Innovations under the Han

The first imperial era was of great importance to the blossoming of China thanks to its cultural unity and construction of hydraulic infrastructure. Before moving on, we need to note the appearance of several other important innovations.

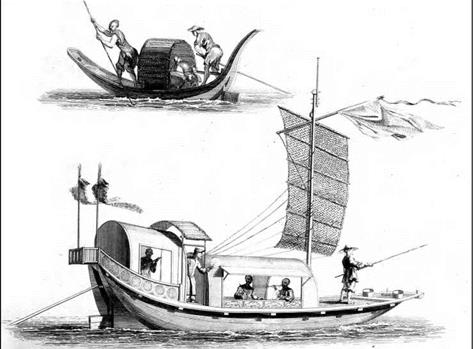

One innovation is the axial ship rudder (see Figure 8.10). We know that it appeared during this period from a terra-cotta scale model of a junk that dates from the 1st century AD and was discovered in a tomb at Canton.[421] At first, this was a movable rudder mounted on the stern of the hull. Later, it is attached to the sternpost of junks. The axial rudder is not adopted in the West until the 11th century.

A second innovation is the water wheel, appearing during the time of Wang Mang at the beginning of the 1st century AD. It is curious that the first literary references to the use of hydraulic energy in China are not about water mills, but about much more complex industrial applications. The first mention of a water wheel appears in 21 AD. This wheel is probably horizontal, and its axle shaft is fitted with cam lobes to drive an assembly of pestles.[422] The system is used to crush grain, and also to power forges. Ten years later (31 AD) a certain Du Shi, the son of Zhao Xincheng who built the dam that we described earlier, introduces the use of hydraulic energy to power piston bellows in the forges at the important metallurgical center Nanyang.[423]

While the axial rudder is clearly a Chinese invention, the hydraulic wheel is more likely an imported technique since there is evidence of its use somewhat earlier in Asia Minor at the beginning of the 1st century BC (see Chapter 5). The spread of this technology into China is more or less contemporary with its appearance across the Roman Empire, albeit for different applications. However the exact origin of this invention remains obscure.

Another innovation that appeared under the “latter” Han appears rudimentary but is extremely effective for raising water. It is a device comprising a wooden chain fitted with rectangular paddles, like quoits, and powered by a sort of chain wheel (Figure 8.18). This square-pallet chain pump, the dragon backbone machine, is destined to spread throughout the lands of Chinese culture, and we return to this later on. It likely grew from the need for cities to lift water from cisterns or watercourses. We know from a treatise of Wang Ching in about 80 AD that in the capital Luoyang, men are employed “night and day” to lift water from cisterns to the street level – but he does not describe how it is lifted. A century later, in 186 AD, another treatise mentions the paddle pump very explicitly, again in the context of lifting water to the street level at Luoyang.

These lifting machines probably supplied water distribution networks of some sort. Conduits of stone or terra-cotta have been found dating from the Qin or Han periods.[424]

Bamboo tubes were probably used as well.

Another innovation that appeared in China in the 2nd century AD is the modern sail,[425] that is, a sail carried by a boom or yard that pivots around the mast. This type of sail rig can point into the wind, and it is not necessary to lower the sail when coming about, since the sail pivots on its own when the boat turns across the wind, or tacks. The Chinese sails were made of braided bamboo, stiffened with battens or yards so that they

|

Figure 8.10 The rudder on Chinese boats (engraving of Chambers, 1757 – ancient archives of ENPC). |

do not luff when brought close to the wind. It is not necessary to lower the sails when the boat is moored, and when the wind freshens, it is easy to reduce the sail area.

At the same time as the galley ship is being developed in the West, these Chinese sailing innovations support considerable coastal navigation along the shores and rivers of China, in particular on the Yangtze.

Under the Han, some canals are provided with gated openings. The Bian canal is the principle example; we saw earlier that such gates are mentioned as part of the reconstruction works of 70 AD. They are also mentioned in an older account, again from Jia Ran in 6 BC whose report proposes solutions to prevent flooding from the Yellow River: “We could construct a rock dike from Chhi-Khou toward the east and build many gates. [….]

I fear that this proposal will attract criticism saying that the river is too large to be controlled. However, we can evaluate our chances of success from the experience that we have on the Bian canal at Jung-Yang. At this location, the openings or gates were only made of wood, and set directly on the earth of the dike. Therefore, if we constructed these dikes out of rock, with good foundations, the safety of the works would be assured. [….] During the dry season, the lowest gates to the east should be opened to irrigate the countryside of Chichow, and during the flood season, the large gates of the west should be opened to route the river’s floodwaters far away.”[426]

|

The existence of gates on small irrigation canals stems from olden times that cannot be precisely pinned down. It is unlikely that they are in general use on large canals

throughout China until the 1st century BC, for Sima Qian does not mention anything like them in his observations. Recall that such gates existed in Egypt during the Ptolemite period, 3rd century BC, at the end of Necho’s channel – as well as in the Fayoum depression (Chapter 5). The principle of a portable plank-dam was well known even earlier in Syria (see Chapter 2, the dams around Ugarit). In China, these single gates generally consist of several planks laid horizontally, one on top of the other, between guides set into each bank. On the larger applications, the planks are interlocked, and the assembly is operated using a system of pulleys and counterweights.[427]

On the navigable canals the gates are closed to maintain sufficient water depth when the discharge is low with respect to the slope of the canal. When the gates are opened,

boats moving downstream are carried by the wave that is created. Boats moving upstream, on the other hand, must be winched upstream of the gates using a capstan. After the gate is closed it takes some time before the water depth increases sufficiently for navigation to resume. This clever system constitutes the principle of the Chinese flush lock. As we see further on, this type of simple lock sees broad use on the Grand Canal.

Finally, even though this does not directly involve hydraulics, we must also note another Chinese innovation of this period: the humble but ergonomic wheelbarrow.

Leave a reply