The Nilometers

One can readily see that in Egypt, measurement of the flood level has great importance. The management of the irrigation system is based on such measurements, as are the taxes, since the agricultural yield can be deduced almost automatically from the flood level. The level is quantified using graduated scales carved into stone; Strabo calls these [87] [88]

|

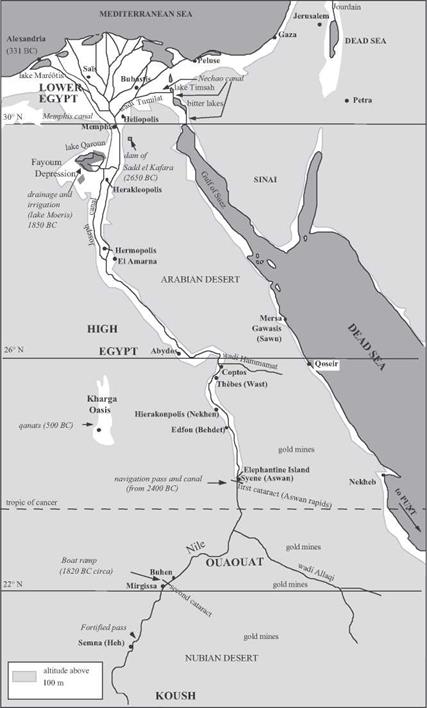

Figure 3.1 Major hydraulic works in ancient Egypt and Nubia. |

scales “nilometers”. The most well-known nilometers[89] are those at the fortified pass of Semma, upstream of the second cataract (around 1800 BC), on Elephantine Island at Aswan, downstream of the first cataract (1800 BC), at the temple of Karnak at Thebes (800 BC), and near Memphis upstream of the delta (Figure 3.1). But much older nilometers surely existed, since flood levels were reported in the annals of the IVth and Vth dynasties (2500 – 2000 BC).[90] The unit of measurement is the nilometric cubit, or 0.525 m. The zero, or datum, of the nilometric scales is quite probably set at the low-flow level of the river, a level that can vary over time as the width of the river varies (a scale change occurred about 2000 BC). The scales have marks that correspond to favorable flood levels: a little more than 21 cubits at Elephantine, 12 to 14 cubits at Memphis, 7 cubits in the delta.

There are two particularly important locations for flood measurement: at

Elephantine (Aswan), the point of entry of the flood into Egypt proper, and at Memphis,

|

Figure 3.2 The Nile between Thebes and Aswan (photo by the author). One can see the contrast between the green irrigated plain (dark in the photo) and the arid hills in the background. |

sentinel of the flood that will appear on the delta. In fact there are two nilometers at Aswan. According to tradition, a precise water level at Aswan is obtained in a well connected to the river, to dampen fluctuations caused by waves in the river itself. The date

of this concept is unknown. Let’s again listen to Strabo:

“The nilometer is a well, built of stone quarried from the banks of the Nile itself, in which there are marks indicating the greatest floods of the Nile, the smallest, and the average, for the water level in the wells rises and falls with that of the river. This is why there are marks on the walls of the wells, showing the peak flood levels and other levels. Inspectors examine the wells and communicate their observations to the rest of the population, for their information; they know well in advance, from these indications and their times, when the future inundation will occur, and can announce these forecasts. This information is useful not only to the farmers for the regulation of water distribution, for the dikes, the canals, and things of this nature, but also to the prefects for the estimation of public revenue, for these revenues increase with the strength of the flood.”[91]

According to Daniele Bonneau, the measurements begin at the end of June, at the summer solstice, and continue through the period of inundation to the end of October, and are made known throughout the valley for general public use.

Of course the Nile is also the principal “highway” of the country. The paintings of boats of the Nile found on protohistorical pottery are among the first such known depictions. Each city, each temple, has its fluvial port, generally constructed in the form of a “T”, with a basin connected to the Nile by a short canal.

Leave a reply