Air – Conditioning: Bigger Isn’t Better

■ BY CHRIS GREEN

■ BY CHRIS GREEN

|

S |

itting in a green-and-white woven lawn chair, fanning away the sweat, my grandmother said, "It’s not the heat, it’s the humidity." With seven Virginia summers behind me, I suspected that the heat did have something to do with it, but I kept this thought to myself.

It turns out that each of us had it partly right. It was the combination of high heat and humidity that raised us to our exalted level of discomfort on that oppressive summer day.

Seven years later, my parents finally built a house that included central airconditioning. Although it was better than being without, the air-conditioning system wasn’t ideal. The house had cold and hot spots, and my basement bedroom always felt cold and damp.

Unfortunately, these problems weren’t limited to my parents’ house nor to the 1970s. Problematic air-conditioning systems

abound nationwide. According to a recent study, 95% of new air-conditioning installations fail in regard to operating efficiency, with more than 70% of systems improperly sized or installed.

The top three reasons for poor air – conditioner performance are improper sizing (1.5 to 2 times too large is common); improper installation (incorrect refrigerant levels and airflow); and poorly designed and installed duct systems. Because airconditioning systems integrate refrigeration, air distribution, and electronics, there are lots of opportunities for mistakes.

Air Conditioners Move Heat Outside

Heat naturally moves from a higher energy level (warm) to a lower energy level (cool). You could say that heat, like water, flows

Whether it’s new

Whether it’s new

or a replacements properly sized and installed system affords

downhill. Without help, heat that accumulates within a home will not leave on its own unless the heat sources (the sun, people, appliances, etc.) are removed. Help comes in the form of air-conditioning, which uses refrigeration combined with ventilation essentially to push heat uphill, or move it outside, where it’s even warmer.

Residential air-conditioning systems are made up of an indoor and an outdoor unit connected by a pair of pipes that circu

late refrigerant in a loop. By manipulating pressure and temperature, the indoor unit absorbs heat by blowing warm indoor air over a cold coil. The heat is released to the outdoor unit, which houses a compressor (which compresses refrigerant and itself generates heat) and a condenser coil and fan (which dissipates the heat to the outside).

In addition to cooling, air conditioners serve another important function: They dehumidify the air. In the same way that

I How It Works

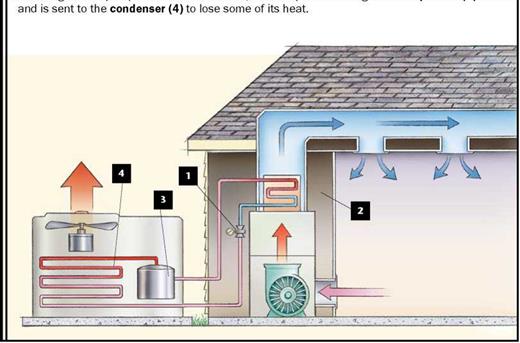

Residential air conditioners are split systems—an indoor and an outdoor unit—that remove heat from the house and release it outdoors. A pair of pipes, which circulate refrigerant, form a loop and connect the units. Cold air is produced when compressed refrigerant is forced through a tiny valve or metering device (1) and expands into the evaporator coil (2), similar to the cold spray an aerosol can produces as the compressed liquid passes through the valve. This causes the refrigerant’s pressure and temperature to drop quickly, cooling the coil.

|

As warm air passes over the evaporator, it is cooled and dehumidified. Moisture condenses on the evaporator’s fins and drains away. After absorbing heat from the home’s interior, the refrigerant is pumped to the outdoor unit, where it passes through the compressor (3)

moisture condenses on the side of a cold soda can sitting outside on a hot day, air conditioners wring moisture from warm, humid air as it is forced across the indoor unit’s cold evaporator coil. Once past the evaporator, cool dehumidified air is delivered to the rest of the house—unless there’s a problem.

Leave a reply