VENTING TOILETS

Because they have the biggest drain and vent pipes of any fixture, toilets can be the trickiest to route vents for. When space beneath a toilet is not a problem, use a setup such as the one shown below, in "Venting a Toilet,” in which a 2-in. vent pipe rises vertically from a 3 by 2 combo, while the 3-in. drain continues on to the house main. The 3-in.-diameter toilet drain, allows the vent to be as far as 6 ft. from the fixture, as indicated in the table on p. 281.

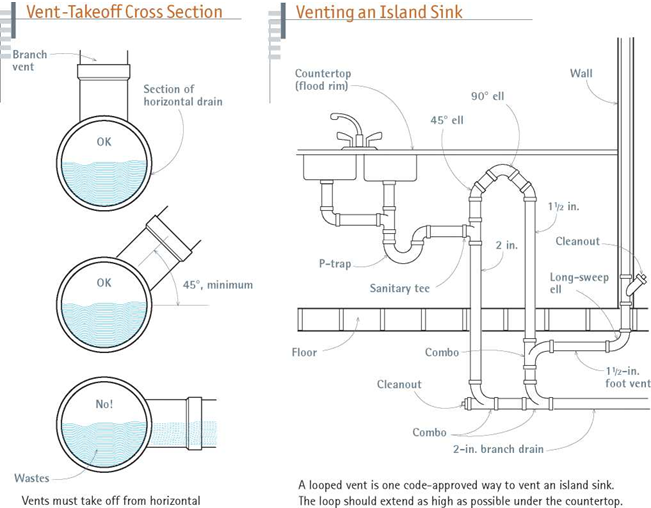

When space is tight, say, on a second-floor bathroom with a finish ceilings below, the drain and vent pipes must descend less abruptly (see "Constricted Spaces,” below. Here, the critical detail is the angle at which the vent leaves the 3 by 2 combo: That vent takeoff must be 45° above a horizontal cross section of the toilet drain. If it is less than that, the outlet might clog with waste and no longer function as a vent. As important, the "horizontal” section of the vent that runs

between the takeoff and the stack must maintain a minimum upward pitch of 1/4 in. per foot.

When you’ve got two toilets back to back, you can save some space by picking up both with a single figure-5 fitting (double combo), like the small one in the bottom photo on p. 277. From the top of the fitting, send up a 2-in. or 3-in. vent; from the two side sockets use two 3-in. soil pipes serving the toilets; and use a long-sweep ell (or a combo) on the bottom, to send wastes on to the main drain. This fitting is about the only way to situate back-to-back water closets and is quite handy when adding a half bath that shares a wall with an existing bathroom.

Common vents are appropriate where fixtures are side by side or back to back. This type of vent usually requires a figure-5 fitting.

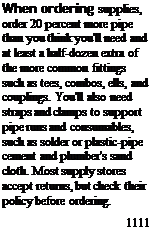

Loop vents are commonly installed beneath an island counter in the middle of a room. The sink

drain is concealed easily enough in the floor platform, but the branch vent, lacking a nearby wall through which it can exit, requires some ingenuity. This problem is solved by the loop shown in "Venting an Island Sink,” below.

In addition to the fittings shown in the drawing, note these factors as well: the loop must rise as high under the counter as possible and at least 6 in. above the juncture of the trap arm and the sanitary tee, to preclude any siphoning of wastewater from the sink. The vent portions may be 1 ’/2-in. pipe, but the drain sections must be 2 in. in diameter, and drain sections must slope downward at least ‘/ in. per foot.

Mechanical vents, also known as air-admittance valves, or pop vents, allow you to use a fixture before the vent runs are complete (say, before you run a vent stack up through the roof). Here’s how they work: As water drains from a sink, it creates a partial vacuum within the pipes, depressing a spring inside the vent and sucking

air in. When the water is almost gone and the vacuum is equalized, the spring extends and pushes its diaphragm up, sealing off outside air once again.

Mechanical vents are temporary vents only.

The UPC allows them only if local jurisdictions permit them—and few do. Because valve mechanisms can wear out and allow septic gases into living spaces, mechanical vents must never be used as permanent vents or in enclosed spaces where they cannot draw air easily.

|

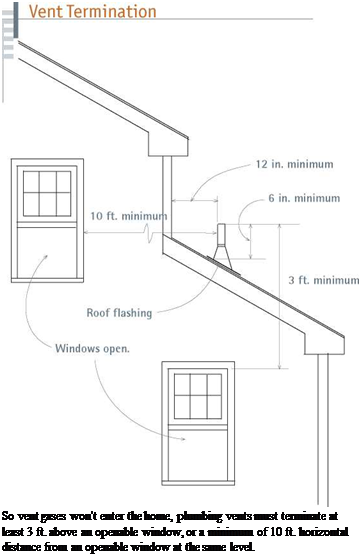

To reduce chances that vent gases will enter the home, stack tops must be at least 6 in. above the upslope side of the roof and at least 3 ft. above any part of a skylight or window that can be opened. A vent stack must at least 12 in. horizontal distance from a parapet wall, dormer sidewalls, and the like. Finally, stacks must be correctly flashed to prevent roof leaks.

![]()

Leave a reply