Make the Wind Work for You

Generally, summer and winter winds come from different directions. It’s usually possible to divert winter winds and to channel

summer breezes by carefully locating the house in relation to its surroundings. Check with your local airport, meteorological station, or state energy office to determine the prevailing summer – and winter-wind directions for your area. Also, this data can be obtained from the U. S. Department of Commerce National Climatic Center in Asheville, N. C. (www. ncdc. noaa. gov/oa/climate/ climatedata. html).

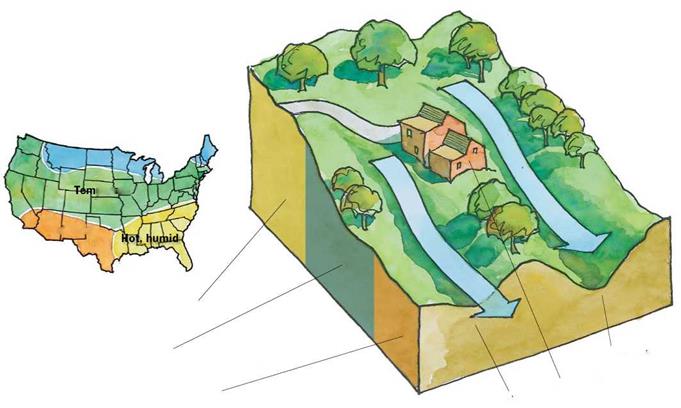

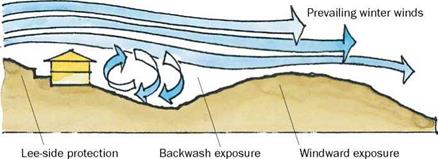

Study the adjacent topography, trees, and buildings during your initial site inspection. Look for those existing conditions that can block or divert cold winter winds around the building site. Locate the house in these lee – side areas (see the top drawing on p. 134).

Study the adjacent topography, trees, and buildings during your initial site inspection. Look for those existing conditions that can block or divert cold winter winds around the building site. Locate the house in these lee – side areas (see the top drawing on p. 134).

In warm or humid climates, place the house in a part of the site that maximizes summer ventilation. For example, the pro

cess of evaporation cools summer breezes as they pass over water bodies. These water bodies don’t have to be big to have an effect. Locate the house to catch prevailing summertime breezes coming off lakes, ponds, rivers, and even streams.

Conversely, in cool and temperate climates, avoid locations near bodies of water on the lee side of prevailing winter winds. In other words, if winter winds generally blow from the north, avoid sites at the south end of a water body.

Water isn’t the only medium that induces cold winter winds. Landforms, vegetation, and buildings all can increase wind velocities because of a phenomenon called the Venturi effect.

|

|

The Venturi effect occurs when any moving medium—in this case air—squeezes

through a constricted opening. To maintain a constant volume of air passing through the opening, the wind velocity increases accordingly. That’s why it’s so windy at the base of tall buildings.

Keep away from topography, adjacent buildings, or vegetation that funnels cold winter winds at increased velocities. If you do have a problem because of the Venturi effect, you can position adjacent outbuildings and evergreen trees and shrubs where they will block winter winds.

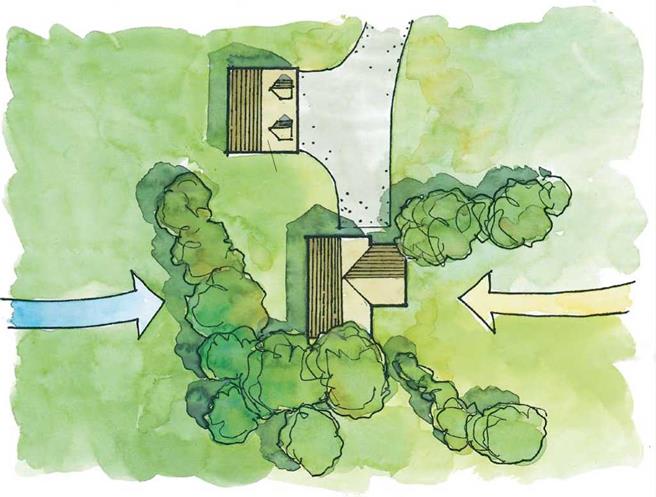

Conversely, locate the house (and any new vegetation, fences, or outbuildings) to take advantage of increased wind velocities created by the Venturi effect during summer months (see the bottom drawing on p. 134). Use buildings and vegetation to channel summertime breezes into the house. As a rule, try to orient the house within 30 degrees of perpendicular to prevailing summer winds to maximize their cooling effects.

If solar orientation and siting for wind are at cross-purposes (that is, if optimum solar orientation is perpendicular to optimum siting for wind), then solar orientation should take precedence because it has a greater cumulative effect on the heating and cooling of a house.

House Shape Should Fit the Climate

Are you familiar with the aluminum heat – radiating fins that can be slipped over hot – water pipes in a basement? They’re supposed to turn hot-water pipes into heating elements to heat the basement space. The principle behind the fins is that they increase the heated surface area so that more heat escapes from the pipe with the fins than from the bare pipe.

The same principle applies to a house’s shape, or configuration. As a house’s surface area increases, so does the amount of heat it loses. To hold on to the heat, configure the house so that it is relatively compact. Compact shapes, such as cubes, lose less heat through the building skin than narrow or elongated shapes.

As a general rule for siting a house in cold regions, the long dimension of the house should be approximately 1.1 to 1.3 times the length of the short side. This proportion yields a high ratio of heated interior space to exterior skin. Remember that the longer side of the house is oriented along the east – west axis.

For temperate climates, the configuration is not as important. There is less environmental stress on the building skin, so the designer has more freedom in terms of building configuration. For this region, a ratio between 1.6:1 and 2.4:1 provides good energy performance.

In hot, arid climates, the environmental stresses are greater, so buildings should be shaped similarly to cold-climate configurations. A ratio somewhere between 1.3:1 and 1.6:1 is the most energy-conserving for hot, arid climates.

In warm or humid climates, elongated shapes with openings on the long sides allow for cross ventilation. Generally, ratios in the range of 1.7:1 to 3.0:1 are preferred. When these elongated plans are oriented with the long side on the east-west axis, summer overheating at the short east and west elevations is avoided.

Try to keep corners on the house to a minimum. Unnecessary corners mean more exterior-wall surface is exposed to wind, which increases heating loads on the house.

Regardless of wind direction and particularly in areas where wind direction changes frequently, a good overall strategy is to use a compact, low-profile house design. Avoid tall facades and roof designs that block or trap wind. For example, a tall, broad gable is less aerodynamic than a hip roof, which allows for smoother airflow around and over the house. Orient the narrowest dimension of the house into prevailing winter winds to minimize wind exposure.

Use plants and outbuildings to direct prevailing summer breezes into the house and to divert prevailing winter winds away from the house. Once you know the direction of prevailing winter winds, choose a site where topography, vegetation, and other buildings offer protection.

Use plants and outbuildings to direct prevailing summer breezes into the house and to divert prevailing winter winds away from the house. Once you know the direction of prevailing winter winds, choose a site where topography, vegetation, and other buildings offer protection.

|

|

|

|

|

Prevailing summer breezes are funneled by deciduous trees into the house at increased velocity due to the Venturi effect.

Configure the house and its surroundings to funnel or channel cooling summer breezes into windows and screened-door openings. For example, you can orient breezeways and window openings to accept these summer winds. Use roof overhangs to

trap incoming breezes and channel them into window openings. On the other hand, locate and configure the house to avoid channeling any cold winter winds into doors and windows.

Leave a reply