The qanats: a new technique for obtaining water

When surface water cannot meet the needs of irrigation, one must tap groundwater. It was probably at the beginning of the Ist millennium BC, in Persia or in neighbouring lands, that a remarkable device for obtaining high quality water was invented: the qanat.[80]

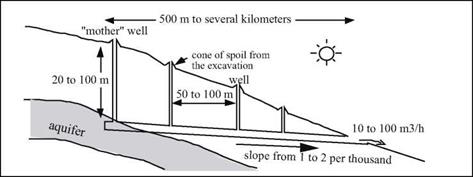

This word means “reed” in Akkadian. The device comprises a gallery, or shaft, dug nearly horizontally from the flank of a natural slope back into the aquifer, but with a small slope (of the order of one or two per thousand) so that the water can flow out by gravity (Figure 2.19). In general, the construction of a qanat begins with the drilling of what will become its terminal well, called the “mother well”, through which the nature and level of the water table can be determined. Then the excavation of the gallery begins from the downstream end, making it possible to work in the dry until the aquifer is reached; this excavation thus proceeds all the way to the mother well. Intermediate wells, normally spaced at from 50 to 100 meters, provide for removal of the spoil from

|

Figure 2.19 Principles of the qanat: a technique for mining groundwater, apparently first appeared in Urartu (Armenia) in the 8th century BC, and then spread throughout the Persian Empire (Goblot, 1979). |

the gallery, and provide for ventilation. The gallery can be several kilometers long, even reaching ten or more; the mother well can be the order of twenty to a hundred meters deep. The flow delivered by the qanat is generally from several, to several hundred, liters per second.

In 714 BC, Sargon II, king of Assyria (and the father of Sennacherib), is at war with king Rusa I of Urartu. He destroys the outposts of Urartu in the region of the lake of

Urmiah, as well as the qanats supplying water to the city of Ulhu, located to the east of this lake (60 km to the north of present-day Tabriz). The Assyrians, in a written account of this campaign, leave us an admirable description of the devices called “water outlets” that could comprise the first written evidence of the qanats:

“Ursa (i. e. Rusa) the king and lord of this land, pushed by his intelligence, showed his people how one manages the water outlets and creates a flow of water as copious as that of the Euphrates”.[81] [82] [83]

What is the genesis of this innovation? The Zagros mountains are a region of mines, especially in the area around the lake of Van. According to Henri Goblot, it was necessary to provide gravity drainage – to the surface – of certain mine shafts that were flooded after having pierced aquifers. In a country faced with the need to augment its water resources, the idea of making use of this drained water, and then to dig galleries expressly for this purpose, surely picked up speed rapidly. The idea had a grand future: the Persians adopted it to develop the Iranian plateau, and in particular to provide water for their capital, Ecbatane. This is reported by Ctesias of Cnidus, a doctor of Xenophon’s expedition who was long held captive by the Persians:

“Having arrived at Ecbatane, a city located in a plain, she (again the legendary Semiramis! Here, it can only be a Mede or Persian sovereign) built a luxurious palace and she watched over the entire region with great care. The city was without water and there were no springs

in the vicinity; but Semiramis brought water to all the city, abundant and very pure water

52

thanks to her heavy investments.”

Cyrus brought the technique of qanats to Oman, and Darius brought it to the oases of Egypt. As we will see in subsequent chapters, the Romans developed the technique in all of the Near East, and as far as Tunisia, and the Arabs took it to Spain and Morocco. Migrants coming from the East brought it to the benefit of Saharan oases.

Leave a reply