The aqueducts of Lyon

Lucius Munatius Plancus founds Lugdunum (Lyons) in 43 BC on the Fourviere hill, 130 m above the waters of the Saone and Rhone rivers. Thirty years later, Augustus makes Lyon the capital of Gaul. It is often the case that such cities are initially established on high ground for strategic reasons, and consequently not well supplied with water. Then the cities rise in importance to become regional capitals, necessitating significant efforts to provide adequate water supply. This was the case of Pergamon as we described in Chapter 5.

At Lugdunum, it was necessary to cross a valley some hundred meters deep to reach the Fourviere hill, only its western facade being accessible. As at Pergamon (but several centuries later), large inverted siphons, the largest in all the Roman world, are used to bring water across the deep valley.

|

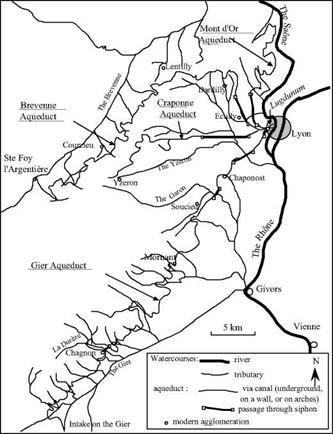

Figure 6.11 The four Roman aqueducts of Lyons. |

|

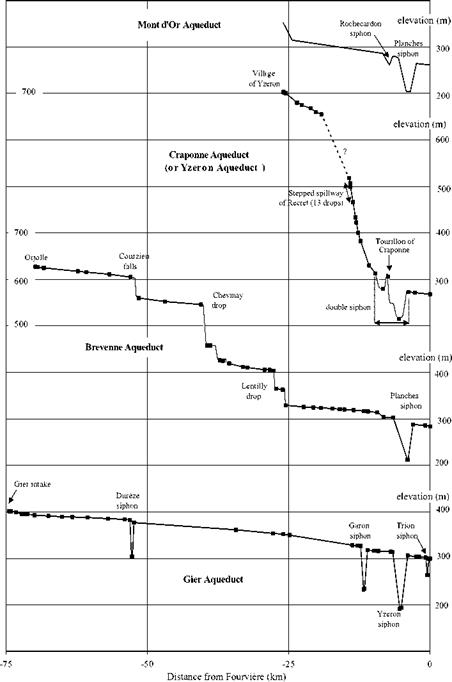

Figure 6.12 Longitudinal profiles of the four Roman aqueducts of Lyon (Burdy, 1979, 1986); the dark squares represent known points.

|

Four large aqueducts supply water to the Roman Lugdunum. They have been the subject of numerous archaeological investigations[235]. Their remains are still visible, but unfortunately are degrading over time; however some additional remains are surfacing during modern construction projects. The construction chronology of these aqueducts is not known with certainty, indeed it is based on hypotheses. One of these hypotheses is that the Mont-d’Or aqueduct, issuing from the mountain of the same name, was the first to be constructed, about 10 BC by Agrippa, the son-in-law and close collaborator of Augustus. (Agrippa was a great aqueduct builder – Rome owes the Julia and the Virgo to him). The Mont-d’Or aqueduct is 28 km long, with two siphons. It is the smallest of the aqueducts in terms of dimensions and discharge, and only a few traces of it remain today.

It is very likely that the Craponne aqueduct (sometimes called the aqueduct of the Yzeron) was built next from catchments developed upstream of the village of Yzeron at 700 m altitude, perhaps under Augustus.[236] This canal is noteworthy for its slope of nearly 17 m per kilometer on the average, i. e. five times steeper than that of the Mont – d’Or aqueduct. Vortex drop shafts constitute what amounts to “hydraulic stairways”. Though the Craponne is of similar length and dimensions to the Mont-d’Or, it is distinc-

|

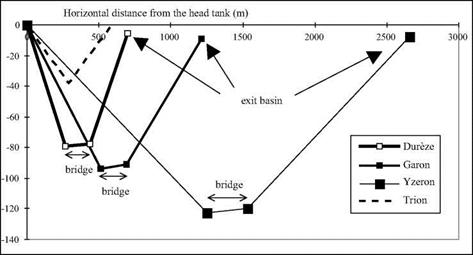

Figure 6.12b. Comparison of profiles along the four siphons of the Gier aqueduct. The Dureze siphon has the most pronounced slope, which can be explained by its later construction (hypothetical) by the Chagnon loop. Note the slightly rising profile (1 % ca.) of the siphon bridges, which allows evacuation of air pockets downstream – discovered by the work of Burdy (1996). |

tive in having a double siphon.

