Drainage and land improvement in the Mycenaen civilization

Many of the regions of Peloponnese or Attica are karsitic. Entire rivers disappear into abysses or caverns (called catavothres in Greek), only to reappear at some distant point.

When the subterranean cavities fill up or are blocked, for example after earthquakes, water can accumulate in marshes and lakes, the water level varying from season to season and from one period to the next. Strabo describes these phenomena:

“Some of these plains are marshy, since rivers spread out over them, though other rivers fall into them and later find a way out; other plains are dried up, and on account of their fertility are tilled in all kinds of ways. But since the depths of the earth are full of caverns and holes, it has often happened that violent earthquakes have blocked up some of the passages, and also opened up others, some up to the surface of the earth and others through underground channels. The result for the waters, therefore, is that some of the streams flow through underground channels, whereas others flow on the surface of the earth, thus forming lakes and rivers. And when the channels in the depths of the earth are stopped up, it comes to pass that the lakes expand as far as the inhabited places, so that they swallow up both cities and districts, and that when the same channels, or others, are opened up, these cities and districts are uncovered; and that the same regions at one time are traversed in boats and at another on foot, and the same cities at one time are situated on the lake and at another far away from it.”[151]

To be arable, these valleys had to be drained and the lake levels stabilized. The most important of such efforts were developed in Beotia by the Mynians (subjects of the king Mynias), near Orchomenos, their capital. The memory of Mynian power and management of the lake Copais was still fresh at the time of Strabo:

“They say that the place now occupied by lake Copais used to be dry, that it then belonged to the Orochomenians, their close neighbors, and that all sorts of crops were grown there. Here one sees an additional confirmation of the wealth of this city.”[152]

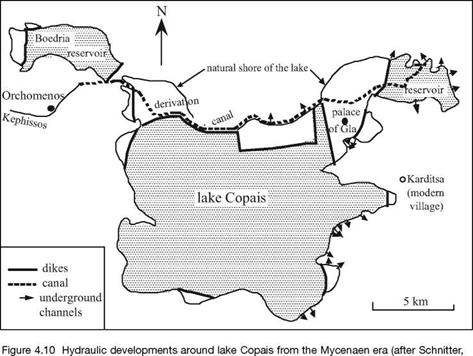

Lake Copais is fed by runoff from rainfall and by the Kephissos river. The natural grottos already mentioned, i. e. catavothres, were used to drain it to the sea.[153] The waters of the Kephissos, previously flowing into the lake, were detoured to an underground passage through a 25-km long canal. The canal may have also been used for navigation. The land reclaimed by emptying of the lake was itself drained, surrounded by protective dikes, and brought under cultivation. Water from what remained of the lake provided irrigation for these lands. The Mynians built the palace of Gla (Homer’s Arne) in one area reclaimed from the lake, in the middle of the depression. The lake, now fed only by runoff from rainfall, was nearly dry in the summer, so that part of its bed could also be cultivated. Figure 4.10 is a map of developments around the lake that were very likely in operation about 1300 BC. With the end of the Mycenaen civilization, the lake’s systems were no longer maintained, and the marshy lake reestablished itself. Between 334 and 331 BC one of Alexander the Great’s engineers, a certain Crates of Chalchis, again set out to drain and dry the lake. But these efforts were not completed, either because of technical difficulties in the region or some other troubles.

|

1994). |

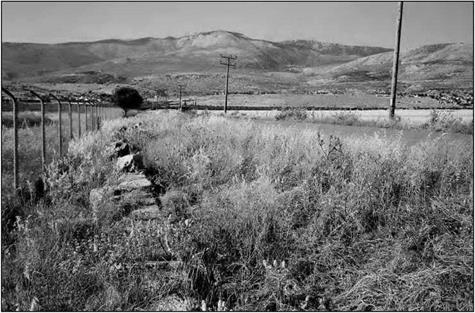

These same techniques are used to reclaim marshy valleys in many other locations. Typically there are dikes surrounding a reservoir-lake fed by rainwater and snowmelt, the dikes also serving to protect dry areas that are drained into grottos or caverns. Eight such reservoirs, including the Boedria reservoir shown in Figure 4.10, are listed in table 4.1. Five of these sites are in Peloponnese (Figure 4.6). For all of these projects, the dikes are between two and four meters high, and of variable length from 200 to 2,500 m. They most often are built of earth fill between two exterior walls. Some of these dikes are still visible today (Figure 4.11).

|

Table 4.1 Mycenaen dam-reservoirs (after Knauss, 1991; Schnitter, 1994)

|

|

Figure 4.11 Remains of the Kineta dam (Thisbe), 1,200 m long. The modern road was built on top of the ancient dam; at the left, remains of the wall of large cut stone (photo by the author). |

Leave a reply