The norias

The hydraulic noria, sometimes called the current noria, first appeared in the period of the Roman Empire. Herein we simply call this the noria. The very first evidence is found in the description of Vitruvius (around 25 BC) as we have cited in Chapter 6. Vitruvius describes the machine very clearly, but says nothing about the location of the particular device. Moreover we are not aware of any other mention of the noria by Roman writers. The second piece of evidence is found in the very heart of the land that will become the location of the largest norias: it is in a mosaic discovered at Apamea, a Hellenistic and Roman city located some fifty kilometers to the north of Hama opposite the depression of Gharb where the Orontes flows. We know from a signature that this mosaic dates from 469 AD. It is unusual to find machines represented in mosaics, suggesting that during this period the noria was considered to be an important element of the patrimony of the region. The tradition persists to this day, since even now the city of Hama maintains and renovates its norias. The accounts of Arab travelers in the 12th and 13th centuries, cited earlier in this chapter, speak of beautiful norias in the same breath as the Orontes and the city of Hama. Ibn Battuta, in the course of his grand voyage, observes norias at Amasya in Anatolia, on the Karan and the Fars, at Samarcand and even at the mouth of the Ganges. He mentions that they also can be found in China (but surely did not see them himself). As we have described earlier, norias are also

|

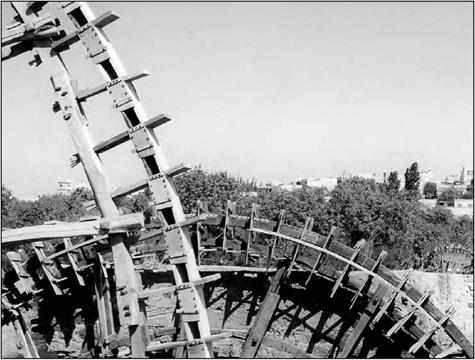

Figure 7.18 Detail of the wheel of the al-Damalik noria at Hama (note in particular the paddles and runnels). In the background is the wheel of the al-Hudura noria. (photo by the author). |

|

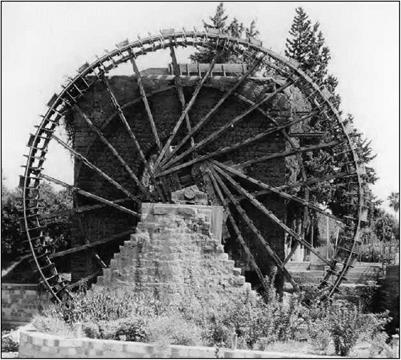

Figure 7.19 In the foreground, the axle of the noria al-Gisriyya at Hama; and in the background the noria of al-Mamuriyya, dating from 1453. Prior to its first reconstruction, this latter noria was the second largest in size (after the noria of al-Mohammadiyya). (Photo by the author). |

found in Andalusia (Toledo, Cordova) and at Fez. Still, in the eyes of these travelers, none of those norias are as remarkable as those found at Hama.

Norias are machines that can lift water to a great height, but they are also very expensive. They are thus best suited for implementation on rivers of fairly regular discharge, flowing in a well-defined course, and having rather steep banks – and at sites where gravity irrigation would be otherwise difficult. The norias of the Orontes have been particularly well studied.[362] The typical machine comprises a narrow wheel whose diameter depends on the desired lift. As is the case for its ancestor the lifting wheel, the noria has wooden water boxes or jars, on its perimeter to lift the water. The paddles are mounted on the outside circumference of the wheel; on the Orontes, these paddles are spaced at approximately 50 cm, whatever the diameter of the wheel. Rotation of the wheel is induced by the river current, channeled through a canal scarcely wider than the wheel itself and impinging on these paddles. On modest rivers such as the Orontes or the Khabur, an overflow dam raises the water level at the entrance to this canal, thus augmenting the speed of the current that drives the paddles.

The water boxes have an opening in the side (Figure 7.18). The boxes fill with water when they are immersed in the canal; then, when at the top of the rotation of the wheel, they pour their water out into a trough parallel to the wheel, at the top of the structure

|

Figure 7.20 Spoke structure of the noria al-Gisriyya at Hama (photo by the author). |

called the “tower”. The trough becomes an aqueduct that delivers the water to the distribution system. The tower and aqueduct are easily visible on Figure 7.7, as well as on the remains of the norias of Khabur (Figures 7.12 and 7.13). One end of the wooden axle of the noria rotates in a notch that is part of the tower; the other end rotates on a support that is, on the Orontes, a triangular masonry structure (this “triangle” is clearly recognizable in the mosaic at Apamea, see also Figure 7.19).

A single dam can accommodate several norias (Figure 7.8) and a single noria can moreover be fed by several supply canals (Figure 7.13), each dedicated to one wheel. If these wheels are of different diameter then each has its own outlet trough; if not, they can pour their water into the same trough. Often one can take advantage of the dam to install a mill as well (Figure 7.12).

One finds the largest known norias at Hama – those called al-Mohammadiyya and al-Mamuriyya, dating from 1361 and 1453. Their wheels are approximately 21 m in diameter. On rivers subject to destructive floods, for example the Euphrates, there is no need to bring excessive care and quality to the construction of the wheels as they are most often destroyed by the annual flood and thus must be rebuilt each year. On the other hand on the Orontes, a river of quite regular flows, the wheels are built with great care. Large and narrow, they are trued to an astonishing precision (several centimeters on wheels from 10 to 20 m in diameter). They are serviced each year at the end of the irrigation season. Their wooden arms are not radial, but are laid out in an arrangement that is common to all the wheels, but particularly those of the Orontes, an arrangement that is clearly visible on Figure 7.20.

Leave a reply