To understand this double siphon, it is useful to reconsider, yet again, the great siphon of the Pergamon aqueduct, whose longitudinal profile shows a high point (Figure 5.10) with a risk of air accumulation. The Craponne includes a free-surface reservoir that stands 15 m above the ground on an intermediate plateau (the Tourillon de Craponne). This reservoir enables the aqueduct to cross two valleys over a total length of 5.5 km, avoiding the problems of a high point. It serves as both an exit basin, or outlet box, for the upstream portion of the siphon and a head tank for the longer downstream portion, which dips through nearly 70 m of elevation.

The Brevenne aqueduct is a very large installation 66 km in length, whose construction could date from the Emperor Claudius in the middle of the 1st century AD. It issues from the Lyon mountains and is buried for the first forty kilometers. Then it follows the valley of the Brevenne and, after some twelve kilometers, has an increased cross section to accommodate intermediate catchments. This aqueduct also has particular distinctive features. It crosses significant elevation changes in short distances at four locations. At Courzieu, it drops nearly 44 m in less than 200 m; then at Chevinay, there is a drop of 87 m in 300 m, and again three other drops of from 30 m to 40 m each. Downstream of the drop of Courzieu, there is a small basin some 45 cm deep and 80 cm long, likely intended to provide energy dissipation as well as to trap transported sand and gravel. Moreover, there is a contraction of the canal at the location of the last drop, at Lentilly; the normal width of 75 cm decreases to 44 cm. It can be shown that in the reaches of steep slope, the flow is supercritical.[237] As for the other aqueducts, the Brevenne terminates at a siphon. It probably merges with the Craponne aqueduct at its entry into Lugdunum.[238]

The fourth aqueduct, Gier, issues from an intake on the river of the same name and is the longest at 74.5 km. The Gier is the aqueduct that was most carefully constructed, and its art features, bridges, and arcades reflect the majesty of the all-powerful Empire at its peak. Ample remains of the Gier are still visible today, in particular its bridges and parts that were supported on arcades. Traditionally the Gier is attributed to the time of Hadrian (beginning of the 2nd century AD), but recent indices (in particular a fountain bearing the name of Claudius) lead us to date the works from the reign of this emperor. The Gier also has two curious features. In parallel with the first siphon, that crosses the Dureze over a length of 900 m, there is a large derivation into a canal of small slope (only 0.5 m/km). This derivation canal goes around the village of Chagnon (the “loop of Chagnon”) for a distance of 11.5 km (making the total length of the aqueduct some 86 km). The purpose of this derivation is not obvious. Along the path of this loop, there is an inscription on a stone noting the rules for riparian use of the aqueducts:

“By order of the Emperor Cesar Trajan Hadrian Augustus, no one has the right to work, harvest, or plant in this space that is intended to provide protection for the aqueduct.”[239]

|

There has been much discussion as to the relative age of the loop and the siphon. If indeed the aqueduct dates from the reign of Claudius, the inscription shows that the derivation canal, in service under Hadrian, postdates the siphon. This may be because the

siphon had maintenance or operational problems caused by the steep slopes in the valley of the Dureze (see Figure 6.12b).

Upstream of the first siphon there is also evidence of an abandoned earlier alignment along 40 km, dug deeply into the rock parallel to the aqueduct, but 8 to 10 m higher. Could this reflect a surveying error?

Further downstream, the Gier aqueduct passes under the village of Mornant in a one – kilometer curved tunnel more than 20 m underground. It has four siphons in all (table 6.4). The third of these siphons crosses the Yzeron valley. 2,660 m long and dropping 122 m, it is the largest siphon of all those in the Lyon complex.

There are eight siphons in all in the four aqueducts of Lyon. Following the specifications in the manual of Vitruvius, each siphon has an exit basin, a head tank, and at the bottom of the valley, a bridge-siphon. The Tourillon de Craponne comprises what

|

Table 6.4 Approximate characteristics of the eight siphons of the Lyon aqueducts (the siphons of the Gier aqueduct are the best known; see Burdy, 1996).

|

Vitruvius might call a colliviaria. Whereas at Pergamon the Hellenistic siphon has a single pipe, here we see the use of veritable batteries of parallel lead pipes. There are no less than nine pipes of average exterior diameter 23 cm (likely 18 cm interior diameter) side by side for the Dureze siphon of the Gier aqueduct, and ten for the Garon siphon (Figure 6.13). There are no remains to indicate the number of parallel conduits for the Yzeron siphon; but taking into account the large size of its reservoir, there were likely 11 or 12 similar pipes (Figure 6.40). The bridge-siphons were particularly wide at around seven meters, to support numerous parallel pipes.

The spring water conveyed by the siphons of Lyon is generally not calcareous, and therefore there is not much encrustation. An exception is the Mont-d’Or aqueduct, which does show evidence of some deposits. The aqueducts arrive into the city of Lugdunum at different elevations. It is thought that the Mont-d’Or aqueduct supplied the thermal baths whose remains have been found in the Minimes area. No traces remain of the water distribution system in the city itself, but it is likely that the conduits passing

under the Saone through siphons supplied the peninsula between the two rivers.

Leave a reply