HVAC Ducts Can Leak One-Third of the Air They Transport

From 20% to 40% of the air that comes out of furnaces and air conditioners never gets to the rooms it’s supposed to heat or cool. When you consider that most of the ducts are in attics, garages, and vented crawlspaces, the effect of that loss is huge: We’re heating and cooling the outdoors. Sometimes whole rooms are disconnected, as when the ductwork isn’t connected to the register and the duct spews conditioned air into the attic or crawlspace. Return ducts often leak more than supply ducts; although they cause less energy loss, these leaks lead to moisture problems and pressure imbalances that pose health and durability risks by contributing to mold, ice dams, and even carbon – monoxide poisoning.

Required by code, duct-sealing is rarely completed and even more rarely tested. Houses more than 10 years old didn’t have this code requirement. Every connection in every duct run should be sealed with mastic (not tape), and the system should be pressure-tested, just like your plumbing. Holes in the air handler can be sealed with aluminum-foil tape because mastic would render the cabinet unserviceable. After you seal the ducts and the cabinet, insulate them carefully.

Retrofits can be more difficult. If you can access the ducts, you can use mastic under the insulation (put the insulation back when you’re done). If the ducts are inaccessible, they can be sealed from the inside with a product like Aeroseal® (see www. aeroseal .com for local contractors), or you can move the insulation and the air barrier to bring the ducts inside the thermal boundary.

Putting the Air Handler Outside the House Is Not a Good Idea

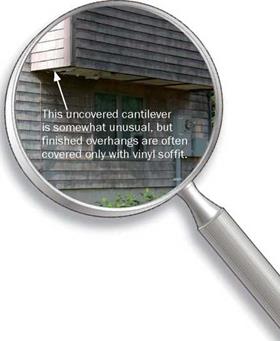

Many air handlers and ducts are in attics. This location is a lot more costly than people realize. Putting an air handler and ductwork in the attic, garage, or crawlspace is like putting it outside the house. In winter, attics are almost as cold as the outdoors; in the summer, attics are much hotter than the outside temperature.

If you must place the air handler and ductwork in the attic, you can do a few things to minimize energy losses: Seal everything with mastic; insulate the air handler carefully; and keep the ducts low and covered with blown insulation. Even better, use spray foam on the whole roof and gable ends so that the attic space is within the house’s thermal envelope.

The best idea, though, is to run the mechanical system inside the house. You can use smaller mechanical equipment with smaller ducts in shorter runs; it’s easier to design space for them within the house. The payoff is a much more efficient HVAC system that increases comfort while decreasing operating costs. For more information, go to www. toolbase. org/Design-Construction- Guides/HVAC/forced-air-system.

How Durable Is Spray Foam?

Q: Spray foam is touted as a “superior” insulation material. I’ve been building for nearly 20 years, however, and I’ve occasionally found spray foam that has settled in the wall cavity and/or disintegrated enough to lose all its effectiveness. How do we know today’s spray foams won’t do the same thing in 30 years?

Q: Spray foam is touted as a “superior” insulation material. I’ve been building for nearly 20 years, however, and I’ve occasionally found spray foam that has settled in the wall cavity and/or disintegrated enough to lose all its effectiveness. How do we know today’s spray foams won’t do the same thing in 30 years?

—Mike Connors, Beacon, N. Y.

A: The failed foam you’re describing is likely urea-formaldehyde foam insulation (UFFI). It was installed in many homes in the 1970s, but eventually was banned in Canada and the United States due to concerns about chemical off-gassing. UFFI also tended to become brittle, shrink, and crumble over time, affecting durability and performance.

The current generation of spray-polyurethane foams is based on a different chemistry, so the cured foam is much more stable. This quality suggests that spray-polyurethane foams will last much longer than UFFI and will retain their flexibility and mechanical integrity.

I wouldn’t worry about the durability of the foams that are currently available. In fact,

I believe that in some applications today’s spray foams add to the durability of the overall structure by reducing air leakage and vapor diffusion.

—Bruce Harley

Leave a reply