On the river to Nubia, navigation works on the Nile (IIIrd and IInd millennia BC)

Navigation canal at the first cataract

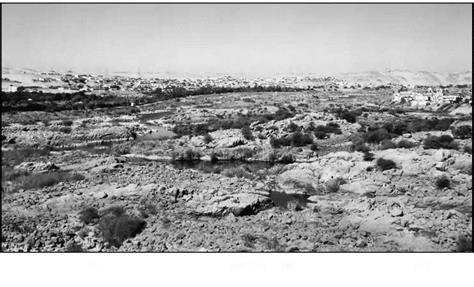

Nubia is rich in quarries, and in gold and amethyst mines. A concerted effort to exploit these resources of the south began in the VIIth Dynasty, under the ancient Empire. But the Aswan rapids, comprising the first cataract of the Nile (Figure 3.4), present an obstacle to navigation. In about 2400 BC the Pharaoh Merenre I has his close lieutenant Ouni build a flume system to allow boat passage through this obstacle. Ouni, who later becomes governor of Upper Egypt, had his autobiography engraved in his tomb, where one can read the following:

“Then His Majesty sent me to dig five canals (flumes?) in Upper Egypt and to construct three

barges and four transport boats, from acacia wood of the land of Ouaouat. The chiefs of the

lands of Ouaouat, Iam and Medla had the wood cut for this. I accomplished all of my task in

a single year. When the boats were launched, they were also loaded with big wide blocks of

1 3

granite for the pyramid (of Merenre)"

This account tells us the main reason for Ouni’s mission: the descent of boats com – [98]

ing from the stone quarries. The current in the flumes was surely too strong for upstream passage. The flumes were rebuilt, or enlarged, under the reign of the Pharaoh Sesostris III (XIIth Dynasty) in about 1870 BC, height of the middle Empire. But now the reasons were clearly military, since the work enabled Egyptian expeditions to travel upstream to the second cataract (in years 8, 12, 16 and 19 of the reign).[99] But clearly these flumes either were undersized or filled with sand, which would be no surprise given the strength of the currents in this area and therefore the sand load carried by the flow. New work was conducted under Thoutmosis I and Thoutmosis III, between 1490 and 1425 BC, this time including the construction of a true canal 10 m wide and 7 m deep.[100]

Herodotus did not travel upstream of the first cataract during his voyage in Egypt. Here is how the navigation conditions in this zone were described to him:

Herodotus did not travel upstream of the first cataract during his voyage in Egypt. Here is how the navigation conditions in this zone were described to him:

“From the city of Elephantine, going upcountry, the land is steep. There travelers must bind the boat on both sides, as one harnesses an ox, and so go on their way. If the rope were to break, the boat would be borne to its destruction by the strength of the current. This part of the country is four days’ journey by boat, and the Nile here is as twisting as the Maeander; there is a length of twelve schoeni to pass through in this fashion.”[101]

Strabo’s much later account of his trip up the Nile (by land route) beyond the cataract does not mention these works, indicating that the canal was no longer in service. It is not hard to imagine that it was quite difficult to permanently maintain such a project, without locks, in an area of strong currents.

Figure 3.4 Rough terrain at the site of the first cataract, upstream of Aswan, at low water (photo by the author)

Leave a reply