A dam to protect Tiryns

A catastrophe strikes the city of Tiryns toward the end of the Mycenaen civilization. The city is located on an alluvial plain about one kilometer from the sea; the palace is 24 m above sea level, on a limestone hill. The city itself is at the foot of the palace, to the east and south. The watercourse along which the city is located, the Lakissa, leaves the mountains on a steep slope of nearly 15 m/km as dictated by the local topography.

Levees normally protect the city from the caprices of the river. But in about 1200 BC, at essentially the same time that the nearby city of Mycenae and its palaces were destroyed and burned, an exceptional event occurred. The Lakissa River left its bed, flowed to the north across the lower city, and covered most of the city with a thick layer of sediments, as much as 4 m deep in places. Only the palace on its hill in the southern part of the city was spared the effects of the deluge. This event could have been caused simply by an exceptional flood, or more likely by a major earthquake, the same one that destroyed Mycenae. Such a quake could have caused the collapse of the riverbanks causing a wave of debris-laden water rushing down the steep slope of the riverbed.[154]

|

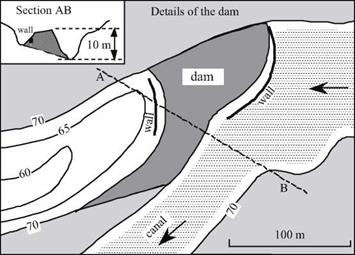

But this event did not mark the end of the Mycenaens. To protect the city from the Lakissa, they built a dam 3.5 km upstream to divert waters of the Lakissa into a 1.5 km canal for conveyance to another watercourse, the Manessi, that flows more to the south (Figures 4.12, 4.13 and 4.14). This 10-m high dam, extending 57 m and 103 m across the left and right banks, respectively, is built of earth fill between two walls of the same type of cyclopean masonry[155] that is used in other Mycenaen works. The lower city is rebuilt on top of the sediments that buried the old city, eventually occupying about the same overall area as before (see inset in Figure 4.12).

|

|

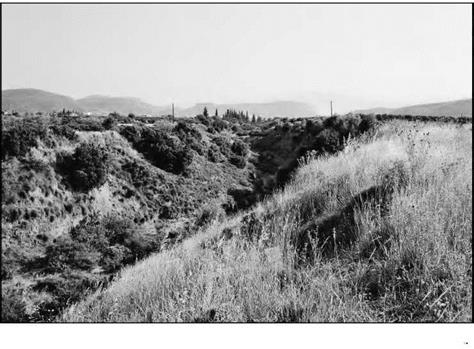

Figure 4.14 Lakissa diversion canal, looking from the top of the Kofini dam (photo by the author)

Figure 4.14 Lakissa diversion canal, looking from the top of the Kofini dam (photo by the author)

This account illustrates the kinds of natural catastrophes that, in the troubled climate of the years around 1200 BC, may have contributed as much to the destruction of the palaces as did the Dorian invaders. Nonetheless, the Mycenaen civilization was still strong enough to implement the hydraulic works that returned the city of Tiryns to safety. A century later this civilization of Nestor, Menelaus and Agamemnon, warrior-

builder descendents of the Minoans, does finally succumb to the overwhelming pressure of the Dorians, leaving only legends behind.

Leave a reply