Water resources for Persia and the silk road

The traveler coming from Taklamakan or India enroute for the Roman or Arab worlds, whether he crosses the Kush or the high passes of Pamir that lead to Bactria, encounters the vast arid zone of the Persian plateau (or Khorassan). The plateau’s sparse and unreliable water resources were exploited by means of several irrigated oases during the

Bronze Age. Then much larger irrigated zones were developed beginning with the period of the Achaeminde Persians. This development was based on the mining of groundwater through qanats. The earliest evidence of these projects is the account of the historian Polybius, who describes an expedition led by the Seleucid king Antiochus III against the Parthians in 210 BC. When the army of Antiochus penetrates into the desert, forcing his enemy to retreat, the Parthian sovereign Arsace II has his horsemen destroy the qanats of the region:

“Arsaces had expected Antiochus to advance as far as this region, but he did not think he would venture with such a large force to cross the adjacent desert, chiefly owing to the scarcity of water. For in the region I speak of there is no water visible on the surface, but even in the desert there are a number of underground channels communicating with wells unknown to those not acquainted with the country. About these a true story is told by the inhabitants. They say that at the time when the Persians were the rulers of Asia they gave to those who conveyed a supply of water to places previously unirrigated the right of cultivating the land for five generations, and consequently as the Taurus has many large streams descending from it, people incurred great expense and trouble in making underground channels reaching a long distance, so that at the present day those who make use of the water do not know whence the channels derive their supply. Arsaces, however, when he saw that Antiochus was attempting to march across the desert, endeavored instantly to fill up and destroy the wells. The king when this news reached him sent off Nicomedes with a thousand horse, who, finding that Arsaces had retired with his army, but that some of his cavalry were engaged in destroying the mouths of

o

the channels, attacked and routed these, forcing them to fly, and then returned to Antiochus.”0

As is noted by Henri Goblot in his study of the qanats, the above text shows that the wells were not very well maintained under the Parthian regime, since nobody knows the layout and source of the underground channels. The Parthians began as nomads, caring little for the infrastructure of irrigation. It is certain that the system of qanats was once again developed under the Sassanides, and especially under the Arabs and the Turks between the 9th and 11th centuries. The city of Nishapur, in Khorassan, owes its prosperity to these wells from the beginning of the 9th century. A text from 830 AD describes how the judges of all Khorassan and even of Iraq came together to write a book of law regarding use of the qanats (the Kitab al Kani), given the absence of any prior legal precedents or earlier Muslim law. The Persian mathematician al-Karagi, living in Baghdad, wrote another more technical account of the qanats in about 1010 AD.[306] [307]

At Marw (Merv, Antiochia of the Margiana to the Greeks), the river Murgab has a dam whose age is difficult to determine, though we know that it is maintained during the Islamic period. This dam serves to stabilize the upstream progression of settled areas which we have discussed at the end of Chapter 2.[308] It also leads to the regrouping of dwellings inside an enclosure, and provides for a more reliable and regular functioning of the system of irrigation – even though the area also is equipped with qanats. Some

10,0 men are employed, under the direction of a superintendent, to maintain the hydraulic system in the 10th century.

At the beginning of the 13 th century the Mongols destroy not only the cities, but also the hydraulic systems. Marw and Balkh (Bactra, ancient capital of Bactria) are abandoned, but Nishapur and Harat rise from their ashes, as does Samarcand, the great center of the silk trade in Sogdiana. The qanats are rebuilt; Marco Polo notices them to the north of Kerman in about 1272:

“The fourth day (of crossing the desert), we came upon a fresh-water river that flows mostly underground, but in certain places, there are openings created by the waters, where one can see it flow, but then it immediately returns below the ground. Nonetheless, one can drink to ones full. Not far from there, travelers who are spent by the ardors of the desert they had crossed, rest and refresh themselves and their beasts.”11

When the traveler Ibn Battuta visits Nishapur about 1335, he writes that this city is called “little Damascus” for the abundance of its running water and the lushness of its gardens. A Persian historian of the 15th century reports the words of another Arab voyager who was not entirely happy with his experience:

“What a beautiful city Nishapur would be if its canals were above ground and its inhabitants 1 2

underground!”

