. The south of Morocco and the Saharan oases

In 1031 the caliphate of Cordova breaks down, fragmenting into small kingdoms. Alphonse VI of Castilla seizes the opportunity to take Madrid in 1083, then Toledo in 1085. The Andalusians call for help from the only powerful Occidental Arab dynasty of the time, the Almoravides of Morocco. Their chief Youssef ben Tachfin puts an end to the advance of Alphonse VI when he passes through Spain, and he brings Morocco and Andalusia under his unified command. His son Ali, raised in an Andalusian culture, succeeds him in 1106. Andalusian scholars and literati follow him to Marrakesh, capital of the Almoravides. This contact probably explains the appearance of the qanat technology in Morocco.

The Almoravides, Berbers from the south, had occupied Sijilmassa, the great cara

van center of Tafilalet, in 1055, and then conquered all of Morocco and founded Marrakesh in 1060. The construction of the first qanat of Marrakesh is documented thanks to al-Idrissi. Ali decided to build it in 1107, and the project was completed by a certain Obeyd Allah ibn Younous (that is, son of Jonas) al-Muhandes (which means the engineer).

“At the time there was only one garden [….]. Obeyd Allah went to the highest point of land overlooking this garden. There, he had a very large rectangular pit dug, from which he had dug a single outlet that gradually descended (.) to the garden for which it supplied water in a continuous fashion. With the naked eye, one cannot detect, on the ground, any slope that would enable the water to flow from the bottom of the pit to the surface of the garden. To understand this, one must understand the clever trick that was used to supply the water. This trick consisted in evaluating the difference in ground level (from the bottom of the pit to the garden). The Emir of the Muslims, who very much appreciated the work of the engineer Obeyd Allah, paid him with silver and clothing. [….] After that, inspired by the example provided by this man of art, the inhabitants of Marrakesh set about capturing water and bringing it to their gardens, to the point that many of them could only increase in size, buildings growing up around them, embellishing the skyline of Marrakesh.” [348]

According to the text, this Obveyd Allah ibn Younous well understood the technique of the qanats when he came to install them in Marrakesh. If one juxtaposes the dates (the event was 80 years after the taking of Madrid, one year after the birth of Ali, who was raised in contact with the Andalusian literati) and the facts (according to al-Idrissi, it was Andalusian engineers that Ali called upon to build the first bridge on the wadi Tensift), it seems reasonable to presume (as did Henri Goblot) that this engineer came from Spain.

Over a thirty year period some fifty qanats are built on the plain of Marrakesh (the Haouz), where they are called khettaras, bringing 5,000 hectares under irrigation. The Almohades took over from the Almoravides after 1160. They built new qanats and constructed an extended network of canals supplied by the rivers to increase this irrigated land area to 15,000 hectares. After some retrenchment in the 16th century, the irrigated area grows to about 20,000 hectares in modern times. There are some 600 identified qanats, 500 of which were still in service in the middle of the 20th century. These qanats are generally quite shallow, for the water table issuing from the Upper Atlas mountains is only about 20 meters below the ground surface. The qanats are limited by the land slope to only from 500 m to several kilometers long, and the wells are closer together than those of Iran. The average discharge of a qanat at Marrakesh is of the order of 40 m3/hour.[349]

Sugar cane is grown on the plain of Sous and in the haouz of Marrakesh. This crop requires considerable water. Sugar processing is also water-hungry, both in its need for hydraulic energy (mills to grind the cane) and for preparation of sugar bread. This water is most often taken from the rivers, but it can also come from the qanats – both those of

Marrakesh as well as others on the plain of Sous, particularly in the region of Aoulouz and the surroundings of Agadir. The sugar industry quickly grows to play a significant role in the economy of Morocco, a role it maintains up until the 17th century. Important hydraulic infrastructure is developed to support this industry, particularly by the Merinides at the end of the 14th century and then by the Saadians in the 16th century, on the plain of Sous and at Chichaoua in the Haouz.

Fez was established toward the end of the 8th century on a site that was at the center of an agricultural plain and naturally well supplied with water, the terminus of the route that crosses the Atlas near Sijilmassa. In the 11th century the Almoravides build canals to irrigate the gardens of Fez, and also build water mills. Al-Idrissi observed in the 12th century that in the district with the best water supply, al-Qarawiyyin, the delivery and drainage networks were particularly well developed:

“Al-Qarawiyyin has an abundance of water that circulates through all the streets and allyways, in conduits that the inhabitants can open when they wish to wash the neighborhoods during the

night and have them perfectly clean in the morning. In each house, be it large or small, there

53

is a pipe for both clear or dirty water.”

