Paddle wheels and water mills in the Roman world, the beginnings of industrial use of water

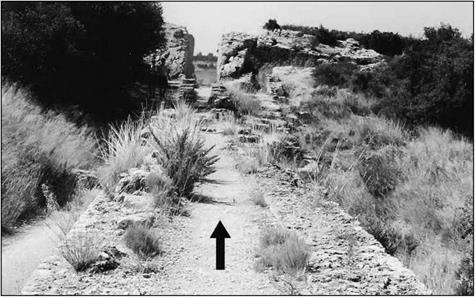

In the provincial countryside some ten kilometers from Arles in the direction of Saint-Remy-de-Provence, a hiker can come upon the remains of Roman aqueducts on arches. These remains are even indicated by a sign. Looking at the remains closely, the tourist can easily see that there are in fact two parallel aqueducts, side by side. If the hiker follows the path alongside these aqueducts, he or she comes upon a deep notch cut in a rocky outcrop. The canal of the left aqueduct passes through this notch (Figure 6.19).

After passing through this notch, our hiker then comes out at the top of an escarpment, 20 meters high along a length of 60 meters, beyond and below which is a broad plain with no visible trace of the aqueduct. On the slope one can recognize the ruins of walls and structures in the form of stairways (Figure 6.22). These ruins were identified in 1935 by Fernand Benoit as those of a Roman hydraulic flour mill, the mill of Barbegal, the very first of this kind known to us.

|

Figure 6.19 Barbegal: the remains of the canal of the left-hand aqueduct, and the notch in the rocky outcrop that marks its end (the right-hand aqueduct, though it cannot be seen in this photo, turns sharply before the rocky outcrop and continues its route toward Arles) (photo by the author). |

In Chapter 5 we mentioned the appearance of the water mill in Asia. This was only weakly suggested by an allusion of Strabo to the mill in the palace of Mithridate, king of Pontus, conquered by the Romans in the middle of the 1st century BC. The appearance of this device marked a major step in the history of technology, but passed almost unnoticed. With the Romans, the first written evidence of a mill is found in book X of Vitruvius’ work. Let us examine how Vitruvius describes the new technology to get a clearer idea of how it appeared.

Leave a reply