Machinery: hydraulic mills and wheels, lifting machines and norias Lifting machines

Water lifting machines respond to a very basic need of civilization – that of raising water from a river, canal, or cistern for its distribution to agricultural or urban uses. The Near East had used the shaduf (Figure 2.4), a balance-beam device, for a very long time – but this device was not used in China. We have seen that more sophisticated devices appeared in Egypt during the period of Alexandria (the end of the 3rd century BC), then in the Roman Empire. Examples include the Ctesibios pump (Figure 5.5), the Archimedes screw (Figure 5.3) and the muscle-powered lifting machine (Figure 6.20).

The first written evidence of lifting machines in China is found in a treatise of Wang Ching during the latter Han period (80 AD). We cited this treatise earlier in summarizing the innovations of the Han period, and here is a specific extract:

“In the streets of the city of Loyang there was no water. It was therefore pulled up from the

River Lo by water-men. If it streamed forth quickly (from the cisterns) day and night, that was 82

their doing”.

Another text from 189 AD is more explicit, again concerning the question of water supply in the capital Luoyang:

“He (the minister Chang Jang) further asked Pi Lan to cast bronze statues… and bronze bells… and also to make (to cast) “Heavenly Pay-off” and “Spread-eagled Toad” (machines) (which would) spout forth water. These were set up to the east of the bridge outside the Phing Men (Peace Gate) where they revolved (continually, sending) water up to the palaces. He also (asked him to) construct square-pallet chain-pumps and “siphons”, which were set up to the west of the bridge (outside the same gate) to spray water along the north-south roads of the

city, thus saving the expense incurred by the common people (in sprinkling water on these

83

roads, or carrying water to the people living along them).”

This text refers to the simultaneous use of several different machines. According to Joseph Needham and his collaborators, the siphons mentioned here are probably simple piston pumps, like those used in China to pump brine from the salt mines. Perhaps other machines in use were manual lifting wheels.

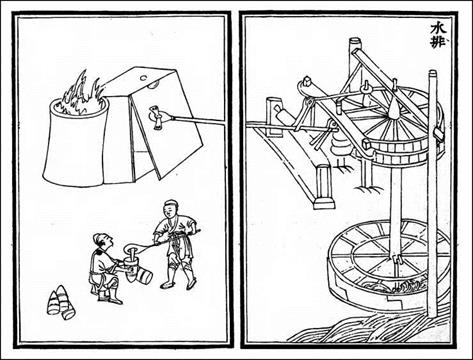

The pump with chain and square paddles (rectangular, in fact), also called the dragon backbone machine, is explicitly mentioned in the text. It is typical of Chinese inventions, and Figure 8.18 gives an idea of its workings. It is a wooden chain fitted with rectangular paddles, circulating in a long wooden flume that is open at each end, inclined at 25° or less from the horizontal. Water is lifted by the upwards movement of the paddles inside the flume. The chain to which the paddles are fixed was originally powered by men (or young girls) on a pedalboard. But from the 12th century one encounters descriptions of these machines as powered by animals, and even by hydraulic wheels. The lifting height can be of the order of 5 meters.

Rice cultivation developed rapidly under the Tang and the Song, and this agriculture requires intensive irrigation. The authorities favored the dragon backbone machine to lift water into the rice fields. In 828 they even standardized the specifications for this pump, whose great success can be attributed to its ergonomics. In the 12th century its use in Turkestan is noted on the occasion of a voyage of a Taoist wise man, then it appears in Korea in the 15th century. Between the 17th and 19th centuries it is used to various extents throughout the world.[446] [447]

A parallel technology to the dragon backbone machine is the noria. This hydraulic – powered lifting machine is already well known to us – in Chapter 6 we cited the description given by the Roman Vitruvius in about 25 BC, and we have seen its very broad use in Syria and in the Arab world. But the history of its introduction in China is an enigma. There is clear evidence of the use of hydraulic energy in China ever since the beginning of the Christian era, but the Chinese hydraulic wheels appear to be mostly horizontal, with vertical axes. The noria appears in Japan about 800, but one cannot find serious evidence of its use in China before the 10th century, and indeed there is no indisputable evidence prior to 1130. When one encounters the noria in Korea in the 15th century, it appears as an alternative lifting technology to the square-pallet chain pump, and it comes from Japan, not China.[448] These observations suggest that there may have been

|

two pathways for the introduction of the noria in Asia: by land in the region of the upper course of the Yellow River in China on the Silk Road around the 10th century; and in Japan by sea from India two centuries earlier.

In his account of his Voyage in China (1345), Ibn BattUta describes wheels on the Yellow River that appear to be norias:

“(The Yellow River) is lined with villages, cultivated fields, orchards, markets, in the manner of the river Nile in Egypt; but here the land is more flourishing, and on the river there are a large number of hydraulic wheels.”[449]

The Chinese noria is very light, made of wood and bamboo, and therefore it can be turned by a weak current. The most famous of these wheels are those in the region of Lanzhou on the upper course of the Yellow River. Some fifteen meters tall, they are arranged in batteries or sets of up to ten per row.[450]

|

Figure 8.19 Forge bellows powered by hydraulic force; illustration of 1313 (from Needham and Ling, 1965). |

We have seen that the bucket chain or saqqya was widely used in the Arab world. But it was used only marginally in China, and then probably only in the salt mines of Sechouan at a relatively late date.[451]

Leave a reply