The Method and the Madness

My reasons for choosing to live in such small houses include some environmental concerns. The two largest of my three, hand-built homes were made with only about 4,800 pounds of building materials each, less than 100 pounds of which went to the local landfill. Each produced less than 900 pounds of greenhouse gases during a typical Iowa winter. And, at 89 square feet, plus porch and loft, each fit snugly into a single parking space.

1

In contrast, the average American house consumes about three quarters of an acre of forest and produces about seven tons of construction waste. It emits 18 tons of greenhouse gases annually, and, at more than 2,349 square feet, it would most definitely not fit into a single parking space.

Finances informed my decision, too. Quality over quantity became my mantra. I have never been interested in building anything quite like a standard travel trailer or mobile home. Travel trailers are typically designed for more mobility and less year-round comfort than I like, while most manufactured housing looks too much like manufactured housing for my taste. Common practice in the industry (though not inherent or exclusive to it) is to build fast and cheap, then mask shoddiness with finishes. This strategy has allowed mobile homes to become what advocates call "the most house for your money.” It has, in fact, helped to make manufactured housing one of the most affordable and, thus, most popular forms of housing in the United States today.

This is pretty much the opposite of the strategy I have adopted. I put the money saved on glitz and square footage into insulation, the reinforcement of structural elements, and detailing. At $30,000, Tumbleweed cost about one – sixth as much as the average American home. Only about $15,000 of this total was actually spent as cash on materials. That is less than half of what the average American household spends on furniture alone. The remaining $15,000 is about what I would have paid for labor had I not done it myself.

The cost of materials could have been nearly halved if more standard materials were used. A more frugal decision, for example, would have been to skip the $1,000, custom-built, lancet window and install a $100, factory-built, square one instead. But I was, and I remain, a sucker for beauty.

The total cost was low when you consider I was able to pay it off before I moved in—but not so low when you consider that I sunk over $300 into every square foot. The standard $110 per square foot might seem more reasonable, but I succumbed to the urge to invest some of the money saved on quantity into quality. As a result, my current residence is both one of the cheapest houses around and the most expensive per square foot.

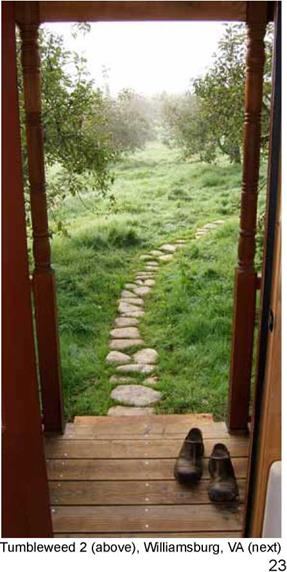

Still, my main reason for living in such a little home is nothing so grandiose as saving the world, nor so pragmatic as saving money. Truth be told, I simply do not have the time or patience for a larger house. I have found that, like

anything else that is superfluous, extra space merely gets in the way of my contentment. I wanted a place that would maintain my serene lifestyle, not a place that I would spend the rest of my life maintaining. I find nothing demanding about Tumbleweed. Everything is within arm’s reach and nothing is in the way—not even space itself.

|

|

Leave a reply