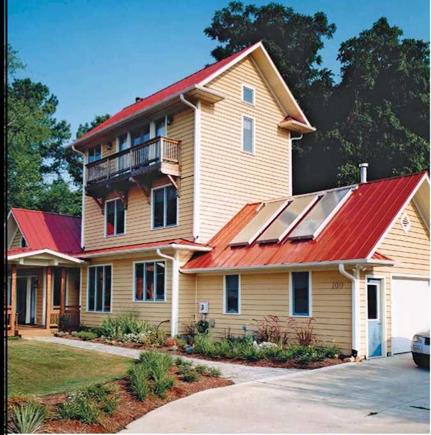

Cool Design for a Comfortable Home

■ BY SOPHIE PIESSE

I live in North Carolina, and I love the look on people’s faces when I tell them that I haven’t turned on my first-floor airconditioning in 10 years. There’s always a pause, and then they lift their jaw off the floor and ask me, "Really? How?"

As an architect who designs new homes, renovations, and additions, I encourage my clients to explore options for passive heating and cooling and energy-smart design before we ever look at mechanically assisted options. To make your house truly energy – efficient, you must design it with the goal of using as little energy as possible. It’s great when people get excited about adding solar hot-water panels and photovoltaic systems, but before exploring any of that, you should first look at how you can design your new home or alter your existing home to reduce its energy needs. When your house naturally needs less energy, you can use smaller mechanical systems to support it. This saves money both up front and in the long run.

Passive Solar vs. Passive Cooling

When we talk about passive-solar design, we often focus on how it can help to heat your home. Passive-cooling design is really the opposite side of the same coin, using the properties of the sun to promote cooling rather than heating.

Passive-solar design can cut heating bills, but in the South and in many areas of the country, keeping your house cool in the summer is a bigger concern. Here, passivecooling strategies become more important, and more economical. These simple design elements can save you hundreds of dollars every year in energy bills and also make your house more comfortable to live in.

Passive cooling refers to nonmechanical ways of cooling your home. It focuses on orientation and shading, air movement, thermal mass, and a tight building envelope. All these strategies can be complemented by mechanical means—from air-conditioning to ceiling fans—but these passive elements can also work successfully on their own.

While the potential for saving energy with any design-focused strategy is greatest when you’re planning a new house, several of the techniques I describe can be used when renovating or adding to an existing home. You may not be able to pick up your house and face it in another direction, but you can add shade structures and window overhangs, relocate window openings, and mitigate nearby "heat islands" (such as a driveway baking in the midday sun), all of which enhance your home’s ability to maintain a comfortable temperature with less mechanical intervention.

So let’s take a look at how your house can work with the environment. By designing your home to work with nature instead of against it, you can benefit from lower energy bills, better daylighting, and greater indoor comfort.

Leave a reply