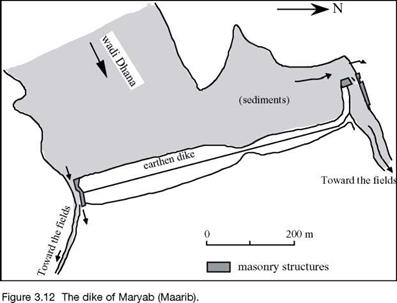

The oasis of Maryab; the great dike on the wadi Dhana

Maryab is the largest city of the region during the period of the sudarabic kingdoms. It occupies some 90 hectares enclosed by a 4.5 km wall. The site, apparently dating from the IInd millennium BC, is located some ten kilometers downstream of a gorge through which the wadi Dhana leaves the mountains. This wadi, typical of others in the region, has only occasional but particularly violent floods (twice a year, in April and July – August). Its flood flow can be as high as 600 m3/sec.

At first, partial diversions are employed to make use of water in the wadi, as is done throughout the region. Inscriptions from the 6th or 5th century BC mention the construction or rehabilitation of water intakes. As completed, these are massive installations of cut stone, from which emanate two irrigation canals that branch out to deliver water to two vast irrigation zones on either side of the course of the wadi. At an unknown date (perhaps prior to, or perhaps after the 5th century BC), the bed of the wadi is blocked by a large earth dam, 15 m high and 650 m long, with rock protection on its upstream face. The reason for this dam, which is unique in the region, is probably found in the continuously rising elevation of cultivated lands due to the deposition of sediments. The thickness of such deposits can reach 30 meters. One can imagine that the initial response to this increase in level is to move the intakes further upstream (there are remains of even older works downstream of the dam). But once the intakes had been moved all the way upstream to the narrow gorge from which the wadi Dhana emanates, the only solution became to raise the water level for the intakes by completely blocking the gorge.

In its final form, the irrigation infrastructure of Maryab is truly impressive.[134] [135] It includes a vast reservoir that, during floods, extends 4 km upstream of the dam. The intake at the north edge of the dam includes two passages, 3 and 3.5 m wide and 9 m high, that can be blocked by sliding beams into grooves carved into the massive stone

blocks. These passages lead to a sort of stilling basin, whose outlet supplies a 14 m wide canal that is 1,100 m long. This principal canal ends at a stone distribution basin fitted with numerous channels leading toward secondary canals.

At the southern extremity of the dam, an 80-m long masonry revetment, 11m high, protects the flank of the dike and borders the intake channel, 4.5 m wide. Here again, grooves are provided for controlling the water flow. This intake structure provides access to another narrower canal, as on the north side, but it is only 4 m wide.

On each of the two banks of the wadi, there is a side weir that permits overflow of excess water back into the channel (Figure 3.12). The two irrigated zones, covering some 5,700 hectares to the north and 3,750 to the south, comprise the “two gardens of Sheba”, veritable oases that will later be celebrated by Arab writers.

|

|

It is quite likely that the capacity of the two outlets ends up being insufficient during large floods, given the continuous deposit of sediments in the reservoir. The dam is probably damaged, and perhaps fails, by overtopping on several occasions. According to inscriptions, there was a rupture that was repaired in the middle of the 4th century BC, and major reconstructions in 456, 462, 549, and 558 BC.52 The definitive failure of the dam, occurring in the 6th century BC soon after the last reconstruction, is mentioned in the Koran:

“There was surely a sign in their country, for the people of Sheba: two gardens, to the right and left (that is to say on each side of the wadi). (…).

But they sidestepped this. Therefore we send against them the flooding of the Dam, and we changed their two gardens into two gardens of bitter fruits, tamarix and jujube trees.”-”

The city of Maryab cannot survive this catastrophe, and is abandoned. [136]

Leave a reply