The Yellow River, a terrible friend

The first historical treatise from China dates from around 100 BC. This is the work of Sima Qian,[382] who had an official position in the court of the Emperor Wudi of the Hans at the beginning of the imperial era. Sima Qian revived and perpetuated the legendary attribution of the ancient course of the Yellow River to Yu the Great, undoubtedly with some measure of exaggeration. He gives us a rather precise description of the ancient course (Figures 8.2 and 8.3):

“The documents of the Xia Dynasty tell us that Emperor Yu spent thirteen years controlling and bringing an end to the floods and during that period, though he passed by the very gate of his own house, he did not take the time to enter.

Of all the rivers, the Yellow River caused the greatest damage to China by overflowing its banks and inundating the land, and therefore he turned all his attention to controlling it. Thus he led the Yellow River in a course from Jishi past Longmen and south to the northern side of mount Hua; from there eastward along the foot of Dizhu mountain past the Meng ford and the confluence of the Lo River to Dapei. At this point Emperor Yu decided that since the river was descending from high ground and the flow of the water was rapid and fierce, it would be difficult to guide it over level ground without danger of frequent disastrous breakthroughs. He therefore divided the flow into two channels, leading it along the higher ground to the north, past the Jiang River and so to Dalu. There he spread it out to form the Nine Rivers, brought it together again to make the backward flowing river (this is the lower portion of the river which has tidal influence), and thence led it into the gulf of Bohai.”[383]

The reader may note that the great historian recognizes the hydraulic consequences of the change of slope where the river flows out onto the plain, as well as the effects of the tide. These were surely personal observations, for Sima Qian had traveled all across China.

The Yellow River owes its name to the color of the sediments it carries. During floods it is nearly a river of mud, having one of the world’s highest concentrations of sediment. Nearly 5,500 km long, in its middle reaches it flows for 1,200 km across a plateau of loess, carrying fine sediments deposited by the wind. Once the river arrives on the plain, its bed slope suddenly decreases and the water velocity is consequently reduced, as is noted by our historian.[384] [385] As the water velocity decreases, the particles in suspension deposit onto the bed.

Since very early times the Chinese have constructed dikes to protect villages and fertile lands from the floods. The deposited sediments accumulate between these dikes, and

21

this of course raises the bed of the river relative to the plain surrounding it. Quite

rightly, Chinese tradition emphasizes both the importance of dredging the riverbed during low-water periods and the importance of building dikes. As we have seen in Chapter 1, it was in dredging the bed of the river that Yu succeeded in conquering the waters; his father Kouen, who only built dikes, had failed in trying to contain the river.

Failure to dredge the riverbed inexorably ends up causing an overflow and dike rupture. The river flows onto the plain with consequences that one can easily imagine, and it may then wander over large distances and establish a new course completely different from that in which it had formerly been contained by dikes. There have been nearly

2,0 dike ruptures recognized in Chinese history up to the present time, during which the course of the Yellow River has undergone 26 significant changes.[386] Over the course of history, the irrigated and fertile plain has become more and more densely populated – and therefore the consequences of inundation become more and more serious.

|

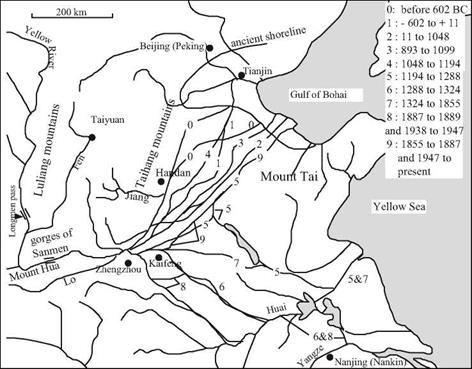

Figure 8.2 The principal historical courses of the Yellow River. N. B. Between 168 and 132 BC, the river flows into the Huai to the south. Moreover, courses 2 and 3 most often comprised two distinct arms each. Finally, it is probable that courses 5 and 7 existed since 1187, and that courses 5 and 6 functioned up until 1495. Other temporary arms are not shown on this map. |

The principal flood events took place between the 2nd century BC and the beginning of the Christian era (Figure 8.9), then again between the 11th and the 14th centuries, when the Yellow River flowed to the south of Shandong and joined the Huai. It is not until the 19th century that the river comes back to the north, in the bed of the Ji river. From the beginning of the Qin and Han Empires, Chinese history records multiple examples of populations that are ruined and displaced by floods, eventually to be resettled by the central authority in colonized regions at the edges of their former domains.[387]

Leave a reply