The Cretan cities and palaces: urban hydraulics brought to perfection

Crete was inhabited by migration from Anatolia, probably at the end of the VIIth millennium BC. Its more highly developed civilization, the Minoan, dates from about 2100 BC. This maritime empire was apparently a peaceful one, since neither palaces nor cities were fortified – and this despite the threatening face of the monster that the legendary king Minos kept in his labyrinth according to the Greek legends of Theseus and Minotaur.[138] A creative and sophisticated urban and palatial architecture characterizes this civilization. The Egyptians know the Cretans as the Keftious, and Mesopotamians know them as the Kaptaras. The Cretans could not have been ignorant of the Eastern developments in urbanism and urban hydraulics, because at the same time northern Syria is experiencing the “belle epoch” of Mari (destroyed in 1761 BC), Elba (destroyed around 1600 BC, and Ugarit (destroyed about 1200 BC).

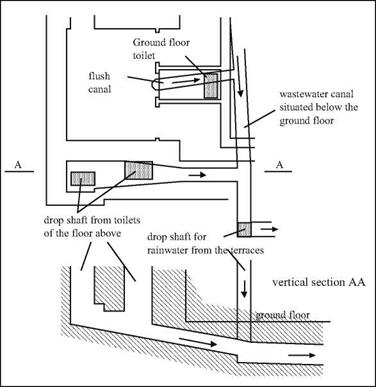

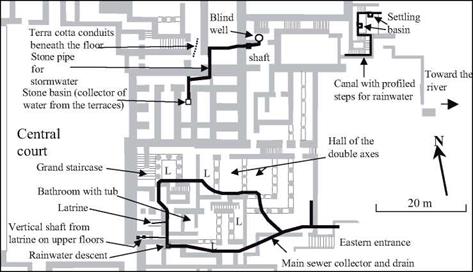

The remains of numerous cities have been found in Crete, as well as the remnants of four great “palaces” (or temples?): Knossos, Phaistos, Mallia, and Zakro. These cities and palaces have ample water supplies.[139] In the palace of Knossos, the largest in Crete, there are bathing rooms, latrines, and drains (Figure 4.4). These latrines have a “flushing” channel, dug into the floor, that is fed by an outside reservoir (Figure 4.3) and a sort of siphon, in an alcove of the back wall, connected to the drain. The bathing rooms have portable terra cotta bathtubs that can be arranged so that one can pour water over the bather from a separate room. Systems such as this, albeit of various degrees of sophistication, can be found in the other palaces on the island. For example, the guest quarters of Knossos include a room where voyagers can wash their feet in running water.

|

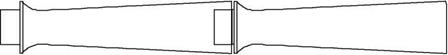

Figure 4.2 Elements of a Minoan terra cotta pipeline (after Graham, 1987). |

|

Figure 4.3 Drainage of rainwater and wastewater, discovered in the east wing of the Knossos palace (Castleden, 1990). This area is at the lower left in Figure 4.4, which shows the overall layout of the eastern wing (see “latrine”). |

But where does all this water come from? For Knossos, it is quite probably from a spring some 15 kilometers away. Terra cotta pipes following the natural slope of the land bring water first to the guest quarters, and then beyond to the palace. The pipeline crosses a small river on a little bridge that provides access to the palace from the guest quarters.[140]

These Cretan aqueducts are, as far as we know, the first true water supply works. They were surely made of terra cotta conduits, and laid along the natural slope of the land, as were the later Greek aqueducts. And actual remains of terra cotta pipelines assembled from conical sections (Figure 4.2), that can fit into each other using flanged joints, have been found in Minoan palaces.[141]

Cretan urbanism is also remarkable for the way it uses rainfall runoff for sanitary purposes. In the palace of Knossos (Figure 4.4), Arthur Evans has identified laundries located at the eastern extremity of the palace. These laundries are apparently supplied by a pipe that descends along a stairway, bringing water from a basin where runoff from

|

Figure 4.4 Hydraulic features identified in the eastern wing of the palace of Knossos. L = light well |

the terraces is collected and stored.

