Water lifts, paddlewheels, and water mills in the world of Vitruvius

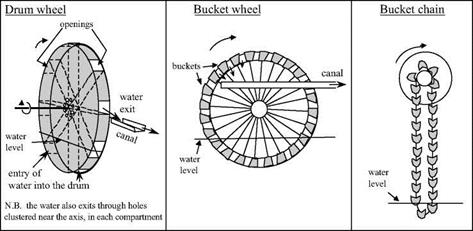

Vitruvius provides the oldest known description of a water lift powered by hydraulic force, or noria, and of a water mill. This description comes immediately after that of manual water lifts (drum wheel, bucket wheel: see Figure 6.20):

“Wheels on rivers are constructed upon the same principles as those just described (manual lift wheels). Round their circumference are fixed paddles (pinnae), which, when acted upon by the force of the current, drive the wheel round, receive the water in the buckets, and carry it to the top with the aid of treading; thus by the mere impulse of the stream supplying what is required.

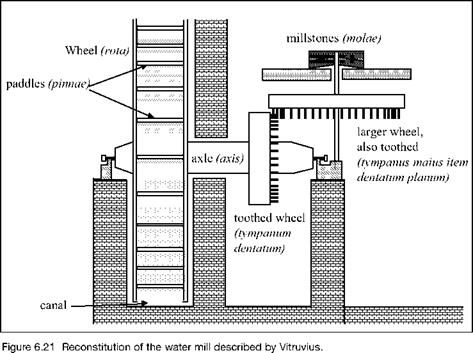

“Water mills (hydraletae) are turned on the same principle, and are in all respects similar, except that at one end of the axis they are provided with a drum-wheel, toothed and framed fast to the said axis; this being placed vertically on the edge turns round with the wheel. Corresponding with the drum-wheel a larger horizontal toothed wheel is placed, working on an axis whose upper head is in the form of a dovetail, and is inserted into the mill-stone. Thus the teeth of the drum-wheel which is made fast to the axis acting on the teeth of the horizontal wheel, produce the revolution of the mill-stones, and in the engine a suspended hopper supplying them with grain, in the same revolution the flour is produced.”[250]

Figure 6.21 is an attempt to reconstitute the devices described by Vitruvius. We

|

Figure 6.20 The manual water lifts described by Vitruvius, the possible origins of the noria and water mill. The lift height increases from left to right. |

recall that he was a contemporary of Augustus (about 25 BC), and therefore came after the reign of Mithridate, though by only a few decades. He doesn’t enlighten us on the details of the innovation much better than did the Greek sources that we cited in Chapter 5. These details and their origins therefore remain somewhat obscure. However, two clues enable us to form at least a rough idea of how the devices operated.

|

|

The first clue is Vitruvius’ outline, the order in which he describes the different machines. He puts his description of the water mill in between those of the water lifts – as in Figure 6.20. He first describes the drumwheel, then the bucket wheel, and finally the bucket chain. All three machines are powered by human muscular force, and raise water to increasing heights in the order they are listed. It is after these descriptions that Vitruvius describes the paddle wheel powered by the force of the current and equipped with buckets to lift the water, and then finally the mill that turns a grinding stone using hydraulic force.

Vitruvius’ work then comes back to lifting machines, presenting two inventions of the 3rd century BC that we have already seen: the Archimedes screw or limagon, and the pump of Ctesibios.[251] Certain authors[252] believe it is possible that the order in which these machines are described, an order whose logic is not at all obvious, must correspond to a technical genealogy of these wheels. The manual bucket wheel could have been perfected through the addition of paddles, so that it could be powered by the force of the current. In this case the paddle wheel could have been used to lift water (this is the noria, an invention destined to have a glorious future in the Orient), before it was realized that the rotation of the wheel could, through appropriate gearing, be used to turn a millstone. Other authors[253] propose that the vertical-axis mill (having a horizontal millstone) was invented first, since it does not require reduction gearing to turn the stone. Moreover, this mill appears in China at about the same time, as we see further on in Chapter 8.

A second clue as to the first use of the paddle wheel can be found a bit further on in the same book X of Vitruvius. There, he describes procedures “passed down to us from our ancestors” (which ones?) to measure travel distances over land or water; these would be “hodometers”. After describing the adaptation of the idea to chariots, Vitruvius then describes an analogous procedure for measuring the distance traversed through the water by boats. It is the paddle wheel that comprises the essential part of this instrument:

“In navigation, with very little change in the machinery (i. e. the hodometer for wheeled chariots), the same thing may be done. An axis is fixed across the vessel, whose ends project beyond the sides, to which are attached wheels four feet in diameter, with paddles (pinnas) to them touching the water. [….]

“Thus, when the vessel is on its way, whether impelled by oars or by the wind, the paddles of the wheels, driving back the water which comes against them with violence, cause the wheels to revolve, whereby the axle is also turned round, and consequently with it the drum-wheel, whose tooth, in every revolution, acts on the tooth in the second wheel, and produces moderate revolutions thereof.”[254]

We know that on modern ships a common instrument for measuring the speed is a small paddle wheel. However the procedure described by Vitruvius appears curious to say the least, and it seems doubtful that its use was widespread.

Leave a reply