Other aqueducts in the Roman Empire

The panorama of Gallo-Roman aqueducts that we have just described represents the diversity of situations and solutions adopted throughout the Roman Empire. Table 6.1 gives an incomplete list of the numerous Roman aqueducts that have been discovered and studied. It would be impossible to describe all of them. To the best of our knowledge, the longest one is at Apamea-on-Orontes in Syria, built in 116 or 117 AD as part of the broad reconstruction after the earthquake of 115 AD.[246] But another aqueduct also merits our attention. It is the aqueduct of Carthage, one of the marvels of Roman architecture in Africa, and among the longest of all the Roman aqueducts in the western world (Figure 6.18).[247]

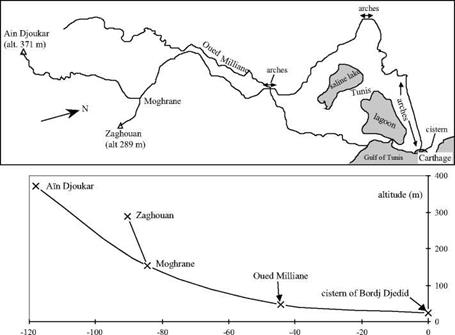

Carthage is destroyed by the Romans at the end of the Punic wars, then rebuilt in 29 BC by Augustus for the purpose of granting property to legionnaires at the end of their service, and then later becomes a capital of the province of Africa. With completion of the great thermal baths of Antonio, it becomes necessary in 162 AD to build an aqueduct to supply numerous public fountains, and also to build cisterns to store rainwater. But the usable water sources are some distance away, in Djebel Zaghouan. The closest source is 56 km away as the crow flies, with obstacles in the way including a lagoon to the east of Tunis, and a saline lake somewhat further. At the wide valley of the wadi Milliane there is a crossing of 4.5 km on arches that are some 20 m high in places, and a two-level bridge 126 m long and 34 m high.[248] In this plain of Carthage there are 17 km of crossings on high arches in all. Later on, very likely under the Severus emperors, the aqueduct is lengthened to 132 km, to capture the even more distant springs of Ain Djoukar.

|

Distance from the cistern at Carthage (km) Figure 6.18 The aqueduct of Carthage: map of the alignment and schematic longitudinal profile (after Rakob, 1979). Only the points indicated (x) are exact, the remainder of the profile is deduced from simple interpolation. The maximum capacity is estimated at 25,000 m3/day. |

Like the Pont du Gard in Europe, the aqueduct of Carthage and its appurtenances attract the admiration of African observers:

“This distance, from the source (Ain Djoukar) to the cisterns (the 24 cisterns of Carthage) was covered thanks to an infinite number of aqueducts, in which water flowed at a constant level. These aqueducts were composed of stone arches. When these were on the ground, they were low and when they were in the depressions or valleys, they were extremely high. This was one of the most remarkable things to be seen on the surface of the earth.” [249]

The upstream portion of the aqueduct is still used today by the Tunisian water service.

Leave a reply