Norias appear in Fez in the 14th century, and numerous water-based activities develop in the city. In the 16th century Leon the African enumerates over a hundred public baths and nearly 400 water mills supporting all sorts of industrial uses.[350] [351] [352]

Sijilmassa is, with Marrakesh and Fez, another grand center of activity in medieval Morocco up to the 14th century:

“Sijilmassa is an important capital, located some distance from a watercourse that disappears to the south of the city. [….] This city is rich in dates, fresh and dry grapes, fruits, cereals, pomegranates and diverse other agricultural products; the city pleases foreigners who come from all directions in large number. [….] The canton possesses mines of gold and silver. [….] Sijilmassa is surrounded by the sands of the desert, its inhabitants use water holes.”[353]

This ancient city was founded in the middle of the 8th century. Recently discovered vestiges have been the focus of American-Moroccan research efforts between 1988 and 1996. The city is located in the Tafilalet, one or two kilometers to the west of the present Rissani (which is some 200 km east of Ouarzazate) near the wadis Ziz and Rheris that descend from the High Atlas. Sijilmassa is a node of communication with the Orient (via Ouargla) and especially with Sudan, a source of gold. Ancient texts present an image of grand agricultural prosperity, the remains being seen in present-day palm groves:

“She (Sijilmassa) has a series of castles, houses and buildings along an abundant water course that comes from the east, i. e. from the desert, and whose flow increases in the summer (with the snowmelt of the High Atlas), much like the Nile. Its waters provide for irrigation of crops,

which along with the use of Egyptian peasants leads, as everyone knows, to very good harvests. In certain years, following floods of this river, water is so abundant that the grains harvested in the previous year grow again without any need to replant the fields.”[354]

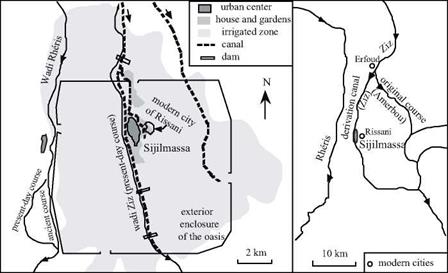

This text suggests a practice of flood-recession agriculture, certainly as in Egypt, but also in conditions that would appear to be close to those that we have described in Chapter 3 for the east of Arabia Felix (Yemen). Similarities in architecture between the ancient cities of Yemen and the ksar (fortified villages) of Tafilalet suggest another possibility -that the hydro-agricultural techniques used at Sijilmassa have their origin in a Yemeni migration. Field studies [355] indeed show that small dams were constructed on the wadi Rheris, to be destroyed several times by floods but then rebuilt in other locations. But it is especially the wadi Ziz that is developed and managed. Initially, the Ziz ran much more to the east, along a course that is today called the wadi Amerbou. At some undetermined time, the course of the Ziz was changed by a dam situated some 15 km to the north of Sijilmassa (opposite the present-day Erfoud, where traces of a stone structure still exist). The wadi was diverted into a canal that runs along the western side of the city of Sijilmassa (Figure 7.17). This canal is in its own right the source of sec-

|

Figure 7.17 The principal hydraulic developments of Sijilmassa (after Messier, 1997). |

ondary derivations for irrigation of the oasis and subsequent return flow to the original course further to the south. This original course (the Amerbou of today) handles the drainage of excess flood waters. Over the centuries this canal becomes the source of the modern watercourse of Ziz.

To complete this broad-brush painting of the water resources of Tafilalet, we should note that along with Marrakesh, this region constitutes the second flowering of qanats of Morocco. Remains of 300 qanats are identifiable today, half of them still in service. Their dates of construction are unknown.

Another very important blossoming of qanats is located in the oases of Gourara, Touat and Tidikelt in present-day Algerian Sahara, south of the western Grand Erg. This is a chain of palm groves clustered around the foot of the Tadema’tt plateau (Figure 7.16).

These oases were undoubtedly populated by migrations of Jewish Berbers from Cyrenaic, the Zenata, fleeing Roman colonialism of the 2nd century AD. But in general we assume that the history of the Saharan qanats reaches back only to the 9th or 10th centuries AD, and that their history is unconnected to that of the old Roman qanats of Libya and Tunisia (Chapter 6), at this time a forgotten technique.[356] The introduction of qanats grew out of new immigration waves from the Orient – we must remember that at this period, the Sahara was not nearly as water-starved as it is today. But without these thousands of qanats the grand oases would not have survived to the present. At the beginning of the 20th century some 400 active ones were known in Gourara (especially on either side of Timimoun); 440 in the Touat chain of oases between Adrar and Tauourirt, where they are the sole source of water; and 125 in the Tidikelt, especially around Aoulef and In Salah. They are from 2 to 15 km long, with very closely spaced wells.[357]

Leave a reply