From Mesopotamia to the Syrian Shore: The land of the water pioneers

The triangle of land framed by the Tigris and Euphrates delta, Armenia, and the Syrian coast saw the development of the earliest large-scale techniques for water exploitation. From the IVth millennium BC through the conquest by Alexander the Great (in 331 AD), truly exceptional development occurred in this area.

The most important Sumerian city-states of lower Mesopotamia were Uruk and Larsa to the west; Umma, Lagash, and Girsu to the east; the large port of Ur to the south, and Nippur to the north. These cities imported wood and metals as raw material. The source was Bahrein (Dilmun) in the Persian Gulf, to which the following IIIrd millennium BC text attests :

”Ur Nanshe, the king of Lagash (…) dug a canal ( …) so that Nanshe could bring water into

the canal. Boats from Dilmun, that far-distant country, brought wood to him.”1

But these cities also traded with the upper valley of the Euphrates and Syria, and from this trade arose new cities on the Euphrates, like Habuba Kebira in the IVth millennium BC, then Mari from the IIIrd millennium BC, as well as a veritable explosion of Syrian cities like Ebla, Aleppo, and Qatna.

The first political unification in this vast area from the Persian Gulf to the Syrian coast was achieved by Sargon of Akkad in the Kish region. But his successors (2340 to 2200 BC) found it difficult to maintain this union. The fall of this first Empire ushered in a new era of autonomy of the Sumerian principalities, including the grand kingdoms of Lagash, Ur, and then Larsa and Mari under Semitic dynasties. Later came the establishment of the first empire of Babylon, which more or less included the domain of the conquests of Sargon of Akkad (1792 to 1594 BC).

A troubled period in the middle east began in the middle of the IInd millennium BC. This period saw competition among three great powers for Syria-Palestine: the Assyrian kingdom, the grand Hittite kingdom centered in Anatolia, and Egypt. At this time there was also rivalry for the plains of lower Mesoptotamia among the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Elamites.

Major migrations marked the transition from the Bronze to the Iron Age, around 1200 BC. In the near east, the Sea People (perhaps the Aegeans, themselves chased out by newcomers) left almost all the cities near the coast in ashes, and ended the Hittite Empire. Only Egypt, thanks to its power, successfully repulsed them. This troubled period does not end until the arrival of the Arameans from Arabia. They established a kingdom centered in Damascus about 1100 BC. Somewhat later, in about 1000 BC, David took Jerusalem from the Canaanites.

The great empires of Assyria, and then of Persia under the Achaemenids, were built on the ruins of this tumultuous period in the Ist millennium BC. The Assyrian Empire [34] reached its pinnacle between 890 and 606 BC, a period of delicate stability given the powerful rival Urartu to the north (Armenia), the revolts of Babylon, and the rise of the power of the Medes to the east. Assyria even extended its domination into Egypt, but only for a brief period. With the fall of the Assyrian Empire, Babylon again came to the forefront of the political scene in Mesopotamia, but not for long (604 to 539 BC). This period ends when the Persian, Cyrus the Great, and Cambyse, his successor, conquer the entire region, including Syria-Palestine, Anatolia, Egypt, and even Bactria.

|

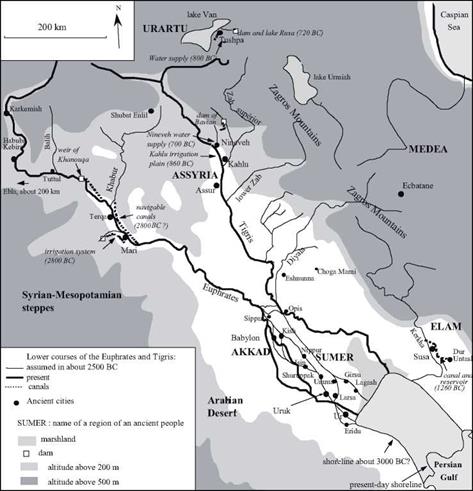

Figure 2.1 Principal sites of ancient Mesopotamia; overview of the major hydraulic works. |

This region is topographically unbounded, without natural limits or constraints. Civilizations came and went, but all of them depended on the efficacy of the irrigation systems inherited from their predecessors. Hydraulic technology, including the first great canals and dams, are passed from one civilization to another and spread outwards from the region. Let us first look at the great alluvial plain of lower Mesopotamia, the ancient land of Sumer and of Akkad.

|

Figure 2.2 The Euphrates valley and the irrigated plain upstream of Mari – looking downstream from the cliffs of Doura-Europos (photo by the author). |

Leave a reply