The Arab Occident Water in al-Andalus

The Arabs came not only from North Africa, but also from Arabia, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Egypt. In 711 they conquered Spain, a country that had been occupied by the Visigoths since the fall of the Roman Empire. They brought with them all the Oriental technologies for water management: the ancient shaduf the bucket chain or saqqya, the noria, and qanats. The Arabs preferred developments of more modest scale in the Mesopotamian tradition compared to the grand Roman hydraulic works. The great Roman dam-reservoirs like those of Proserpina and Cornalvo were apparently not brought back into service.

42

It is thought that the oldest Arab project is an overflow dam built at Cordova, the capital of the Umeyyade caliphate. Its total length of425 m exceeds the width of the river Guadalquivir, since it comprises multiple independent segments to increase the effective length of the weir and thus to limit the rise in water level during floods. We have seen this technique earlier in Assyria. The dam is equipped on one side with a large noria which lifts water for the l’Alcazar of Cordova. And at the three angles downstream of its broken line it has water mills, each equipped with four wheels. Many other mills existed along the course of the Guadalquivir, from Cordova down to below Sevilla:

“He who wishes to travel by water from Sevilla to Cordova can embark on the river and travel upstream, passing by the mills of al-Zrada, by the Mannzil Aban bend, [….] the Nasih mills, to arrive in Cordova. [….] At Cordova one sees a bridge that surpasses all others in reputation and solidity. [….] Downstream of the bridge, and across the entire width of the river, there is a dike that is built of stones called “coptes”. The columns are of unpolished marble. On this dike one can see three buildings, each containing four mills.”[341]

But it is agriculture, and its need for irrigation, that is the driving force for the main hydraulic projects. The Arabs establish the cultivation of cotton, sugar cane, and rice in Spain. Agronomy manuals and plants themselves circulate between al-Andalus and the Arab Orient. The Andalusian school of agronomy flourishes, as seen in the treatises of Ibn Wafid and Ibn Bassal at Toledo; Al-Khayr, Ibn Hadjdjadj and Ibn al-Awwan at Sevilla; Ibn Beithar at Malaga.[342] This agricultural development supports significant population growth in al-Andalus between the 9th and 12th centuries.

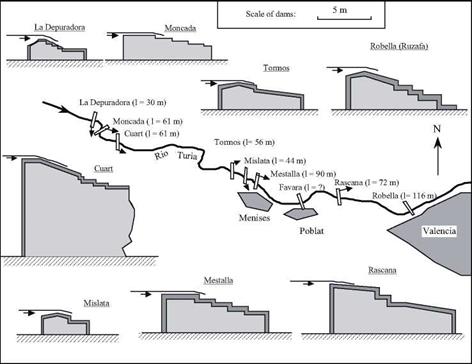

The most celebrated of the irrigation projects is on the river Turia, to the north of Valencia (Figure 7.15).[343] It is possibly the descendant of an ancient irrigation network of the Roman period. Between 911 and 976 the Arabs built masonry outflow weirs covered with large stones sometimes interlocked with iron pins, as we have seen on numerous Arab or Persian dams. Among the nine sills of this system, from 1.4 to 7 m in height, five very likely date from the Arab period – they are mentioned in an edict of the king Jaime II in 1321 after the Reconquest of Valencia. Almost all of these sills have a downstream face in the form of stairsteps to serve as an overflow energy dissipater. Each sill feeds an irrigation canal, alternately on the right and left banks of the Turia river, and all of these canals subsequently branch out downstream.

From 961 any conflicts arising from water distribution, spillage, and the maintenance of the sills and canals are handled by the water tribunal of Valencia. This tribunal, whose deliberations are strictly oral, meets each Thursday in the mosque. After the Reconquest, during which the entire irrigation system is conserved and maintained, this same tribunal meets in the square of the cathedral of Valencia. This tradition continues unchanged to the present day.

Many other projects were developed on virtually all the rivers of the south and east of Spain. Upstream of Murcia there is a rather large dam 7.5 m high and 305 m long on the Segura river[344], built in the reign of al-Hakem (961-976) in a region that had been scarcely cultivated beforehand. It feeds two irrigation canals, one on each bank, with provisions for removal of sediment from the reservoir. These canals branch out extensively, supplying an irrigated domain of 5,000 hectares (and this area triples over the course of the centuries). They extend to downstream of the city of Murcia where another irrigation system, that of Orihuela, takes over. This system makes use of multiple-section sills, as at Valencia, as well as norias. Of course there are also mills, and even boat – mounted mills on the Seguro River near Murcia:

“There are (at Murcia) mills constructed on boats, like the mills of Saragossa, and which, being on the boats, can be transported from one place to another. There one can see gardens, orchards and crops of incalculable number.”[345]

All of these irrigation networks are still in service today, having been repaired and maintained over the centuries.

Mills – both water-driven (horizontal wheels up until the 12th century, then occa-

|

Figure 7.15 The sills of the Turia river, permitting irrigation of the huerta of Valencia from the 10th century. The sections across the structures are shown to the same scale; their lengths are indicated in parentheses. The azudes of Moncada, Mestalla, Favara, Rascana and Ruzafa are surely the oldest; the sills of Cuart and Mislata could be from after the Reconquest of the 13th century. From Fernandez Ordonez (1984). |

sional vertical wheels) and wind-driven (such as at Malaga) – were ubiquitous in Muslim Spain. It is said that there were 5,000 mills in the region of Cordova, and 130 within the walls of Grenada alone. The mills belong to private individuals or groups of individuals, as in the Orient. It is only after the Reconquest that they become privileged feudal and ecclesiastical property, as in the Christian Occident. There was no lack of conflicts for the use of water, given the needs of the flour trade and irrigation[346].

One can find qanats on the grand plateau of Castilla, the most important being those of Madrid. From the very founding of the city by Mohamed Ist (825-886), networks of qanats are put in place to provide water for the city. They are from 7 to 10 km long, with drops of from 80 to 100 m. Indeed, it is perhaps due to the abundance and the quality of water furnished by the qanats that Madrid was chosen as capital of Spain by Philippe II, in 1561.[347] According to the geographer al-Idrissi, a large noria lifts water from the Tagus River up to the city of Toledo.

Leave a reply