Compression and Tension in Beams

Beam is a good catch-all word to identify a (usually) horizontal timber whose job it is to carry a load across a span. Girders and floor joists are common specific examples, as are lintels over doors and windows. Even though many roof rafters are pitched to some degree, they perform as beams, too, although other thrust considerations come into play.

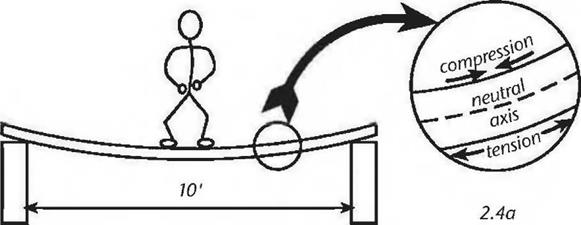

Let’s load a simple but imaginary beam to see how it works. We’ll make it a rather flimsy beam so that its exaggerated performance will show what’s happening. Imagine a 12-foot long two-by-eight plank spanning — flatwise — from one support to another. If the ends of the plank are each bearing on a footwide concrete block, the clear span between supports is ten feet. Now I’ll step on to the center of this “beam,” rather carefully, with my 170-pound weight. Obviously, the plank sags in the middle, and quite a bit. But it probably doesn’t break, even though it has me a little worried. What is happening is that the

underside of the plank is being stretched under my weight; that is, it is in tension. At the same time, the molecules on the top surface of the plank are trying to crush together; it is in compression.

Allowing that this is true — and it is — it follows that an imaginary line along the center of the planks thickness is neither in compression nor tension. This line is known as the centroid or the neutral axis. See Fig. 2.4.

Allowing that this is true — and it is — it follows that an imaginary line along the center of the planks thickness is neither in compression nor tension. This line is known as the centroid or the neutral axis. See Fig. 2.4.

An imaginary beam as here described would be very springy, somewhat like a trampoline. Move one of the supports inward four feet, and we are on the way to

inventing both the cantilever and the diving board. Interestingly, when the beam is cantilevered by placing my weight at its free end, the top surface is now in tension and the bottom surface is in compression.

Instinctively, we know that to lay a “beam” flat like this is — well — stupid. Obviously, if the plank were rotated 90 degrees along its transverse axis — so that it looks like a proper floor joist — it would be very much stronger against bending pressures. It would feel quite stiff to walk along, providing I could maintain my balance for 10 feet. We may think that we know this instinctively, but I submit that it is a matter of our experience more than instinct.

Leave a reply