The great aqueducts of Roman cities

Water is at the very top of the scale of values of Roman civilization. Water “not only services and satisfies the needs of the public, but also satisfies their pleasures.”[213] Numerous public fountains flow constantly in the city of Rome. Some individual users are granted a special concession for drawing water. Under the Republic this service is paid for, and it later becomes a free service granted by the Emperor. But the thermal baths, becoming widespread from the period of Augustus, are the most important water users.

|

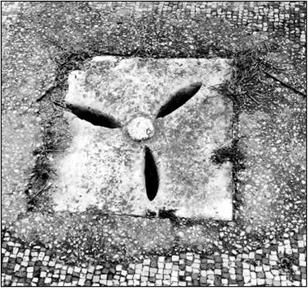

Figure 6.2 A Roman public fountain at Ostia (photo by the author) |

When water is in short supply, basic needs (e. g. public fountains, and flushing of sewers to maintain hygiene) must take priority over pleasure use. The architect Vitruvius describes a design giving priority to the public fountains (see Figure 6.4):

When they (the channels) are brought home to the walls of the city a reservoir (castellum) is built, with a triple cistern attached to it to receive the water. In the reservoir are three cisterns of equal sizes, and so connected that when the water overflows on either side, it is discharged into the middle cistern, in which are placed pipes for the supply of the public fountains; in the second those for the supply of the baths, thus affording a yearly revenue to the people; in the third, those for the supply of private houses. This is to be so managed that the water for public use may never be deficient.”[214]

There remain only a few traces of the Roman distribution networks, one of the few being at Pompeii (Figure 6.3) whose castellum corresponds rather well to the scheme described by Vitruvius.[215]

|

Figure 6.3 Water in a Roman city, Pompeii. The Figure shows the map of public fountains, the layout of water supply to public monuments and the intermediate works in the various circuits: elevated reservoirs and distribution towers. The distribution towers are fitted with a small elevated reservoir, whose level makes it possible to adjust the pressure in the downstream installations. The castellum of the Vesuvius gate (Figure 6.4) is situated at the highest point of the city, receiving its water from the aqueduct of Serino (Escheback, 1979-1983). In August 79 AD Pompeii is destroyed by an eruption of Vesuvius.

|

water passes over barriers of different elevations:

|

Figure 6.4 Castellum schematic at the Vesuvius gate of Pompeii, terminal point of the aqueduct, feeding the three distribution circuits. Water to these three circuits is supplied by overflow weirs at different levels, thus providing for a distribution hierarchy as recommended by Vitruvius.

|

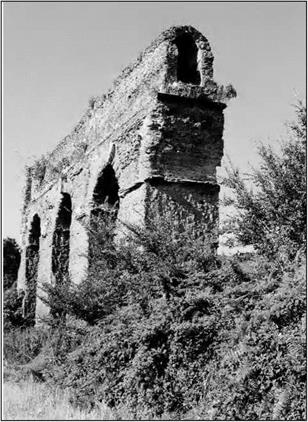

Figure 6.6 The Anio Novus, one of the greatest Roman aqueducts, supported by arches in the Anio valley, between Tivoli and Castel madama. The canal, still lined with opus signinum, is well conserved. This aqueduct was built in 52 AD near the end of the reign of emperor Claudius (who also was responsible for the Aqua Claudia aqueduct), and is some 87 km long. It carries water captured from the Anio river, in the Sabine mountains near Subiaco.

Figure 6.6 The Anio Novus, one of the greatest Roman aqueducts, supported by arches in the Anio valley, between Tivoli and Castel madama. The canal, still lined with opus signinum, is well conserved. This aqueduct was built in 52 AD near the end of the reign of emperor Claudius (who also was responsible for the Aqua Claudia aqueduct), and is some 87 km long. It carries water captured from the Anio river, in the Sabine mountains near Subiaco.

(photo by the author).

As we can see through these examples, Roman cities benefit from an abundance of water, a bounty unequalled until the 20th century AD. Creation of this abundance requires that water be brought to the cities from springs or other supply points, where in general a storage reservoir is built, serving also as a settling or clarifying basin. The water is conveyed by aqueducts to the city’s castellum, or water tower, from which emanate the local distribution circuits. The aqueducts are often lasting monuments in which the Romans take great pride. A highly placed Roman official, whom we introduce later on, even compares these aqueducts to the Pyramids and to Greek temples:

“With such an array of indispensable structures carrying so many waters, compare, if you will, the idle Pyramids or the useless, though famous, works of the Greeks!”[216]

Leave a reply