Other Roman ports and navigation works

We should not forget the role of the port of Alexandria during the Roman period, as it closely follows the Ostia complex in importance. The port was built in the Hellenistic period, and we have already described it at the beginning of Chapter 5 (Figure 5.2). A squadron of Roman warships is based at the port, a point of departure for Egyptian wheat bound for Rome (via Pouzzuoli before completion of the port of Trajan). But Alexandria is also an intermediate stop for products coming from Sudan, Arabia, and the extreme Orient. The Romans continue to use and maintain the canal of Necho that we described in Chapter 3. Trajan develops Clysma (Suez) and undertakes repair of the canal.[292] The canal constitutes one of the routes to Arabia, India, and China, without ever really seriously challenging the grand ports of the Red Sea (Myos Hormos, on the site called Qoseir on Figure 3.1, and Berenice, formerly Head ofNekheb).

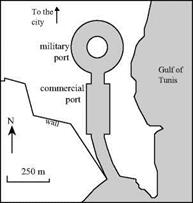

The port of Carthage, the most important of Africa, is also a point of departure for wheat bound for Rome. We have mentioned the wealth of the Roman Cartago earlier, from its refounding by Augustus in 29 BC up until the 7th century AD when it is destined to be eclipsed by the modern Tunis. The port has two basins (Figure 6.37), one for military uses and the other for commercial traffic.

|

|

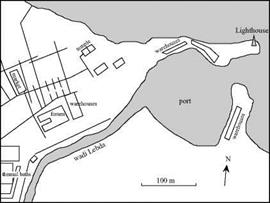

It would be difficult to mention all the other Roman Mediterranean ports. Some are excavated into level ground or in natural creeks, like Carthage and Marseille; others are developed in the mouth of watercourses, as is partially the case of the complex of Ostia, often with the same accompanying problems of sediment management. The port of Leptis Magna, the native city of Septimus Severus, is situated in the mouth of the wadi Labda. This emperor develops the port (Figure 6.38) and erects a lighthouse there. As a typical Mediterranean watercourse, the wadi Labda is subject to rapid and violent floods, and these can endanger vessels or cause other significant damage. As we have

Figure 6.37 The port of Carthage Figure 6.38 The port zone of Leptis Magna (after

(after Scarre, 1995). Scarre, 1995).

seen for some other African dams, a flood diversion structure is built upstream on the wadi Labda. A similar scheme is used by the Romans for Seleucid, the port of Antioch (with a 130-m long tunnel, followed by a 700-m long open cut, 6 to 7 m wide).

The Romans are not great canal builders – even though they maintain and use the Necho canal, or canal of two seas, and rename it the canal of Trajan after this emperor’s work on it. There is some fainthearted thought given to the construction of a canal at Corinth, cutting across the isthmus to enable ships to avoid having to sail to the south of Peloponnese. Caesar, Caligula, and Nero are tempted by this project, and initial work is begun.[293] But there is concern that the sea level may be different from one end of the canal to the other,[294] and that the opening of the canal would provoke a catastrophe. Or perhaps it was simply that the economic stakes were not high enough, for Greece is, under the Empire, more of a symbol than a significant economic player. In any case, the canal was not built in Antiquity.

Leave a reply