Brief history of the Hellenistic kingdoms and their successors1

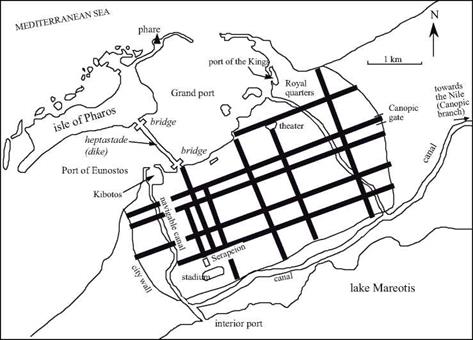

Setting out from Macedonia, with contingents of Macedonian and Greek soldiers, Alexander achieved a first victory over the Achaemenid King Darius II, who ruled the Persian Empire, at the battle of Issus. Egypt falls without resistance into the clutches of Alexander, who makes a long sojourn there from 332-331 BC. During this sojourn, he founds Alexandria on the seafront, an ideal site for the development of commerce, lying [163] between the sea and a lagoon. But the site is poorly supplied with fresh water, being some distance from the Nile. Considerable engineering efforts are undertaken to support the burgeoning activity of the city (Figure 5.2). These include a kilometer-long dike (hepstastade) to link the island of Pharos to the coast, a 30-km canal to bring fresh water from the Nile, and numerous cisterns to store this water. Later a lighthouse is built to guide maritime navigators along this low-lying and dangerous coast. [164]

|

Figure 5.2 The city of Alexandria and the harbor works described by Strabo who visited it around 25 AD. “The point of the island is a rock assailed by the waves on all sides and supporting a tower made of white stone, admirably constructed, having several levels, and having the same name as the island. Sostrate of Cnide, a friend of the king’s, dedicated it as a salute to navigators, as shown on its inscription. [….] The opening to the West [.] forms a second port, that of Eunostos, which sits opposite the closed and artificial port. The port whose entry is next to the tower of Pharos, mentioned above, is the major harbor; two others are contiguous to it at the back of the bay, separated from the main port by the Heptastade dike. The dike forms a kind of bridge […] with two open passages. [….] This dike actually served as both a bridge and an aqueduct, during the period when Pharos was inhabited. […] The city has many advantages. First, the location touches two seas, to the north the Egyptian sea, as it is called, and to the south by the Mareia Lake, also called lake Mareotis. This lake is fed on its upper boundary and sides by numerous canals coming from the Nile. […]. When leaving by the Canopic gate, one sees to the right the Canal, which connects the Lake and Canope.” (Geography, XVII, 1 6-7 and 16).2 |

Leaving Alexandria, the conqueror succeeds in completely destroying the Persian Empire through a decisive victory, and pushes on to the Indus. He dies an early death at Babylon in 323 BC, before having solidified his Empire. Indeed, his generals divide up – and fight over – the elements of that Empire. The Macedonian Ptolemy, son of Lagos, founds the dynasty of the Lagides in Egypt. Lysimachus receives Thrace. Seleucos obtains Babylonia several years later, and then Syria. But his family line, the Seleucids, only intermittently govern lower Mesopotamia, as it is fought over by other powers such as the Parthes, who progressively push the Seleucids toward Syria. New kingdoms of Hellinistic culture appear to the north of the empire of the Seleucids, along the Black Sea: Pontus, Bithynia, and Cappadocia. The power of the city of Pergamon, initially just a simple fortress, increases in Asia Minor and it becomes a dependency of the Seleucids from about 282 to 260 BC, capital of an increasingly powerful empire. From 260 BC, the influence of Pergamon becomes comparable to that of Alexandria.

The Seleucids are conquered by the Romans, allied with Pergamon, in 189 BC. In 133 BC the last king of Pergamon bequeaths his kingdom to Rome. From the middle of the 2nd century BC, a certain decadence of the Lagide Dynasty sets in, including economic difficulties and revolts. With the death of Cleopatra, in 31 BC, Egypt in its turn falls under the control of the Roman Empire.

Leave a reply