Building Techniques: Timber Framing for the Rest of Us

|

T |

O THIS POINT, WE HAVE SPOKEN OF CONSIDERATIONS APPROPRIATE for all timber framing projects. But now we have reached a juncture where traditional timber framers go one way and the rest of us take another path. As Yogi Berra said at a college commencement speech, “When you get to that fork in the road take it.” I say, “Let’s start at the bottom and work up.”

Timber framing can be married quite happily to a variety of foundation methods, which, in general, can be characterized under four separate categories: piers, footings, masonry walls, and slab-on-grade.

I. Piers. Piers can also be called pillars, columns or posts, and can be made of wood (such as 75-year ground contact six-by-six timbers or railway ties) or of poured concrete. Concrete piers can be in the form of truncated pyramids, such as my friend Steve Sugar did near Hilo, Hawaii (Fig. 4.1 on page 62 and Fig. 4.18 on page 77) or they can be poured within heavy cardboard tubes called Sona tubes. Whether the piers are wood or concrete, they should extend down to below the code-specified frost line where you are building. In northern New York, this is considered to be four feet. It is also a good idea to distribute the load of the post or pier on a large flat stone, say 12 to 16 inches (30.5 to 40.6 centimeters) square. The top of the pillar should be six to twelve inches (15.2 to 30.5 centimeters) clear of grade to protect any wooden post above it, or the sill plate, from damp. Reinforced concrete columns made with Sona tubes can extend three or four feet above grade, if you want to make use of the crawl space under the building.

While I have nothing against piers made with Sona tubes, my personal view is that the 75-year pressure-treated piers will probably last just as long, are cheaper and easier to install by the inexperienced owner-builder, and if it comes to it, easier to replace.

While I have nothing against piers made with Sona tubes, my personal view is that the 75-year pressure-treated piers will probably last just as long, are cheaper and easier to install by the inexperienced owner-builder, and if it comes to it, easier to replace.

ion today, the footings are installed sheltered space is desired below grade, us to:

2. Footings. Generally made of poured concrete, footings might typically be 12 to 16 inches wide and at least 8 inches (203 millimeters) thick.

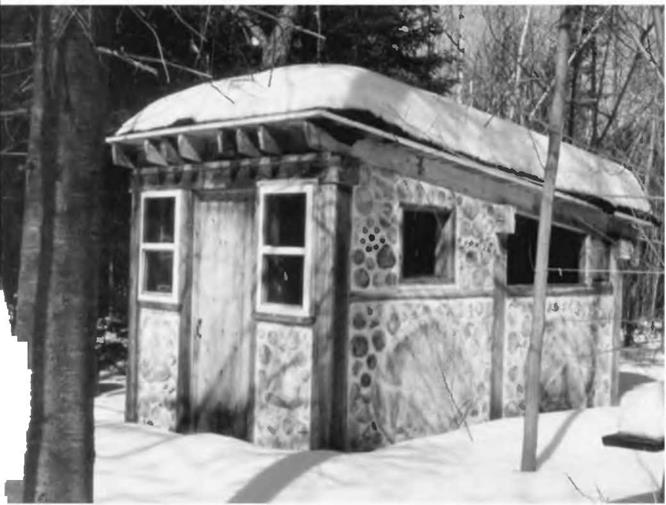

With small buildings, such as a sauna or our little guesthouses, I “float” the footings on a good pad of percolating material. See slab-on-grade below. I call this foundation a “floating ring beam” and its construction is detailed in both my books Complete Book of Cordwood Masonry Housebuilding and The Sauna (see Bibliography). (Fig. 4.2.)

With most northern construct – below frost line, whether an earth – or simply a “crawl space.” This leads

and any intended infilling. For example, if the builder wants a 16-inch-wide cordwood wall, built within a strong post-and – beam frame, the supporting wall (and footings) should also be 16 inches wide. (Fig. 4.3.)

4. Slab-on-grade. This is also known as the “floating slab” or the “Alaskan slab.” It works on the sound principal that frost heaving is caused by water freezing and expanding below the building. The two approaches taken to avoid this problem are (1) to go down below maximum frost depth with the footings or (2) to prevent water from collecting under the foundation in the first place. The second approach is the way the slab-on-grade works. The poured concrete slab “floats” on a pad of percolating material such as coarse sand, gravel, or crushed stone. The pad drains any water to a place further down grade. There is no water under the foundation to freeze, so no nasty uplifting expansion (called “heaving”) takes place. Again, see Complete Book of Cordwood Masonry Housebuilding for a thorough discussion. But, be sure to follow local code, too. The slab-on-grade does appear in the new International Building Code, now used in most states.

4. Slab-on-grade. This is also known as the “floating slab” or the “Alaskan slab.” It works on the sound principal that frost heaving is caused by water freezing and expanding below the building. The two approaches taken to avoid this problem are (1) to go down below maximum frost depth with the footings or (2) to prevent water from collecting under the foundation in the first place. The second approach is the way the slab-on-grade works. The poured concrete slab “floats” on a pad of percolating material such as coarse sand, gravel, or crushed stone. The pad drains any water to a place further down grade. There is no water under the foundation to freeze, so no nasty uplifting expansion (called “heaving”) takes place. Again, see Complete Book of Cordwood Masonry Housebuilding for a thorough discussion. But, be sure to follow local code, too. The slab-on-grade does appear in the new International Building Code, now used in most states.

Incidentally, Frank Lloyd Wright liked both the floating slab and another foundation method, which works on a similar principle, called the rubble trench. By this method, a trench is dug down to just below frost level, and then filled with fairly coarse (potato-sized) stone. Footings are formed and poured on this stone at grade level. The trench is drained to some point down grade, so the method is best suited for a site with sufficient grade differential.

The best discussion of the rubble trench foundation, good enough to build from, appears in the excellent book Foundations and Concrete Work (see Bibliography). Using just the information in that book, Ki Light made his rubble trench foundation. A concrete footing floats on the packed rubble, and his post and beam frame (and his straw bales) are founded on this footing. You’ve already seen Ki’s house in Fig. 1.2.

The present book, though, is about timber framing, not foundation methods. Maybe someday I’ll do a book called Foundations for the Rest of Us, but don’t hold your breath. Almost any good generalized building book (including Foundations and Concrete Work, page 17) will show you how to set up “batter boards” to establish a square foundation. This fine inexpensive book also explains the slab – on-grade and other foundation methods.

Leave a reply