The irrigation system in the Min valley, Sechuan

In 316 BC the Qin occupy the land of Shu, in the southwest, as far as the middle course of the Yangtze river. They developed the basin of the Min River, a tributary of the Yangtze in the Sechuan depression. In the region of present-day Chengdu, they implement a gigantic program of irrigation works. Sima Qian mentions this project – all too briefly:

“In Shu, Li Bing, the governor of Shu, cuts back the Li Escarpment to control the ravages of

the Mo (Min?) River and also opened up channels for the Two Rivers through the region of 33

Chengdu.”

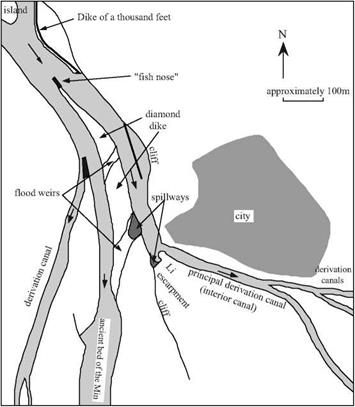

The crown jewel of this project is a remarkable intake structure on the Min (Figure 8.4),[398] near the city of Dujiangyan (earlier Guanseian). It includes a main dike (the dike of a thousand feet) that directs the current toward a structure built of large stone blocks, called the fish nose, that divides the river flow into two portions. The resulting two main channels are separated by the diamond dike whose crest is above the level of the floods, then by overflow structures that make it possible to spill floodwaters from the left channel (whose bed is higher) toward the right channel, which occupies the ancient river bed.

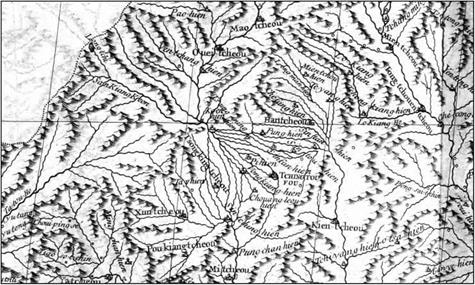

The left channel, or interior channel, is cut into rock across the hill that is some sixty meters in height, and on which the city of Dujiangyan is situated. Sima Qian speaks of the part of this hill that is isolated by the cut called the escarpment of Li. Further downstream, along this same channel, numerous intake structures direct irrigation water toward Chengdu and the plain of Sechuan (Figure 8.5).

|

|

It was surely Li Bing, the designer of the project, who also planned for its maintenance. During the low-water period from mid-October to the end of March the canals are cleaned out and the heights of weirs and dikes are brought back to their original levels. This maintenance requires that the two arms of the river be alternately dewatered with portable wood dams. In addition at regular intervals the fish nose, the main struc-

ture separating the two channels, is maintained.

Li Biing, along with his son who finished these works, is viewed as a benefactor by the inhabitants of the region. He becomes immortal; at the very top of the escarpment of Li, a Taoist temple is consecrated to him.

|

Figure 8.5 The irrigation canals of the Chengdu region, detail from a map established by the Jesuits of the 18th century (Du Halde, 1735 – ancient archives of ENPC). |

Leave a reply