In the heart of the Arab world: the splendor of the Umeyyades and the Abbassids

Byzantium, the Sassanides and the new Arab empire

Water supply systems of the Byzantine cities do not measure up to those of the Romans, either in quality or in quantity. In many Byzantine cities, such as Apamea-on-Orontes or even Constantinople itself, aqueducts are abandoned in favor of cisterns, sometimes very large and fed by runoff from rainstorms. Small rural communities located along wadis or on small rivers implement numerous hydraulic developments at their scale[317] –

such as modest derivation canals that support gravity irrigation of valley fields, with many small mills.

The Byzantines indulge in large-scale hydraulic activity in Anatolia, where they build several dams. One among them is the Dara dam, constructed under Justinian (527565) on a tributary of the Khabur. It probably has an arch in its central portion – at least this is what Procopius of Caesarea, in the 6th century, attributes to the dam’s architect, Chryses of Alexandria:

|

|

“He did not build the dam in a straight line, but in the form of a crescent, such that this arch, turned against the stream of the water, could better resist its violence.”[318]

At about this time, and at the other end of the Syro-Mesopotamian universe, a great misfortune occurred in what had been the land of Sumer: the submergence of the irrigated lands of lower Mesopotamia, with new marshes that rendered the land useless during all of the Middle Ages. The bed of the Persian Gulf had been filling with sediment since the Bronze Age (Figure 2.1). The fields created by alluvial deposits of the great rivers are relatively low in elevation, and only drained thanks to the inhabitants’ continuous

efforts.[319] [320] [321] Repeated ruptures of the dikes along the Tigris occur during the time of the Sassanide sovereign Kawadh (488 – 531). His successor Khusraw I (531-579) manages to repair the dikes. But on the eve of the Arab conquest, one hundred fifty years later in 627 or 628, there is a catastrophic flood of the great rivers. Khusraw II is powerless to manage these floods, despite an interesting means of managing human resources. This is told to us by al-Baladhori, one of the most ancient Arab historians (he dies in 892): “Then when arrived the year when the Prophet (God bless him and give him peace!) sent as ambassador to Chrosroes-Parviz (Khusraw II, 590-628) Abdullah son of Hodhafa as-Sahmi, that is to say in the year 7 or 6 of Hegire the Euphrates and the Tigris had a considerable flood, such as had never been seen before or after: large breaches opened that Parviz tried to close, but the water was stronger and reached the low country, submerging villages and crops and several land districts in this place. Chrosroes came to the site in person to block the breaches: he laid a pile of silver on a leather tablecloth and put to death those workers who did not work hard enough (it is said that on a single dike he put under the cross, in one day, forty of those who worked there), but he could not stop the water. At the same time, the Arabs invaded Iraq and the Persians became henceforth preoccupied by war, to the point that the breaches grew larger without anyone worrying about it: the landowners in the villages were power-

22

less to block them, so large were they, so the marshes grew in extent.”^

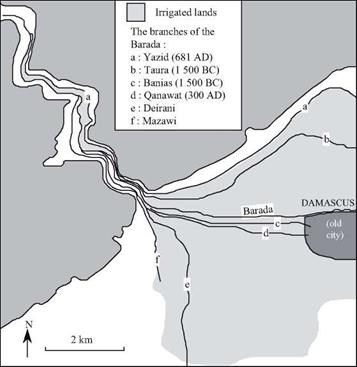

The Umeyyades installed the capital of their empire at Damascus not long after the Arab conquest of Syria, (661 to 750 AD). This empire soon extended from the Atlantic ocean to the Indus. Damascus, a city that had prospered since the Bronze Age thanks to the water taken from Barada where it comes out of the Anti-Lebanon mountains (Figure 7.6), quickly becomes the very image of paradise, with its gardens and orchards. Yazid, the second Umeyyade caliph, builds a new canal coming from the Barada (after which the canal is named) and establishes a pattern for the cultivated zone, the Ghouta, that will last for all of the Middle Ages. The Andalusian pilgrim Ibn Jubayr, in the 12th century, tells us of the charms of this region:

