Hydraulics and The Birth of Civilization

Water and the infrastructure for its conveyance are ever-present needs of civilization, whether for irrigation or flood protection, for water supply or for wastewater drainage from the earliest cities. Added to these needs are those of waterborne commerce, canals, and ports.

This story begins in the East with the great Neolithic revolution, humanity’s fundamental stride into an economic system of production, of agriculture and its accompanying development of the first cities.

In the near-East there is a zone of hills called the “fertile crescent” extending from Syria-Palestine to the foot of Mounts Taurus and Zagros. On these hills, blessed by ample rainfall, naturally grow wild grains such as barley and wheat. The natural fertility of this zone began to develop around 16000 BC, when the climate began to become warmer and moister. This occurred first in the western portions of the area where, after the interruption of a dry and cool period from 10500 to 9000 BC, the climate stabilized to become more or less as it is today, albeit somewhat more humid.1 The change continued into the eastern portions of the zone, in the foothills of Mount Zagros in present-day Iraq, and finally ended about 7000 BC with the permanent inundation of the Persian Gulf.

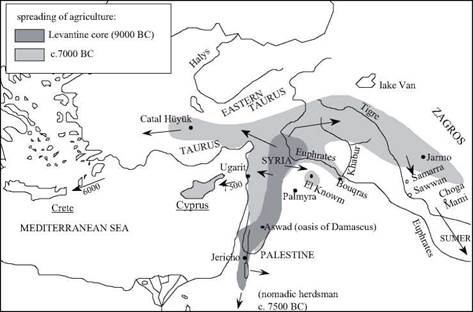

In about 12500 BC, in this fertile land in the middle and to the west of the present fertile crescent, the harvesting of wild grains led the hunter-gatherers to begin to settle. Toward 9500 BC they began to take charge of their means of subsistence. They came down from the hills to begin early cultivation of domestic grains and cereals in the sedimentary corridor from the Jordan Valley to the upper valley of the Euphrates, and in the oasis of Damas. For example, in the IXth millennium BC, Jericho is a village located near a spring; a rather large settlement of two hectares and probably having several hundred inhabitants, surrounded by a thick wall possibly designed to protect the inhabitants from floods. Prehistorians call this corridor the Levantine core (Figure 1.1).[1] [2]

Subsequently, about 8000 BC, this seat of early agriculture moved north to take root in the Syrian interior and in the south of Anadolu. This is when animal husbandry first appeared, as well as the rectangular dwelling, a major architectural innovation

(prior to this, the semi-underground huts were round). The population began to increase, and this in effect marked the beginning of the Neolithic revolution which occurred from about 7500 BC to 4500 BC. [3] Toward the west, this movement gradually reached the Syrian coast, then the West through two parallel paths: the

Mediterranean and the Danube. The population spread also extended toward the east, and it is this eastern spread that interests us here. The Neolithic human tide reaches the Zagros mountains, where it has now become possible for men to live. Indeed, since 7000 BC the Persian Gulf had been flooded, and was even deeper than it is today.

The human tide spreads into some hospitable niches of the arid Syrian desert: the oases of the regions of Palmyra and El-Kown, and the site of Bouqras, at the confluence of the Euphrates and the Khabur.

|

Figure 1.1 From the Neolithic revolution in the East to the first irrigation canals: birth and spreading of agriculture from the Levantine core toward the culture of Samarra and the land of Sumer, from 9000 to 6000 BC. |

The rain and natural runoff are at first sufficient to provide enough water for grains and vegetables. Then, the needs of individual, isolated farmers or perhaps small groups of them, led to the advent of irrigation through small ditches. This made it possible to improve yields and cultivate new land that lacked sufficient rainfall. It is very difficult to date these very first and rudimentary “hydraulic works”. It is possible that when settlers began to occupy the oases mentioned above, as at Bouqras where, between 7400 BC and 6800 BC, the flood plain of the Euphrates valley was cultivated,[4] or at El-Kowm where, in the first half of the Vth millennium BC, artesian springs were available, some management of water was already occurring. Moreover, the earliest evidence of drainage of water from dwellings was found at El Kowm (Figure 1.4).[5]

The first definite evidence of irrigation dates from the VIIth millennium BC – in the middle Tigris valley, at the foot of the Zagros mountains, and at the sites known as the Samarran civilization (Samarra, Sawwan, Choga Mami). At Choga Mami, remains of what are thought to be two-meter wide canals have been found, canals that connect to the rivers and follow elevation contours for hundreds of meters before distributing the spring flood waters into the fields.[6] The first wells appeared in the VIth millennium BC.

Also in the VIth millennium BC, the irrigated cereal-growing know-how began to spread to the Euphrates delta, a potentially fertile area thanks to its silt deposits, but an arid one. This is the Ubaid culture that may have been the inheritor of the Samarran culture. The multiple channels of the delta surely facilitated irrigated farming in this semimarshy alluvial region. The first great urban civilizations, as we recognize them today, took root here.

Leave a reply