Romans and dam technology

In about 60 AD the Emperor Nero built his villa at Subiaco, on the river Anio upstream of Tivoli (Figure 6.8). He formed lakes for his personal pleasure by damming the river. The largest of the structures he built for this purpose is across a natural gorge and at 40 m, is the highest dam of all the Roman Empire. Rectilinear, 80 m long at its crest and 13.5m thick, it is what one would call today a gravity dam, relying on friction at its base to resist the force of water in the reservoir behind it. This dam remained standing until 1304, when the monks of a neighboring monastery dismantled it to recover the stones for other use.[263] Forty years after Nero, Frontinus built the new intake for the Anio Novus aqueduct on one of these lakes to improve the quality of its water, as we have seen earlier.

Nero’s dam at Subiaco is not only the highest, but also one of the first dams constructed by the Romans, and the only one in Italy. Since dams were not essential to the development of Italy, dam technology is not a traditional Roman discipline (Vitruvius says nothing of dams in his treatise On Architecture). We have seen in the first part of this book that numerous dams were built in the Orient from the IVth millennium BC. It is undoubtedly through their domination of the Orient (Syria-Palestine, Egypt) and through their military expeditions (Yemen) that the Romans acquired this technology and then further developed it, especially from the 1st century AD.

Like those of the Orient, Roman dams are almost always of the gravity type, the one at Subiaco being a good example. These dams most often are built of simple rectilinear walls of masonry or concrete, supported by earth fill or buttresses, as we will see further on. However the Romans also invented the arch dam, a structure whose shape enables it to transmit the pressure force of impounded water to the lateral valley walls, just as the arch of a bridge transfers the load to its supporting piers.

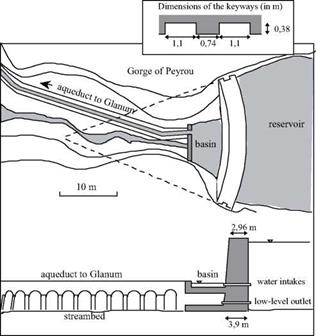

In the valley of the Baume, several kilometers south of Saint-Remy-de-Provence in France, are the remains of a structure that is now buried under a dam built in 1891. A provincial scholar named Esprit Calvet fortunately discovered these remains in 1765 before they were buried. The principal vestiges of the dam are the keyways in the valley walls where the dam abutments were anchored. The shape and alignment of the key – ways, which extend somewhat above the level of the modern dam, reflect and reveal the curvature of the structure (Figure 6.26).

A recent study led to reconstitution of the dimensions and function of this Roman dam.[264] It is likely during the time of Augustus that the Romans built the dam in the narrow gorge of the Peyrou to supply an aqueduct leading to the nearby Roman city of Glanum. This structure, the first known arch dam, is nearly 15 m high, 23.8 m wide at its crest, and has a radius of curvature of about 30 m. The dam is keyed into the nearly vertical rock walls of the valley at its two ends. It apparently is built of either two faces of quarried rock blocks with an impermeable fill, or perhaps a solid mass of mortared blocks with a watertight joint.

Figure 6.25 The dam in the Baume valley, near Sant-Remy-de – Provence: the oldest known arch dam (from the reconstitution of Agusta-Boularot and Paillet, 1997). The water transported by the aqueduct is destined to supply a massive fountain at Glanum, perhaps a watering station for migrating herds. The aqueduct is 500 m long, with a slope of 3.2 m/km. The canal is 0.59 m wide, and 0.89 m deep.

Figure 6.25 The dam in the Baume valley, near Sant-Remy-de – Provence: the oldest known arch dam (from the reconstitution of Agusta-Boularot and Paillet, 1997). The water transported by the aqueduct is destined to supply a massive fountain at Glanum, perhaps a watering station for migrating herds. The aqueduct is 500 m long, with a slope of 3.2 m/km. The canal is 0.59 m wide, and 0.89 m deep.

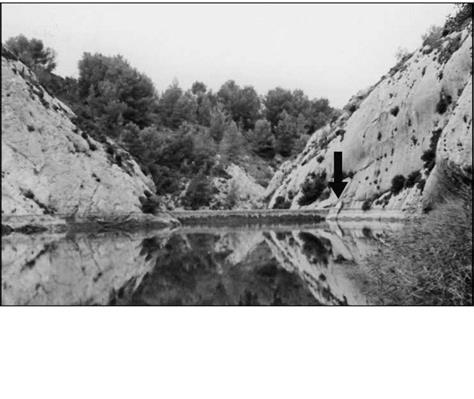

Figure 6.26 In the Baume valley, site of the Gorge of Peyrou, seen from the reservoir. The arrow shows the location of the keyway of the Roman dam, at the right extremity of the present-day dam (photo by the author).

Figure 6.26 In the Baume valley, site of the Gorge of Peyrou, seen from the reservoir. The arrow shows the location of the keyway of the Roman dam, at the right extremity of the present-day dam (photo by the author).

To the south of Evora in Portugal there is another small arch dam: Monte Novo. It is less than 6 m high, but is probably of Roman heritage.60 The only other known example of an arch dam revealing Roman techniques is the one built at Dara (Anatolia) in the Byzantine period (Chapter 7).

The dams built for Nero on the Anio were expressly for the personal pleasure of an emperor. On the other hand, the dams that we describe now respond to economic needs; the provinces had to produce enough food to supply the Empire. In Spain, in North Africa, and as always in the Orient, irrigation was essential to the development of agriculture.

Leave a reply