Finding the Sweet Spot: Siting a Home for Energy Efficiency

BY M. JOE NUMBERS

|

A |

rchitecture professors love a good riddle. Here’s one: How do ancient Greek town grids, Anasazi Indian pueblos, and New England saltbox houses differ from most residential construction today? Give up? Each culture understood how to site a

house. The ancient Greeks oriented their town grids to receive winter sun and summer shade. The Anasazi Indians located their dwellings beneath cliff overhangs to take advantage of natural shading. Early American settlers oriented and configured their saltbox houses to minimize the cold northern facade and to maximize the warm southern facade.

Regrettably, the siting lore known to our ancestors has practically disappeared because of central-heating and – cooling systems. That’s too bad, because a house’s energy efficiency, comfort, and marketability are all affected by its siting. A house that’s sited to take advantage of the sun, the wind, and the topography costs less to heat and cool, and lets you enjoy indoors and outdoors longer, two strong selling points.

In the site-design classes I used to teach, we divided solar-siting strategies into three categories: orientation, or which way the house faces; location, or where the house sits; and configuration, or how it’s shaped. Figuring out the best orientation, location, and configuration requires a little knowledge of local climatic conditions and an analysis

of the site and its surroundings. Here, I’ll discuss what to look for and where to find the information you need to reap the benefits of a properly sited house.

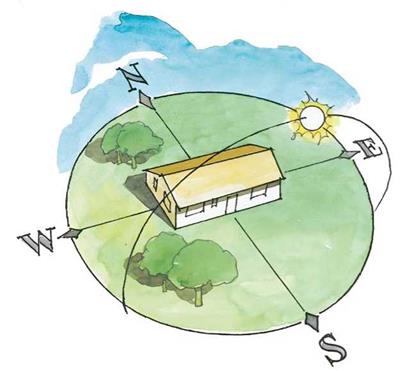

When siting a house, the most effective strategy you can use is to orient the building with the long side aligned on the east-west axis. This orientation places the long side of the building where it can be reached and heated by the low-angle rays of the winter sun. Conversely, it places the short sides of the building to the east and west to minimize solar gains during the overheated periods of summer.

Your house doesn’t have to be exactly on the east-west axis; somewhere within 15 degrees of this axis is fine. What’s more important is that the house is oriented toward true south, not magnetic south. Compass needles point to magnetic north, which deviates from true north by as much as 20 degrees. The difference between magnetic north and true north is declination, and it varies across the United States (see the sidebar on pp. 130-131). Information on declination can be found on U. S. Geological Survey topological maps or the NOAA website (http://www. ngdc. noaa. gov/geomag/ geomag. shtml).

Once you know your area’s declination angle, it’s a matter of spinning the dial on a compass. For example, in Boise, Idaho, the declination angle is approximately 14 degrees east. Line up a compass on magnetic north, then rotate the dial until the needle is pointing to 14 degrees east of the north mark on the dial; now the dial markings (not the needle) point to true north.

Lots of related strategies make a true – south orientation more effective. One is to reduce openings (i. e., windows and doors), especially on the north side of the house, because doors and windows conduct more heat than a well-insulated wall. In cold climates, only about 5% to 10% of non-southfacing walls should be openings. In warmer climates, you can get away with slightly more openings as long as the house is well insulated.

On south elevations, increase openings for winter solar gain, but shade them during summer months. Deciduous trees provide summer shading, as do awnings. You can also build overhangs, but they shouldn’t be so deep that they block the sun in winter (see the drawing on p. 131).

To figure out the optimal depth for overhangs in your area, use the shade-line-factor formula: The depth of an overhang equals the height from the bottom of a window to its overhang divided by the shade-line factor. This number varies with latitude, so you’ll need to know your location’s geographic latitude to choose the right shadeline factor. Most maps of the United States and most state maps show latitude.

Another way to make a southern exposure work harder for you is to coordinate the floor plan with the house’s orientation. Locate public living spaces, such as the living room, the dining room, the kitchen, and such, to the south side of the house, where they will receive light and warmth throughout the year. Locate private and unoccupied rooms—bedrooms, utility rooms, storage rooms, etc.—to the north, where they will act as insulating buffers for the home’s public spaces (see the floor plan on p. 130). These buffer spaces serve as a form of insulation (particularly if they can be closed off

Leave a reply