Between the Middle Euphrates and the Syrian coast: dams and canals from the IVth to the IInd millennium BC

The site of Jawa, a hundred kilometers to the northeast of Amman in Jordan, is an enigma. It is an arid zone, in a desert of rough black basalt. The only source of water, apart from very infrequent rains, is the winter flood of a seasonal watercourse that comes down from Djebel Druze, the wadi Rajil. The site is somewhat off the track of communication routes, but on the other hand it is easily defendable. Jawa had some 2,000 to

3,0 inhabitants toward the middle or the end of the IVth millennium BC. In this region [50] [51] where there had never been any settlements before, and where there will not be any new ones for several hundred centuries to come, these people built a fortified walled city, a citadel in essence. A British expedition, led by Svend Helms, explored the site between 1973 and 1976, and postulated that these people were refugees or migrants from some urban culture.[52]

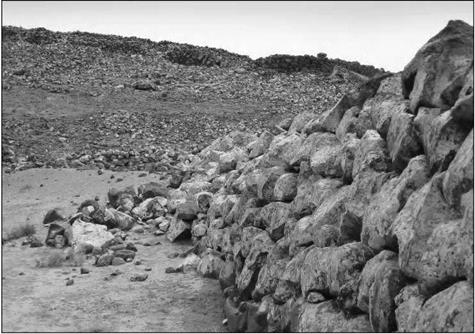

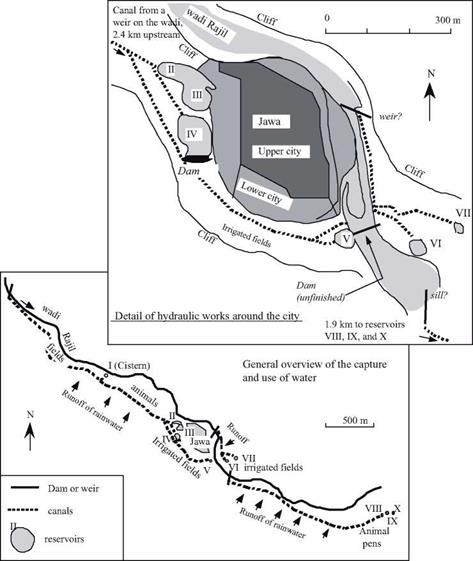

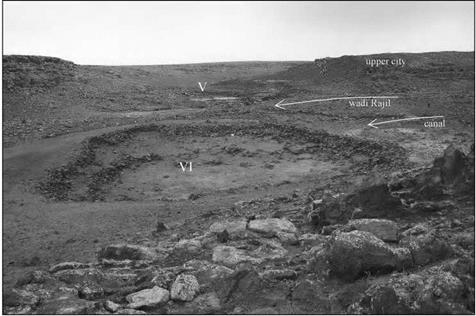

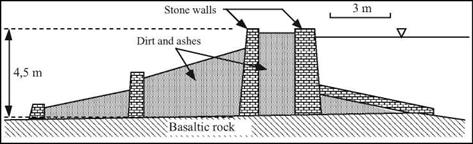

For their water supply, the inhabitants of Jawa built an elaborate system that fills reservoirs with the runoff of winter and spring rains, and also with water diverted from the wadi Rajil during the floods of November and May. Three weirs on the wadi Rajil divert water into stone-lined canals that are several kilometers long and convey flow to ten reservoirs (Figure 2.6). Some fifteen gates control the capture and distribution of water toward either the multiple reservoirs, or toward irrigated fields. Three of the reservoirs (Nos. II to IV, with a total volume of 42,000 m3) supply the city itself. Several other smaller reservoirs, totaling some 10,000 m3, supply animal pens. Cistern No. I, upstream of the city, is dug into a cavity of basalt. Open-air reservoirs Nos. VII, IX, and X are downstream of the city. One of the reservoirs (No. IV on the figure) is formed by a true dam, 4.5 m high and 80 m long. The dam comprises two stone walls confining a central impermeable earth core that is two meters thick (Figure 2.7). A hydrologic study has shown that the storage of water from the two combined sources (rainfall plus floodwaters of the wadi) could supply 3,000 to 5,000 inhabitants and their animals for an entire year.[53] The people of Jawa had even begun to raise the dam to a height of 5.5 m, and to build another similar reservoir along the course of the wadi Rajil itself. But these projects were destined to remain unfinished, as the city was abandoned after only fifty years of existence. The nature of the catastrophe that led these people to return to their desert wandering remains unknown to this day.

