The Grand Canal of the Yuan and the Ming Dynasties

In 1126 the Song were forced to abandon the north of China, pushed out by barbarians who had partially adopted Chinese culture (the Jurchen, or Jin). During their retreat the Song destroy the south-bank dike of the Yellow River in the Kaifeng region, and this causes considerable damage to the Tongji canal and destabilizes the river. For more than three centuries after this the Yellow River will tend to form multiple and unstable branches. Pushed to the south, the Song further destroy hydraulic infrastructure and set up their capital at Hangzhou, at the southern extremity of the Grand Canal. During the period of wars that follows, in about 1190,[432] the river starts to migrate toward the south (Figure 8.2). From this date, part of the discharge in effect bifurcates toward the Huai (note this had already occurred between 132 and 109 BC). First the floodwaters, then the Mongols of Ghenghis Khan, sweep over China. From 1214 to 1276 the Mongols destroy the Jurchen powers, then those of the Song. Their first undertaking is to massacre all the inhabitants, as in Mesopotamia. But in 1271 they take on a more noble role and, under the name of the Yuan Dynasty, reign over an immense empire that extends from the Sea of China to the Euphrates.

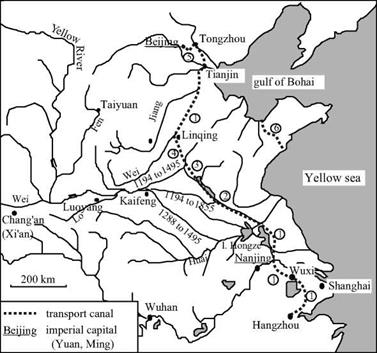

The Yuan chose Beijing for their capital, this being a more central site for their new empire than the ancient capitals of Chang’an, Luoyang and Kaifeng. Just as the Sui had been impelled to construct the first Grand Canal in the 7th century, the Mongols now saw the need to reestablish a large waterway, ideally as a more direct link from Beijing to the Yangtze basin. In 1275 a Mongol general called Bayan was fighting against the Song of the south. He began studies of a canal that would use the north portion of the Grand Canal of the Sui, but would cut directly toward the southeast from Lingqing. This canal would rejoin the arm of the Yellow River that had bifurcated from there toward the Huai since the 1190s (this is course no. 5 in Figure 8.2). Between 1280 and 1283 the Huangong and Jizhou canals were built more or less along the alignment of this arm.

The Jizhou canal takes a shortcut across the foothills of Shandong, and has 31 gates along a distance of nearly 150 kilometers (250 li). These canals make it possible to ship goods from the south up to the bifurcation of the course of the Yellow River, then on the

|

Figure 8.13 The Grand Canal of the Yuan and the Ming. 1: elements of the Grand Canal of the Sui (renovated between 1280 and 1290) 2: Huangong canal (1280) 3: Jizhou canal (1283, 1411) 4: Huitong canal (1289) 5: Tonghui canal (1293) 6: Jiao-Lai canal |

northern course to the Gulf of Bohai from which they continue by sea to Tientsin.

Five years later (1288) the Yellow River abandons its principle course to the north of Shandong (though this branch carries some flow until 1945) and flows out to the south into the Huai, even further upstream than earlier. This course change probably motivated and likely facilitated the completion of the waterway project. Indeed just one year later, in 1289, the Huitong canal – whose design had been studied by general Bayan – is completed in its turn. The totality of the project is completed in 1293 by the Tonghui canal linking the capital Beijing to Tongzhou. This canal had to have some 20 gates, for Beijing is at a higher elevation than the rest of the system. The remainder of the waterway network, whose layout follows that of the first Grand Canal of the Sui and the Song, is simply brought back into service and improved (in 1290 for the channelization of the Wei river.).

Marco Polo sojourns in the court of Kubla Khan in 1280, and probably in 1288-1290 is sent on a mission to the south of China (he returns to Italy in 1298). He writes of the city of Guazhou, at the junction of the Yangtze and the Grand Canal, as follows:

“The city is on the river, and it is there that, every year, vast quantities of rice are collected.