The qanats are still in operation in this area, but it is not possible to assign dates to them individually. In Iran there are twelve groups of qanats, some along an axis parallel to the Caspian Sea, then oriented toward the east, i. e. from Tehran to Nishapur; and others on the eastern foothills of the Zagros mountains (Ispahen) and in the center of the region of Zarand-Kerman (see Figure 7.1). Among the two thousand qanats that have been studied the longest is 50 km, in the center of the area where the land is relatively flat. But 81% of the qanats are shorter than 5 km, and 36% of them are between 500 m and 2 km. The delivered discharged is normally between 10 and 100 m3/hour. Among the 180 qanats in the Tehran region, the depth of the mother well at the head is usually between 10 and 50 m, but it can be more than 100 m or even 150 m in certain cases.[309] [310] [311]

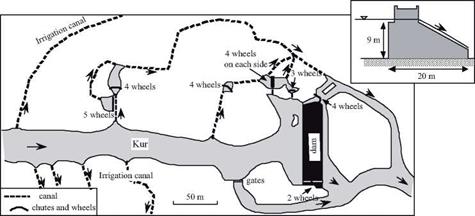

Important rivers such as the Karun and the Kur rise in the Zagros and Fars mountains of southern Persia. Rather typical hydraulic works are constructed along the Karun, constituting masonry overflow weirs combined with bridges, beginning in the Sassanide period. Foremost among these is the 520-m long weir built by Roman prisoners around 260 AD after the capture of the Emperor Valerius. These projects typically raise the river level to supply irrigation canals. But in addition, beginning in the Arab period, they supply water to batteries of mills, or norias. The Amir and Feizabad dams on the river Kur, near Shiraz in Fars, are 9 and 7 meters high and 103 and 222 meters long, respectively. These dams are equipped with an impressive number of water mills: no less than 30 for the Amir (Figure 7.4) and 22 for the Feizabad. These mills have horizontal wheels on vertical axes, and are driven by water falling vertically onto their blades:[312]

“Adud al-Dawla closed off the river, between Shiraz and Istakhr, with a great wall, reinforced with lead. The water that accumulated behind this dam formed a great lake. Above this lake, on its two sides, there are hydraulic wheels like those that we have mentioned in Khuzistan. Below each wheel, there is a mill, and today this is one of the marvels of Fars. Later, he constructed a city. Water flows through canals and irrigates 300 villages in the valley.”[313]

|

Figure 7.4 The Amir installation on the Kor river, in Fars (10th century) and its thirty water wheels (after Schnitter, 1994). |

The regions of Bukhara and Samarcand are to the northeast of Khorassan, between the Oxus and Iaxartes rivers. If Khorassan is the land of qanats, Bactria and Sodgiana are the lands of gravity irrigation, through river water diverted into canals by small hydraulic structures. This practice in the Oxus basin stems from the Bronze Age (Figure 2.30), and becomes fully developed in the Greek kingdom of Bactria, then under the Kuchans, between the 3rd century BC and the 2nd century AD. Samarcand solidifies its identity as a great commercial crossroads in the silk trade from this time on. Around Samarcand and Bukhara irrigation networks originating from the Zeravchan River branch out over tens of kilometers.

Ancient Samarcand is located on high ground, and benefits from an advanced water – supply system – a conduit forming a siphon that is destroyed during the siege of the city by the Mongols of Ghengis Khan, in 1219. The city is rebuilt right on the river banks, making it possible to use norias to provide water for the city and its gardens. Ibn Battuta visits Samarcand around 1335, a little more than a century after its pillage. Even though the ruins remain visible, it has clearly become a beautiful city once again:

“… I reached Samarcand, one of the geatest cities, the most beautiful and the most superb. It is located on the wadi al-Qassarin (River of the Fullers) on which there are hydraulic wheels for irrigation of the gardens. The inhabitants get together, after prayers, to stroll and amuse themselves along the banks of the river where one can see benches and seats for resting, and stands that sell fruits and other consumables. Formerly there were, along the banks, imposing palaces and edifices that lead one to imagine the ambition of the inhabitants of Samarcand. But most of these were destroyed, as was a large part of the city [….]. In the city, one can see gardens.”[314]

Samarcand is known for the quality of its paper. Fullers (water hammers that shred and mash linen cloth to produce fiber for paper protection) powered by hydraulic force lend their name to the small river that feeds them, River of the Fullers, a tributary of the Zeravchan. Strong Turk-Mongol regimes launch their raids on surrounding lands from central Asia, where they also develop some new water resources. In the 11th century, the Ghaznavid Turks build two dams in the Samarcand region, 8 and 15 meters high, and 25 and 52 meters long. They also build another larger structure 23 km to the north of their capital city Ghazni, in the region of present-day Kabul; it is 32 meters high and 220 meters long. The Seljuk Turks who succeed them rebuild a dam at Marw on the Murgab River to provide water for the oasis, a dam that will be rebuilt yet again by the Timurids so the oasis can be repopulated.[315] [316] In the 14th century, Tamerlan and his successors establish Samarcand as the capital of a great central Asian kingdom, and build still more dams in the regions of Teheran, Kashan, Tabas and especially near the new city of Mashadd (not far from Nishapur), present-day capital of Khorasan. Near Kebar and Tabas are three arch dams, among the first known to exist after the few Roman and Byzantine arch structures. The largest, 50 km to the

southeast of Tabas, is 28 meters long and 60 meters high, a record that is destined to

18

stand for quite a long time.

Leave a reply