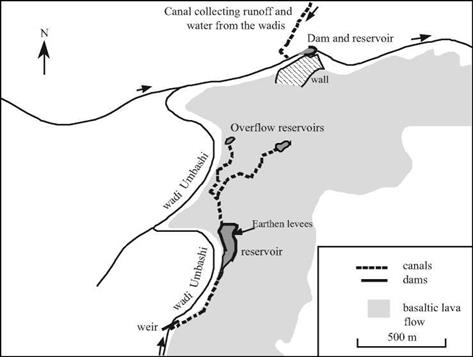

The hydraulic know-how seen at Jawa is not an isolated example. Somewhat later, around 3000 BC, semi-nomadic shepherds settle at the foot of the same mountain, 80 km to the north. Although they are not former city-dwellers like their earlier neighbors at Jawa, these shepherds are driven by the same preoccupation with their security, since they build a wall around their encampment. And like the inhabitants of Jawa, as soon as they arrive they master the same hydraulic techniques. Here, at Khirbet el-Umbashi (Figure 2.8), they form a reservoir in the bed of the wadi itself by building a dam right to the foot of the city wall. This earth dam, 30 – 40 m long, is later raised (as at Jawa) to reach a height of 6 to 8 meters. This reservoir then stores water brought from the two wadis to the north through a three-kilometer canal, as well as water from other direct runoff. An oblique weir, two kilometers upstream on the wadi Umbashi, diverts water toward another very large reservoir (some 30,000 m3) developed in a natural depression bounded by massive levees that attain heights of 2 to 3 m and a base width of 25 m.

|

Figure 2.6 The hydraulic system of Jawa – end of the IVth millennium BC (after Svend Helms, 1987). |

|

|

|

|

Figure 2.7 The dam for reservoir No. IV at Jawa; the oldest known dam (Helms, 1987b). Vogel (1991) gives a similar but slightly different reconstitution of this dam, with only two stone walls (the major ones), a downstream earthfill slope of 0.4 : 1, and a thinner upstream rock drainage layer. |

|

Figure 2.8 The hydraulic system of Khirbet el Umbashi – about 3000 BC – after Braemer, Echallier, and Taraqji (1996) |

At a neighboring site, Hebariyeh (in today’s Lebanon) one again finds the same kind of development, with a large watertight reservoir fed by diversions along a wadi and canals several kilometers in length. Unlike the ephemeral urban establishment of Jawa, these last two sites survive until about 1500 BC.[54] One can find additional remains of canals that collect rainfall along hundreds of meters of length[55] at other sites more to the west along the shores of the Dead Sea, from the beginning of the IIIrd millennium BC.

These hydraulic works represent the oldest known dams. It is impossible for them to represent merely local and isolated inventions. How could the new settlers at Jawa or at Khirbet el Umbashi have known how to construct, then and there, such relatively highly evolved hydraulic systems without having known of similar projects before? Therefore it seems clear that the construction of weirs and dam-reservoirs on intermittent watercourses had already become a technique known throughout the region from the end of the IVth millennium BC. The oasis of Damascus, occupied from Neolithic times, could have been at the origin of these techniques – though nothing is known of it during the period that interests us here. It should be remembered as well that the middle of the IVth millennium BC is a period of expansion of the Sumerian civilization. Habuba Kebira, with its highly perfected sewers, arises on the Middle Euphrates around 3500 BC, then is abandoned at some later date that could be close to the time of the founding of Jawa. With the beginning of the IIIrd millennium BC comes the period of the founding of Mari.

Leave a reply