And, from this city, they are transported to the large city of Cambaluc (Beijing), to the court of the Great Khan, by water. But understand this is not by sea, but by rivers and lakes. [….] And I tell you that the Great Khan had these waterways between the two cities brought into service, for he had huge trenches dug, very wide and very deep, from one river to another and one lake to another, and had water transported by canals, so that it all became like one large river, and great ships go on it.”[433]

Marco Polo also speaks of the city of Jining, which is at the junction of the Huangong and Jizhou canals. He notes how the watercourses coming from the heights of Shandong are captured to supply the highest portions of the Canal:

“And I tell you further that they have a river from which they profit immensely and I will tell you how. The truth is that this large river comes from the midlands to this city of Singi Matu (Jining), and the people of the city, from this large river made two; for they sent half toward the rising sun and the other half toward the setting sun, that is to say that one goes toward Mangi (the region of the lower Yangtze) and the other toward the Catai (the region of Beijing). And I tell you truthfully that this city has such grand ships – such a large quantity of boats – that no one could believe it without having seen it. Do not take this to mean that they are large ships: they are of appropriate size for vast rivers. And I tell you that these ships carry to Catai and to Mangi such large masses of merchandise that it is a marvel… .”[434]

Starting in 1327, repeated floods cause serious famines. In 1344, the dikes break downstream of Kaifeng and are not restored until 1349. The plight of the miserable peasants of this region, along with the massive labor conscriptions necessary for the dike repairs, leads to the emergence of the Red Turbans. This secret society soon leads an insurrection against the power of the Mongols.[435]

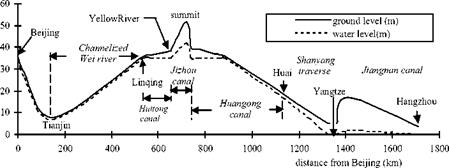

A glance at Figure 8.14 makes it easy to understand the problem of water supply to

|

Figure 8.14 Longitudinal profile of the Grand Canal, from a modern survey (Needham et al, 1971). |

the highest portion of the Grand Canal of the Yuans, i. e. the Jizhou canal in Shandong.

This problem is not solved by the Yuan, who continue to use primarily the maritime route and in effect cut off the Shandong peninsula with the Jiao-Lai canal. It is not until the Ming regime, arising from the insurrection that chased out the Mongols in 1368, that an effective solution to this problem is developed using hydraulic works. In 1411,

165,0 people are put to work on the 200-day construction of a dam-reservoir that could assure a sufficient supply of water to maintain the supply to the Jizhou canal throughout the year. Other small reservoirs are constructed near the canal’s locks, which were also rebuilt at this time.

Under the Ming the strategy adopted for control of the Yellow River consisted in preventing any return of the course toward the north through construction of a very long dike, stretching for several hundreds of kilometers. Systems of multiple dikes delimiting the flood plain were also constructed. A real strategy for sediment management was put into place. This strategy combined deposition in flood-plain zones managed for this purpose with narrower channels in which the strength of the current was sufficient to prevent deposition. Starting in 1495 the course of the river was finally stabilized, as shown on course no. 7 of Figure 8.2.

Important canal rehabilitation work took place in 1528, still under the Ming, in particular separating the bed of the Grand Canal from that of the Yellow River. Piracy was developing along the shores of the Sea of China at this time, rendering more indispensable than ever the use of the grand artery between the south and north of the country.

It was also during this period that work was done on the Hongze lake. This lake had probably been just a natural flood plain for the southern course of the Yellow River up to then. This zone was transformed into a permanent reservoir of increased volume through construction of a large north-south dike delimiting the eastern bank of the lake over more than 30 km, in 1578.[436] An engineer called Pai Jixun led this work; he was also known for his work on control of Yellow River sediments. At the beginning of the Manchu domination (1660) this dike is extended to a total length of 67 km and its height is raised 1.5 m to attain a maximum of 7 m. The structure itself is a masonry wall whose stones are tied together by steel tendrils. The wall is about 1 m thick and supported by an earthen embankment, and rests on a foundation of piles.

