Development of Assyria. The waters of Nineveh

The sovereigns of Assyria begin development of their land on the upper course of

|

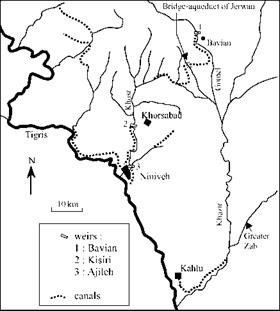

Figure 2.15 Irrigation and water supply works in Assyria in the 9th and 8th centuries BC (after Jacobsen and Lloyd, 1935; Roaf, 1990; Schnitter, 1994; Bagg, 2000)

the Tigris in about 900 BC. This date marks the flowering of an Assyrian Empire destined to reign over all of Mesopotamia, and even as far as Egypt, for about three centuries. In 860 BC, Ashurnasirpal builds a new capital Kahlu (today Nimrud) on the left bank of the Tigris near its confluence with the upper Zab. A canal called babilat nuhshi (“bringer of abundance”) is dug to irrigate the plain with waters of the Zab diverted into the canal by a dam or weir.

It is interesting to note also that a ventilation system comprising chimneys (“air doors”) provides fresh air taken from the roofs of the royal palace to its grand rooms. But it is Sennacherib, the destroyer of Babylon, whom we are now going to see in a different light. He was a lover of gardens. Since Khorsabad, the ephemeral city created by his father Sargon II, was too austere, Sennacherib re-adopts Nineveh as his capital. Taking advantage of his unlimited supply of manpower, he immediately sets out to acquire the water necessary for his horticultural aspirations (Figure 2.15). His first project, in 703 BC, is a 16-km long canal, fed by the Khosr, that brings water to the plain to the west of Nineveh. The waters of this canal, diverted into it by means of an overflow weir at Kisiri, irrigate orchards on plots allocated to the inhabitants of the capital through a lottery system:

. from the environs of Kisiri to the plain of Nineveh, across mountains and valleys, using iron picks, I dug a canal. Along a distance of one beru and a half (16 km) I took water from the river and made it flow down to irrigate the orchards.”[75]

Several years later, the area is in need of even more water. Sennacherib himself sets off into the mountains to see what springs existed. In 694 BC he had water tapped from the springs in the hills northeast of the city and brought to Ajileh, on the Khosr. The remains of two diversion weirs, constructed of large blocks of cut stone, are still visible there. But this new influx of water exacerbated the damaging floods in the Khosr. Therefore the king built a weir downstream of Ajileh to divert floodwaters into a canal going around the city to the south, and thence into artificial lakes. The king had plants and birds brought from the marshes of Babylonia, where he had admired them, to these lakes. The diversion weir was of serpentine shape, having a long crest length of 230 m that thus limited the rise of water during floods. The height of the weir itself was three meters.

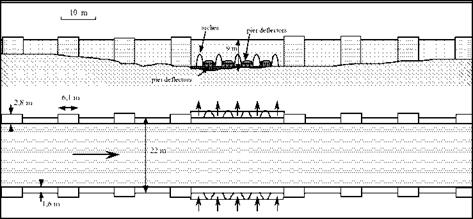

But in the end even this additional water supply was insufficient, so its most spectacular feature was added to finally complete the system in 690 BC. Water was diverted from the Gomel, a tributary of the Zab to the north, and brought to the Khosr through a 55-km lined canal-aqueduct formed of lateral walls of cut stone crossing valleys on arches. At Jerwan (Figure 2.17) one can still see the remains of a magnificent bridge – aqueduct 275 m in length and 22m wide, crossing a valley by means of five arches each 4.75 m high. The diversion works on the Gomel at Bavian apparently included an oblique weir across the river. The canal, 6 m wide at its origin, passes through a short tunnel to cross a rocky spur.

Above the intake there are inscriptions that praise the hydraulic works of Sennacherib.[76] These inscriptions also describe an incident that occurred during the inauguration of the project, an incident that would surely have been very unfortunate for the engineers had the king not been in a good mood. The water pressure caused the closed gates to fail before they had been opened, allowing water to surge into the canal:

|

Figure 2.17 A central portion of the bridge-aqueduct of Sennacherib at Jerwan. It is made of essentially cubical 50-cm stone blocks, and is inscribed with the following text: “Thus says Sennacherib, king of the world, king of Assyria: over a great distance, bringing waters (…) of the river called Pulpullia (…), and from springs here and there along its course, I dug a canal to the edge of Nineveh. Across steep ravines, I threw a bridge of white stone blocks. And these waters, I made them cross over on this bridge.” (sketch and citation from Jacobsen and Lloyd, 1935). |

“To inaugurate the canal, I summoned the priests (…) and made offerings of lapis lazuli (a semiprecious stone), precious stones and gold to Ea, god of springs, fountains, and prairies, and to Enbilulu, god of rivers. I prayed to the great gods, and they heard my prayer. The gate yielded and let water enter in abundance. Even though the engineers had not opened the gate, the gods assured that the water found its way. After having inspected the canal and put things back in order, I offered sacrifices to the great gods (….) To the men who had dug the canal, I offered white linen cloth and colored woolens; I decorated them with rings and daggers of gold.”

This system is perhaps the first example of cross-basin water transfer.

It is also likely during the era of the Assyrian Empire that irrigation canals were constructed on both banks of the Khabur, nearly continuously along the length of the river.

Leave a reply