Irrigation works in North Africa

Lucius Septimus Severus was born at Leptis Magna, capital of Cyrenaica (today’s Libya), at the end of the 2nd century AD. After the death of the Emperor Commodius in 192 AD, Severus emerges victorious from the civil wars, and becomes emperor in his turn, founding the dynasty of the Severians. North Africa had already been a prosperous region for some time; we have mentioned earlier the great aqueducts of Carthage and Cherchell (Lol Caesarea), testaments to the prosperity of these cities. But the new emperor adorns North Africa even further, battling the desert nomads, building roads and fortifications, and creating the new province of Numedia to the west of present-day

Tunisia. Severus had a natural attachment to his native country, but was also motivated by the desire to support new colonists and to create new lands for production of cereals to help feed the Empire.

The Romans built some 130 dams for irrigation in North Africa, counting only those structures with known remains.[270] The dams were likely constructed in the 2nd century

|

|

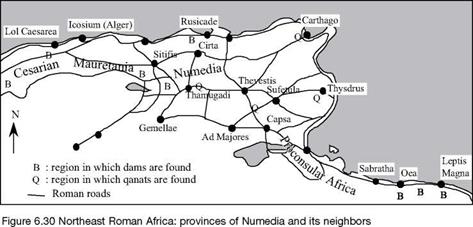

AD (i. e. somewhat later than the dams in Spain). Some of the dams were intended to trap alluvial sediments and thus help create arable land, following the ancient technique of the Nabatians. One of these dams, near Leptis Magna, was built to divert flood waters of the wadi Labda, a watercourse at whose mouth the city’s port was developed (Figure 6.38). As far as we know, the highest of the dams was some ten meters; the longest is about 260 m. These are gravity earth dams, sometimes with buttresses, that can be submerged by violent floods of the wadis without suffering damage. Some 70 dams are thought to have been identified in the region of Leptis Magna and Tripoli (Oea); thirty in the region of Constantine (Cirta), Setif (Sitifis) and Rusicade; and fifteen around Cherchell (Lol Caesarea). The largest dam is that of Kasserine in Tunisia, on the wadi Derb, in a grain region not far from Sbeitla (Sufetula). This dam includes a wall 7 meters thick at its base and 4.9 m at its crest, 10 m high, and about 130m long. It has since been replaced by a modern dam on the same site.

There are also qanats in the Roman provinces of proconsular Africa and Numedia.[271] In North Africa, they are later called kettaras, or foggaras. We have seen in Chapter 2 how this technique was spread into numerous sectors of the Acheminides Empire by the Persians. We encountered it again in the oases of Egypt (Chapter 3). As we will see further on, it is obvious that the Romans maintained and developed qanats in the Orient. It is therefore no surprise that qanats are found in the eastern part of the African provinces: at El-Djem (Thysdrus), between Tebessa (Thevestis) and Gafsa (Capsa), near Carthage and, more to the west, in the region of Timgad (Thamugadi). The latter are attributed to the period of Commodius, i. e. the end of the 2nd century AD. Latin inscriptions sometimes attest to the Roman origin of the qanats, as in the region between Tebessa and Gafsa, or as at Timgad:

“Facility for the collection and delivery of underground water.”[272]

The Roman origin of the qanats is assumed in many other situations. The above observations make it tempting to accept the hypothesis of Henri Goblot, according to whom it was indeed the Romans who imported the qanat into Africa. Much later, the Arabs diffuse the technique even further, toward Spain and Morocco.

Leave a reply