In the 14th and 15th centuries the Grand Canal evolves to a configuration that is essentially the same as today. Its total length of about 1,700 km makes it the largest hydraulic project ever constructed by man. We earlier saw how travelers at the beginning of the 14th century had been impressed by the Grand Canal of the Yuan. Three centuries later another westerner embarks upon the Grand Canal. This is father Matteo Ricci, the founder of the Jesuit missions in China, who traveled from Nanjing to Beijing between September 1597 and February 1598. Being a scientist, he begins by describing the overall fluvial system:

“This river of Nanjing (the Yangtze) goes from Nanjing to the north; then, returning somewhat toward the midlands, flows with great impetuosity into the sea. [….] This is why, to be able to go by water into the royal court of Beijing, the kings of China drew a large canal from this river to another, that is called Yellow. [….] This river [….] as if in revenge for the hate that the Chinese carry to foreigners, very often spoils a large part of the kingdom through its large floods and changes its channel as it pleases, when it is filled with sand that it carries along.”[437]

This latter account reveals the isolationism that characterizes the end of the Ming Dynasty. In following sections of his treatise Matteo Ricci gives a very vivid description of the traffic on the upper portions of the Grand Canal, as well as of passages through the flush locks. He also mentions the inclined planes on which boats are dragged using capstans. He does not mention any chamber locks.

“And, however, the multitude of vessels is so excessive that the ships, each blocking the others, are often obliged to wait several days to pass, principally in certain times when there is not enough water in the canals. To solve this, they hold back water in several places with locks of wood, which also, to serve two purposes, are installed as bridges. These locks, when the stream is full, are opened and the boats are carried by the force of the running water. And, thus, the sailors navigate from lock to lock with great difficulty and along a tiresomely long route. The work is made even more difficult since it is very infrequent that, in the narrow strait of the stream, the winds are favorable for the vessels. This is why, ordinarily one uses ropes to advance along the canal and even, it often happens that at the entrance or exit from the locks, when waves rising up like impetuous whirlwinds come to envelope the boats, they are lost in the canals drowning all those who were within. But the ships of magistrates or principals are pulled against the water with machines of wood; and this happens along all the route at the expense of the King.”[438]

Reading this account, one can understand what led Chiao Wei-Ho to invent the chamber lock in the 10th century. It is more difficult to understand why this process is not used in the upper reaches of the Grand Canal of the Yuan and the Ming. Does this

|

Figure 8.15 An ancient stretch of the Grand Canal (Jiangnan canal) at Wuxi (photo by the author) |

perhaps mark the beginning of the decline in the spirit of innovation that will characterize the 17th and 18th centuries?

This is a good time to note the influence of inland water transport on urbanism. Certain cities along the Grand Canal are virtual “Chinese Venices” (Figure 8.16). We can illustrate this through the Venetian Marco Polo’s description of the city of Hangzhou (Han-Tcheou). In the 13th century this city becomes the capital of the Song when they retreat to the south. With nearly one and a half million inhabitants,[439] it is also perhaps the largest city in the world (along with Baghdad before the passage of the Mongols): “It (the city of Hangzhou) is situated in such a manner that it has, on one side, a freshwater lake that is very clear, and, on the other side, an enormous river that, entering in many canals from small to large and flowing through all the districts of the city, carries all the filth, then penetrates into the lake and, from there, flows toward the ocean. This makes the air very healthy. One can visit all the city both on land and on the water. The streets and canals are long and wide, so much so that boats can navigate on them as they please. [….] No one should be surprised to see so many bridges; because I tell you that this city is entirely on the water and surrounded by water. [….] On the other side of the city is a trench that is perhaps forty milles in length, enclosing the city on that side; it is very wide and completely full of water from the aforementioned river. This was done by order of the ancient kings of the province, to be able to redirect the river each time it overflows the dikes.”[440]

Leave a reply