quebec City (opposite)

to compensate. The empty landscape that results is one most of us have become far too familiar with.

To evoke a sense of place, a street, much like a dwelling, must be free of useless space. When given a choice, pedestrians will almost always choose to follow a narrow street instead of a wide one. That we frequently drive hours from our suburban homes to enjoy a tiny, lakeside cabin or the narrow streets of some old town is nearly as senseless as it is telling. That we then return to toil in our cavernous dwellings on deficient landscapes is more senseless, yet. The environments we see pictured in travel guides are typically the walkable, little streets of our older cities. The marketing agents who produce these guides are undoubtedly no less aware of our desire for contained, outdoor space than were the architects of the streets depicted.

People like places that were designed with people in mind, so it should come as no surprise that property values and street widths appear to share an inverse relationship. Apparently, we are willing to pay more for less pavement. The funny thing is that the skinny streets we like are actually much cheaper to build and maintain than the wide ones we so often choose to live with.

|

Quebec City |

Leave a reply