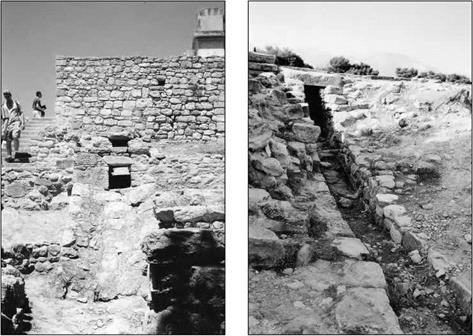

In Knossos there are wastewater drainage systems, and the use of these same pipes for storm drainage further contributes to urban hygiene. Arthur Evans found two independent sewage networks in his excavations. One is made of terra cotta pipes, canals, and large collectors; the other uses smaller underground conduits. The system is serviced through manholes, and these manholes also capture rainfall runoff. Excavations directed by Nicolas Platon at Zakro have uncovered stone or terra cotta gutters under the floors, as well as masonry conduits covered with stone slabs. In the city of Palaikastro,[142] researchers have uncovered traces of stone gutters used to drain wastewater from houses, dumping the waste into the main sewer that flows under the central street. There is an analogous system of sewers in the Minoan city of Akrotiri on the island of Thera, buried around 1520 BC by the explosion of the volcano of Santorin.[143] Remnants of control gates have been found at several of these sites.

The elaborate drainage systems of Crete mirror similar developments at other sites of the IVth and IIIrd millennia BC, such as Habuba Kebira and Mari on the Euphrates, Harapa and Mohenjo Daro on the Indus. It seems reasonable to suppose that the Minoan engineers were inspired by oriental concepts of drainage networks. It is, however, only in Crete that these networks are developed and generalized to the point that we have seen above. But as for the capturing and distribution of water for domestic supply, we are not aware of other examples in the orient prior to the Ist millennium BC. Therefore this was very likely a Cretan innovation.

Hydraulic works were also developed in support of agriculture. A canal network was constructed on the plateau of Lassithi, south of Mallia, for the drainage or irrigation of cultivated land. Recent detailed exploration of the region of Mallia, between 1989 and 1995, shows that the coastal plain was very actively cultivated in this period, in sufficient measure to feed the inhabitants of the 60 hectares of urbanized land around the palace. Gutters deliver water diverted from mountain streams to the fields through temporary storage in cisterns that are dug into the tops of hills.[144]

|

Figure 4.5. Outlets of the principal collectors of two Minoan palaces (photos by the author): – left, near the east entry of the Knossos palace; right, south of the Phaestos palace (under the large central court). |

The Cretan palaces are destroyed several times by earthquakes, and then reconstructed. But the palaces, and the brilliant civilization of the island, come to an abrupt end about 1400 BC. The causes are not precisely known. It is possible that the explosion of the volcanic island of Thera (Santorin) caused an ecologic catastrophe when it covered part of the island with cinders, and that a tidal wave destroyed the island’s northern settlements. The bellicose Mycenaeans of continental Greece were also responsible for destruction of the palaces, symbols of the Minoan civilization. Only the Knossos palace survived for some time as the weakened seat of a power that seems now to have been Mycenaen.

These cataclysms, the explosion of Thera, the disappearance of Akrotiri, the abrupt end of Minoan commerce, are all probably the source of the legend of Atlantis, reported by Plato (427 – 347 BC) from Egyptian sources.[145] In any case, when he speaks of Atlantis, Plato gives tribute to the hydraulic developments of this legendary island, recognizing both urban hydraulics and irrigation as shown in the following significant extract:

“I will now describe the plain, as it was fashioned by nature and by the labours of many generations of kings through long ages. It was for the most part rectangular and oblong, and where falling out of the straight line followed the circular ditch. The depth, and width, and length of this ditch were incredible, and gave the impression that a work of such extent, in addition to so many others, could never have been artificial. Nevertheless I must say what I was told. It was excavated to the depth of a hundred, feet, and its breadth was a stadium everywhere; it was carried round the whole of the plain, and was ten thousand stadia in length. It received the streams which came down from the mountains, and winding round the plain and meeting at the city, was there let off into the sea. Further inland, likewise, straight canals of a hundred feet in width were cut from it through the plain, and again let off into the ditch leading to the sea: these canals were at intervals of a hundred stadia, and by them they brought down the wood from the mountains to the city, and conveyed the fruits of the earth in ships, cutting transverse passages from one canal into another, and to the city.”[146] [147]

Or again, this reference to the water supply:

“In the next place, they had fountains, one of cold and another of hot water, in gracious plenty flowing; and they were wonderfully adapted for use by reason of the pleasantness and excellence of their waters. Of the water which ran off they carried some to the grove of Poseidon (…) while the remainder was conveyed by aqueducts along the bridges to the outer circles (..)“

So here we may have direct tribute to the ancient know-how of the Minoans. But we must of course be careful to take these descriptions with a grain of salt, as they may just as easily reflect the ancient works of continental Greece.

Leave a reply