The Grand Canal

The Grand Canal of the Sui, the Tang, and the Song (6th to 11th century)

In 581 AD, Yang Jian founded the Sui Dynasty at Chang’an. He reunifies China in 589, and in 604 the country sees its new master enthroned as emperor. An imperial necessity appears immediately: to establish a safe communication route between the north of China where the reconstructed capital Chang’an is located, and the Yangtze basin to the south. This need reflects a fundamental change in the relations between north and south

|

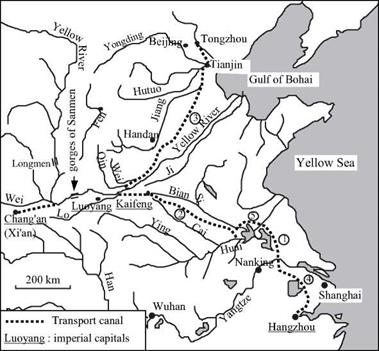

Figure 8.12 The Grand Canal of the Sui, the Tang and the Song. 1. Shanyang traverse (renovated in 587) 2. Tongji canal (605) 3. Yongji canal (608) 4. Jiangnan canal (610) 5. Northern detour of Hongze lake (about 735) |

since the Han period. The north was inflicted with a series of wars and barbarian invasions, whereas the lower basin of the Yangtze had begun to develop, propelled by the rapid growth of rice cultivation. The cities of the lower Yangtze, where Chinese intellectuals took refuge, had become the cultural centers of the land. The communication route therefore had high political and economic stakes: cementing the unity of the country and, at the same time, generating tax revenues.

In 587, even before the fall of Nanjing, Yang had restored the canal that connected the Huai and the Yangtze. The ancient Han canal had filled this role in olden times, and its course had already been shortened in 350. The north branch of the old 4th or 5th century Hong canal had linked the Huai to the capital region. But this canal, subsequently called the Bian canal (or Pien), had become clogged with sand. It was decided to conserve the approximate original layout to the west of Kaifeng, but then to depart from the Bian River in cutting more to the south to end up on the Huai to the west of the present – day Hongze lake.[428] Since the emperor wanted to proceed quickly, he acted radically. He mobilized five million people, men and women alike, to dig 1,100 km of this new sixty-meter wide canal in just five months. The new canal is called the Tongji.

The next step involved renovating the communication route toward the north for essentially strategic reasons. Indeed, the threats of barbarian invasions were from the northeast, and there were also plans for a military incursion into Korea. The Yongji canal, some 1,000 km long, is finished in 608. This canal is at first a derivation of water from the Qin (a river that flows into the Yellow River a little downstream of Luoyang), but later ends up connecting to another small river oriented toward the north, and called the Wei (this is not the large Wei that is near Chang’an). This river then joins the Jiang (that occupies the course of the Yellow River prior to 602 BC) near Tianjin. Two years later in 610 the new Jiangnan canal links the Yangtze to the port of Hangzhou to the south. These works are completed with an access canal to the newly reconstructed city of Luoyang (which becomes a second capital) as well as by a complete renovation of the old canal that links Chang’an to a bend of the Yellow River. The ensemble constitutes the first Grand Canal in the form of a gigantic Y with the capital at its base. For four centuries this will be the spinal column of the empire.

But these massive projects exhausted the population, and there are floods in the Shandong. Moreover Emperor Yang suffers several military reverses at the hands of the barbarians. In 618 he is eliminated and immediately replaced by the Tang Dynasty under which China enjoys a sort of golden age for two centuries. Chang’an, the capital and terminus of the Silk Road, becomes a cosmopolitan city in this period. Around 700 the last Sassanide Persian sovereign comes to Chang’an to finish his life in exile. Canton is inhabited by numerous Arab merchants.

The Grand Canal is of course maintained and further developed. A derivation to the north of the present Hongze lake in 735 allows southbound boats to bypass the rapids of the Huai. Management of the canals is facilitated by the construction of gates near their outlets into the large rivers; dikes and rockfill protect the canals at vulnerable locations. In this period some 165,000 tons of grain are carried annually on the Grand Canal; it is under the Tang that the blossoming of rice cultivation in the Yangtze basin is the most pronounced. Immense granaries are built at the nodal points of the navigable waterway system.

The gorges of Sanmen remain troublesome for navigation as far as Chang’an. The rapids are dangerous and the channel contains dangerous rocks. From 733 a roadway was used to transport merchandise over a land detour of several kilometers. But in 741 a new 300-m long canal was dug through solid rock to cut across the river bend having the most dangerous rapids. In the south, the magic canal is improved in 825, as we have seen earlier, and then again in 868.

Between 960 and 1127 the Song set up their capital at Kaifeng (called Bianling at this period). Since ancient times Kaifeng, along with the old Hong canal, had been an important communication node, not far from the junction of the two branches of the Y of the Grand Canal. The Bian, tributary of the Si, flows naturally into the Tongji canal whereas the Cai, flowing toward the south, connects to the Tongji through a canal called the Huimin. In 1071 major work is done to redo the connection between the Yellow River and the Tongji canal.[429] The entire Song period is marked by a very important expansion of navigation on the large rivers and along the coasts.

Leave a reply