The Indus and the Harappa civilization Bactria and the Margiana, on the banks of the Oxus

It is somewhat frustrating to write of the great civilization of the Indus Valley. Its origins, near the beginning of the IIIrd millennium BC, are unknown; and the reasons for its demise, a thousand years later, hardly less so. What is known results from archaeological digs at the two large sites of the twin cities Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro. The civilization is thought to be the country called Meluha. The towns of the Indus civilization are built on terraces raised above the flood level, their perimeters protected from erosion by brick structures. One of the most notable aspects of these towns is, as we will see later, the large number of wells and the integrated water use in the housing, including wastewater drainage. The writing of the Indus civilization has not yet been deciphered. The civilization had maritime trade with Sumer, the two cultures having some elements in common.

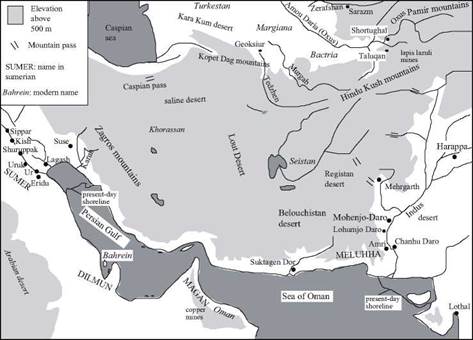

It is known that there were also land links in this period between the Indus civilization and Mesopotamia, passing to the north by Bactria and the Caspian Sea, supporting the trade in lapis lazuli (a semi-precious stone).[15] Indeed, at Shortughai, in the eastern portions of the Oxus basin (present-day Amou Daria) the remains of a substantial establishment of Harappean culture have been found. Here, in the middle of the IIIrd millennium BC, extensive irrigation was practiced, as evidenced by 25-km long canals (see

Figures 2.20 and 7.2). Moreover, Harappean relics have been found in towns that flourished to the west in the same period, such as Altyn, proof of long-distance commerce. Should one then consider the Indus as the origin of irrigated agriculture, key to the subsequent prosperity of central Asia, whereas conventional wisdom considers Mesopotamia to be the origin? The answer is not simple.

In the VIIth or VIth millennium BC the Neolithic revolution reached the regions to the southeast of the Caspian Sea, to the plains where the Gorgan and Atrek rivers flow, and to the foothills of the Kopet Dag mountains (Figure 1.3). The Jeitun culture that developed at the foot of these mountains had already likely developed modest irrigation, even if there is no formal proof of this. Somewhat later, population increase led to new

|

Figure 1.3 From Sumer to the sites of the Indus Valley (Harappa civilization), and the Oxus Civilization, c. 2500 – 2200 BC. The oasis of Geoksiur is shown because of its importance to the history of irrigation, but its settlement dates from much earlier (5th and 4th millennia BC) |

settlements to the east, first where the Tedzhen River forms a branched delta that vanishes into the desert of Kara Kum, in the Geoksiur oasis. Artificial irrigation appears in this oasis during the IVth millennium BC. Russian archaeologists have studied derivation canals extending perpendicular to the Tedzhen. These canals are 3 – 5 m wide, 0.8 – 1.2 m deep, and can be identified along a distance of 3 km. It is interesting to note, moreover, that the most active of this irrigation activity, supposedly the first to occur outside of Mesopotamia, apparently coincides with the concentration of population into a single site of the oasis. The settlements had previously been dispersed around the oasis, suggesting that the irrigation efforts were a response to the gradual weakening of the water supply, a prelude to complete abandonment of the oasis. The neighboring cities of Namagza and Altyn, whose existence would be inconceivable without intensive irrigation, surely were the destinations of the dislocated peoples. This culture and its techniques, conveniently called the Oxus civilization, come together later in the IIIrd and IInd millennia BC in all of the Bactria-Margiana region. Traces of this civilization have even been found to the north at Sarazm, on the Zeravchan River (later to become the sites of Boukhara and Samarcand).[16]

Despite the decline of urbanization in central Asia, including the disappearance of the cities of Altyn and Namagza in about 2200 BC, the destiny of Bactria and Margiana is to remain civilized, an obligatory passageway between Mesopotamia and the Far East. The destiny of the large cities of the Indus, on the other hand, is to vanish forever. After several centuries of existence, they become uninhabited, for reasons unknown. Around 1750 BC, Harappa is destroyed, and Mohenjo Daro is abandoned.

Leave a reply