“The gardens surround Damascus as a halo surrounds the moon (….). To the east, the green Ghouta extends as far as the eye can see and no matter which direction one looks, its sparkling splendor transfixes the gaze. How true is what one says of Damascus: If paradise is on the earth, Damascus is it, and if paradise is in heaven, Damascus is its rival and just as wonderful!”^

The Umeyyades use Egypt as a granary, much as did the Romans and then the Byzantines, and send wheat to Arabia using the ancient canal of Necho between the Nile and the Red Sea (Figure 3.8). They renovate the canal about 641 and rename it canal of the Caliphs.

To foster the economic development of Syria and Iraq, the Umeyyades continue the

|

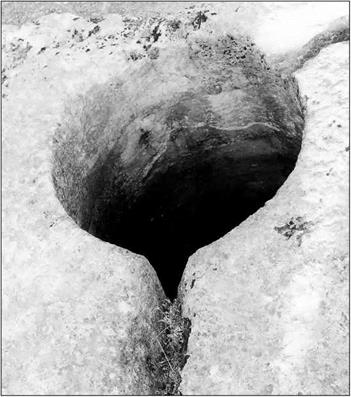

Figure 7.6 The arms of the Barada artificially branched off to irrigate the Ghouta of Damascas (after Kamel, 1990). In 1185, ibn Jubayr observes these seven arms from the top of a hill he climbed as a pilgrim: “This blessed hill (according to the Koran, Jesus and his mother took refuge on it) marks the beginning of the city gardens and the line of separation of the watercourses that divide into seven branches each going in a different direction. The most important of these is the Taura that passes below the hill and that is dug into the rock as an underground canal, as large as a grotto. Now and then an audacious swimmer, a young boy or a man, dives from the heights of the hill into the river and swims underwater to cross the canal below the hill and comes out downstream. But this is a very risky undertaking! From the hill, one can look over all the gardens to the west of the city. No vista rivals this one in beauty, splendor and perspective.”24 |

ancient Roman method of conceding undeveloped land to colonists – friends of the powerful, retired soldiers, even entire tribes. Then, when the lands begin to produce a harvest, the colonists pay a tax to the central treasury. Under the first caliph Mu’awiya (661 – 680), and under his successors al-Walid (705 – 715) and Hisham (724 – 743), the marshland reclamation works in lower Mesopotamia are financed by the close colleagues of the caliph, who later take possession of those lands:

“The breaches having opened during the time of al-Hajjaj (the governor of Iraq), he wrote to al-Walid (the caliph) to inform him that the cost of closing them would not be less than three million dirhems. Al-Walid judged this to be excessive, but his brother Maslama offered to [322] undertake it himself, under the condition that he would be given rights to all the lands that would remain submerged, once the three million dirhems had been spent. [….] Al-Walid accepted: Maslama thus obtained several adjoining land districts. Then he had two canals dug from as-Sib, brought in peasants and farmers, and brought these lands under cultivation: these people prospered and formed numerous villages, to take advantage of the protection they would offer.”[323]

In 750, the Abassids come to power and massacre all the Umeyyade family save one, who flees to found the caliphate of Cordoue. The definitive closure of the canal of Necho, associated with the troubles in Hedjaz, occurred at the beginning of this new dynasty in 767. The closure is ordered by the caliph al-Mansour, to prevent the shipping of wheat toward the revolting cities of Mecca and Medina and to prevent an invasion that might make use of the canal. The Abbasids relocate the capital to the city of Baghdad, founded in 762 on the Tigris. From 836 to 892 the capital will be moved once again a bit further upstream, to Samarra. From the 11th century this will be the era of the Seljuk Turks, with a general distribution of power. Before long it becomes a defacto split. One side of the split is the Syrian-Egyptian world of the Fatimides, the Ayyubids (the Saladin Dynasty, enemy of the crusaders) and the Mamlukes. The other side is the Persian and Iraqi worlds that are more oriented to Central Asia under the influence of Persian and Mongol leaders.

Leave a reply