Hydraulics in the Roman empire: Driving Force of development and symbol of civilization

The Etruscan hydraulic heritage and the beginnings of Rome

Civilization does not truly begin to develop in the western Mediterranean until the beginning of the 8th century BC. This begins according to the legend when the Phoenicians, led by Elissa, princess of Tyr, found Carthage on the Tunisian coast. Then the Greeks establish colonies in Sicily and in the south of the Italian peninsula in the middle of the 8th century BC. These colonies become a cultural ensemble called Greater Greece. But the capital event for Italy during this same period is the arrival of yet another people who settle to the north of the Tiber. According to Herodotus, these new arrivals came from Anatolia. In response to an extended period of famine, the king of the Lydians has his son Tyrrhenios lead half of his people out of their homeland. They take to the sea, traveling westward to Tuscany and Umbria where they become a new people: The

Etruscans – or the Tyrrhenians as they are called by the Greeks. In the 6th century BC they spread onto the plain of the river Po, and to the south as far as Campania. Their beautiful urban civilization profoundly marks the Italian countryside; the cities have their own water supply, the streets are straight and aligned at right angles, with gutters and extended underground sewage networks, following the Aegean and Oriental traditions. The Etruscan economic miracle rests on three pillars: the mastery of commerce, the exploitation of iron mines, and the development of land for agriculture.

The principal obstacle to development of Etruria is the accumulation of water in the numerous marshy depressions of the valleys. During the entire period from the 7th to the 4th century BC, the Etruscans drain large regions of Italy by means of dense networks of underground drainage galleries, called cuniculi.1 These galleries, from 300 m to several kilometers in length, are about 1.5 m high and 0.5 m wide. They normally follow the courses of the valleys they drain, aligned slightly off the valley centerline (and usually to the right) at a depth of some 30 meters. Vertical shafts are regularly spaced at 30 to 35 m, extending from the galleries up to the surface. These shafts facilitate the initial digging of the drainage galleries, and then provide aeration. These cuniculi follow the valley down to its mouth, or sometimes pass under a ridge to connect to a neighboring valley.

This preoccupation with land drainage is accompanied by a need to control the supply to, and level of, the many lakes of Etruria. Underground drainage works are built in the lakes of Burano, Nemi (near Rome), and Albano. Lake Albano has a 1.5 m wide tunnel that varies in height from 2 to 3 m. It is 1,200 m long, and passes underneath the present city of Castel Gandolfo. There are also artificial reservoirs, excavated and then sealed through paving with a mixture of clay and chalk. These reservoirs are used in the [208] wet season to store water, and in the dry season to supply water for crops through terracotta pipelines.[209]

In their conception and construction of underground conduits, the Etruscans show a marvelous mastery and skill in hydraulic works. They are also good miners. Their know-how in both areas could well have been developed locally, but they surely brought much of their expertise in hydraulics from the Orient. It is interesting to note certain similarities between the Etruscan cuniculi and the qanat, broadly spread within the Persian Empire for water supply (see Chapter 2, Figure 2.19). Recall too that the Mycenaeans used natural grottos to drain marshy depressions (see Chapter 4, in particular Figure 4.10).

The Etruscans are not only miners and peasants, but also sailors: they give their name to the Tyrrhenian Sea. In the 6th century BC, they share maritime domination of the western Mediterranean with the Carthagenians. Their united forces defeat the Phoenicians of Massilia (Marseilles) at the naval battle of Aleria (in Corsica), in about 535 BC. Maritime commerce flourishes, and numerous ports are developed. But in 474 BC, the Syracuse fleet defeats the Etruscans, pushing their maritime commerce back toward the Adriatic. The large port of Spina on the Adriatic is built on a lagoon that is connected to the sea, some 3 km distant, by a 30-m wide canal. It is likely that this port resembled modern Venice, with its canals connecting to the sea and to the nearby estuary of the Po.[210]

Simple huts occupy the site of the seven hills of Rome From the 8th century BC, around the marshy depression where the forum will later be built. This site, at the southern boundary of Etruria, is easily fortified, and the Tiber River, navigable by small boats, adds to the attractiveness of the site. It is here that one finds the first ford of the Tiber, and soon the first bridge, that of Sublicius. In 575 BC, a city is founded here by Tarquin (Tarquin the Elder), a rich Etruscan.

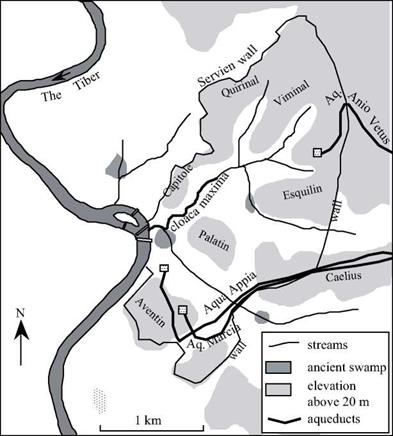

Quite logically, the first hydraulic project in the city is a drainage canal (Figure 6.1). Tarquin the Elder constructed the cloaca maxima to drain the depression of the forum and reclaim its land. At the end of the 6th century BC, Tarquin the Superb, third and last of the Etruscan kings of Rome, had the cloaca Maxima covered over since its physical presence had become an obstacle to further development of the city. With this, the canal began to also serve as a sewer. It had been generously dimensioned by its initial builders, and was not further modified until the 1st century BC under Augustus. Pliny the Elder left us a few words describing this work:

“(…) there are seven rivers, made, by artificial channels, to flow beneath the city. Rushing onward, like so many impetuous torrents, they are compelled to carry off and sweep away all the sewerage; and swollen as they are by the vast accession of the pluvial waters, they reverberate against the sides and bottom of their channels. Occasionally, too, the Tiber, overflowing, is thrown backward in its course, and discharges itself by these outlets: obstinate is the contest that ensues within between the meeting tides, but so firm and solid is the masonry, that it is enabled to offer an effectual resistance.”[211]

|

Figure 6.1 The city of Rome under the Republic, the cloaca maxima, and the arrival into the city of the first aqueducts. The Aqua Applia passes underneath the Aventin. The Marcia, carried on arches in the countryside, is at a higher elevation, and arrives at Aventin through the siphon of Caelius. |

Rome became a republic in about 509 BC, Tarquin having been run out. After the incursion of the Gaels into Italy, about 390 BC, Rome becomes the main power of central Italy. The Aqua Appia, first of the Roman aqueducts, is built in 312 BC. Its dimensions are similar to those of the Etruscan cuniculi (0.69 m by 1.69 m), and almost all of it is buried:

“For 441 years after the founding of Rome, the Romans made do with water that they drew from the Tiber, from wells, or springs. The memory of the springs is still a fond one today. (….) Under the consulship of M. Valerius Maximus and of Pl. Decius Mus, thirty years after the start of the Samnite war, the Aqua Appia was brought into the city by the censor Appius Claudius Crassus, later known as Caecus (The Blind). He is the one who also established the Appian Way from the Capene Gate to the city of Capua. (….). The Appia is fed from a location in a domain of Lucullus, on the Praenestina road, between the seventh and eighth milles. (…). From the saline spring, a named place near the Porta Trigemina, the conduit has a length of 11,190 paces, of which 11,130 are an underground canal, and, above ground, on supporting walls and arcades, 60 paces near the Capene Gate.”[212]

Leave a reply